The Best Public Health Interventions of the 20th Century

Public health interventions in the 20th century have been responsible for massive improvements in global health. According to the Copenhagen Consensus,

“Life expectancy hardly changed before the late 18th century. Yet it is hard to overstate the magnitude of the improvement since 1900, from a life expectancy of 32 years to 69 now, to 76 in 2050. The biggest factor was the fall in infant mortality.”[1]

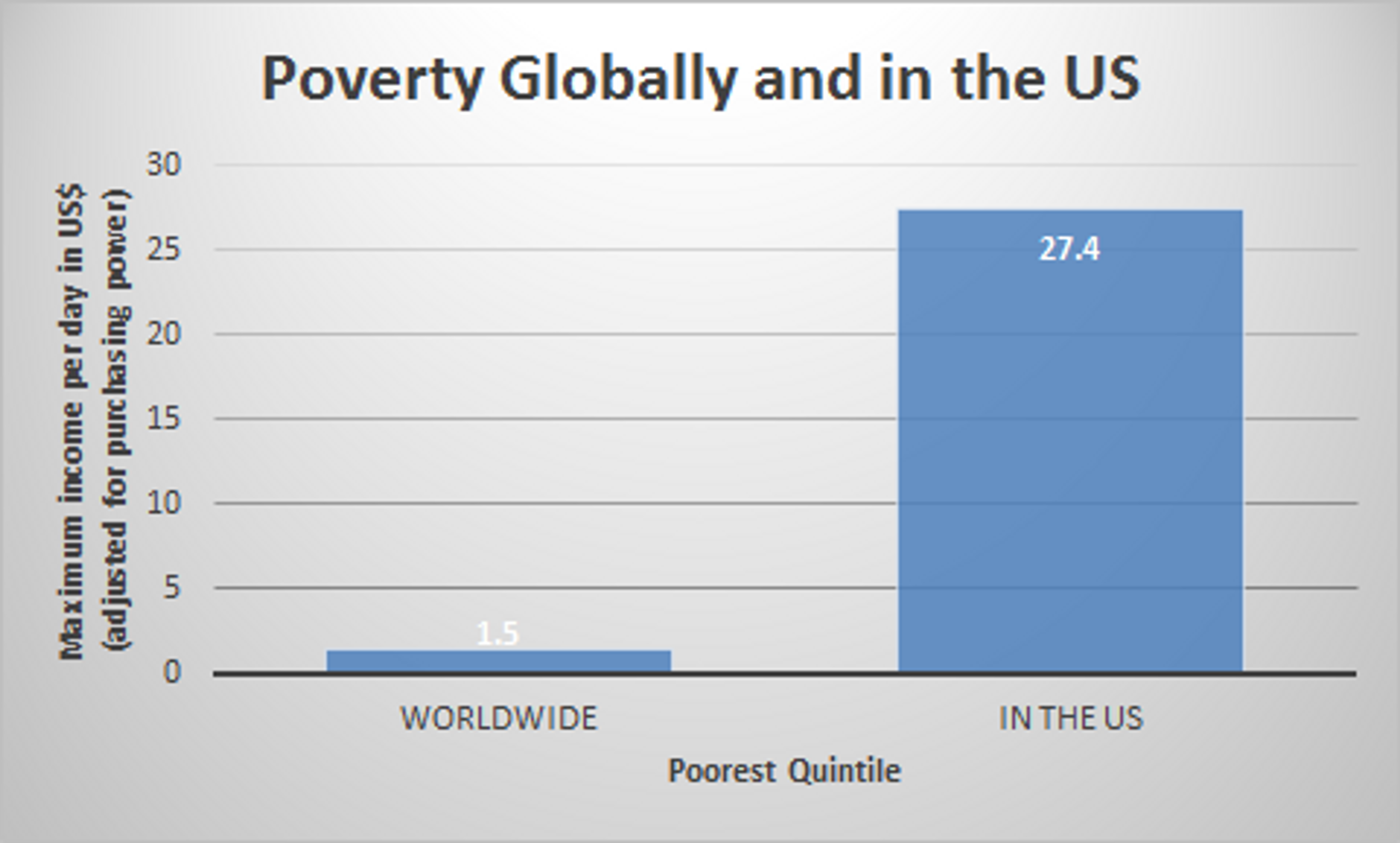

68% of the improvement in human health is down to technical improvements, such as vaccines, micronutrient fortification and deworming medicine, while higher income accounts for only 3%. For example, Sub-Saharan Africa’s real per capita income in 2008 was just over half that of England in 1870, and yet child mortality rates are two thirds lower in Africa in 2008 than in England around 1870.[2]

Under five Years of Life Lost (YLL) as a percentage of total YLL 1990 – 2050.[3]

Many critics of aid[4] underestimate the sheer scale of the progress that has been achieved as a result of public health interventions, which are often supported by foreign aid and international bodies such as the World Health Organization (WHO), UNICEF and the World Bank. In this blogpost, I will briefly describe and assess some of the most successful public health interventions of the 20th century.

This research relies to a large extent on the prior work done in this area by the Centre for Global Development, which has been published as Millions Saved. We have selected four of the twenty case studies from Millions Saved, examined the evidence given, and tried to provide reasonable estimates of cost-effectiveness. In addition, we look at an intervention not covered in Millions Saved – reducing tuberculosis in south east Africa.

We have strong reason to believe that that all of the interventions had high impact and very high cost-effectiveness.[5] All of them averted a Disability Adjusted Life Year (DALY)[6] for less than $50, some of them significantly less, with smallpox eradication, for example, saving a life (30-40 years) for $5. For context: the NHS will spend £30,000 to save a Quality-Adjusted Life Year (QALY);[7] and the world’s most effective charities avert a DALY for around $30.[8]

1. Smallpox Eradication

The smallpox eradication campaign (1967-1979) is by some distance the most effective program considered here and is one of the best public health interventions of all time. In 1967, smallpox affected 10-15m people and killed nearly a quarter of them.[9] The eradication campaign, with the help of the WHO, the US government and endemic countries cost only $300m.[10] It has saved at least 50m lives until today and provided enormous non-life-saving health benefits.[11]

Cost per life saved (1967-2014) = $5 per life.

This suggests that the intervention averted a DALY for significantly less than $1. Indeed, the benefits mentioned here do not include non-life-saving health benefits, such as blindness prevented. The eradication of smallpox was a truly extraordinary public health achievement.

2. Guinea worm reduction in Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa

Giving What We Can views interventions against Neglected Tropical Disease (NTDs) as having high cost-effectiveness.[12] One NTD, which until recently blighted much of Africa, is dracunculiasis AKA ‘guinea worm disease’. Guinea worm is contracted by drinking water bearing the guinea worm parasite. The disease is rarely fatal, but it does impose a significant disability and pain burden on those infected. On average, the disease incapacitates people for 8.5 weeks.[13]

In 1986, the WHO passed a resolution to eradicate guinea worm within 10 years.[14] In close collaboration with UNICEF, the US Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the WHO, the Carter Centre led the eradication effort.[15] To reduce the burden of the disease, the campaign encouraged the provision of safe water and water filtering through cloth, health education, surveillance of new cases and case containment.[16]

Global prevalence of guinea worm.[17]

In 1986, there were around 3.5m cases of guinea worm worldwide. Today, guinea worm is very nearly eliminated, with fewer than 200 reported cases in 2013.[18] We provide the following estimate of cost-effectiveness:

Cost per DALY averted (1986-2004) = $46.20.[19]

According to Givewell, the global program to eradicate guinea worm is ‘one of the success stories of global health’.[20]

3. Oral Rehydration Therapy in Egypt

In Egypt in 1978 all cause infant mortality was exceptionally high at 100 per 1000 live births, which meant that more than 100,000 infants died every year. At least half of these deaths were diarrhoea associated.[21] In the 1960s, it was discovered that diarrhoea could be treated effectively with a simple combination of salt, sugar and water, called Oral Rehydration Therapy (ORT).[22]

How to make ORT[23]

The Egyptian National Control of Diarrheal Disease Project (NCDDP), introduced in 1981, improved case management of diarrhoea through ORT and better feeding, especially breastfeeding.[24]

There is good evidence to show that ORT significantly reduced infant mortality in Egypt. From 1970-77, the reduction in infant mortality attributable to diarrhoea was 4.2%; from 1977-82 it was 7.8%; whereas from 1982-90 – the peak years of the NCDDP – it was 15.9%.[25] The rate of infant diarrhoeal deaths declined faster than the overall rate of infant mortality after the introduction of the NCDDP.

We conservatively estimate that the programme saved 100,000 lives in the 1980s.[26] According to the Centre for Global Development, the program cost $43m. It was funded by USAID and the Egyptian government and with assistance provided by UNICEF and the WHO.[27] So, we estimate that the program saved a life for $43m/100,000.

Cost per life saved = $430

This is exceptional. According to a paper in the British Medical Journal, ORT saved 50 million lives worldwide in the 20th century.[28]

4. Controlling tuberculosis in south east Africa

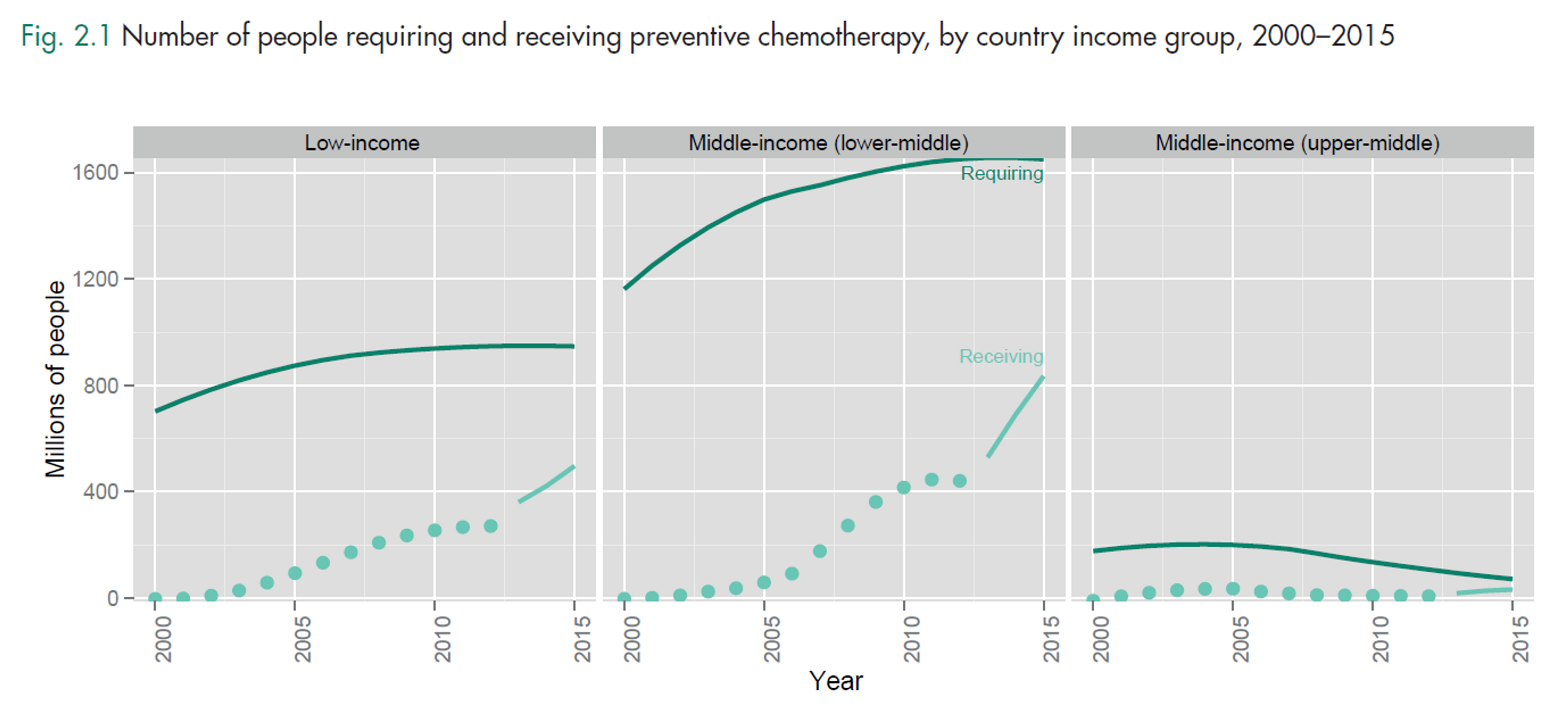

In 2012, 8.6m people fell ill with tuberculosis (TB) and 1.3m of them died (including 320,000 deaths from HIV positive people). In Malawi, Tanzania and Mozambique, national tuberculosis control programmes making use of short-course chemotherapy proved a highly cost-effective tool in the battle against TB.

TB is caused by bacteria (Mycobacterium tuberculosis) that most often affect the lungs. It is highly contagious.[29] Efforts to control TB have been significantly setback by the rise of HIV in the 1980s and 90s, as the two infections co-exist in large numbers of people. In the mid 1960s new drugs were discovered which allowed short-course chemotherapy treatment. This was testimony to the wisdom of the British Medical Research Council, which provided long-term support for tuberculosis research.[30]

In the 1980s, short-course chemotherapy was introduced and rapidly expanded in Malawi, Tanzania and Mozambique.[31] In all three countries, the cure rate for short-course chemotherapy ranged from 70% In Mozambique to 87% in Malawi, whereas the average cure rate for standard chemotherapy was 40-50%.[32] Despite the impact of the HIV outbreak on TB death rates, the chemotherapy cure rate remained largely unaffected by the HIV outbreak.[33] According to De Jonghe et al, the average cost-effectiveness of the intervention was:

Cost per year of life saved = <$6< big="">

According to the WHO, an estimated 37m lives were saved by tuberculosis treatment from 2000-2013.[34] As the tuberculosis situation improves in the developed world, it is nonetheless deteriorating in the developing world.[35] We hope that in the future, the poor will be able to afford the same healthcare resources as the rich today.

5. Preventing Iodine Deficiency Disease in China

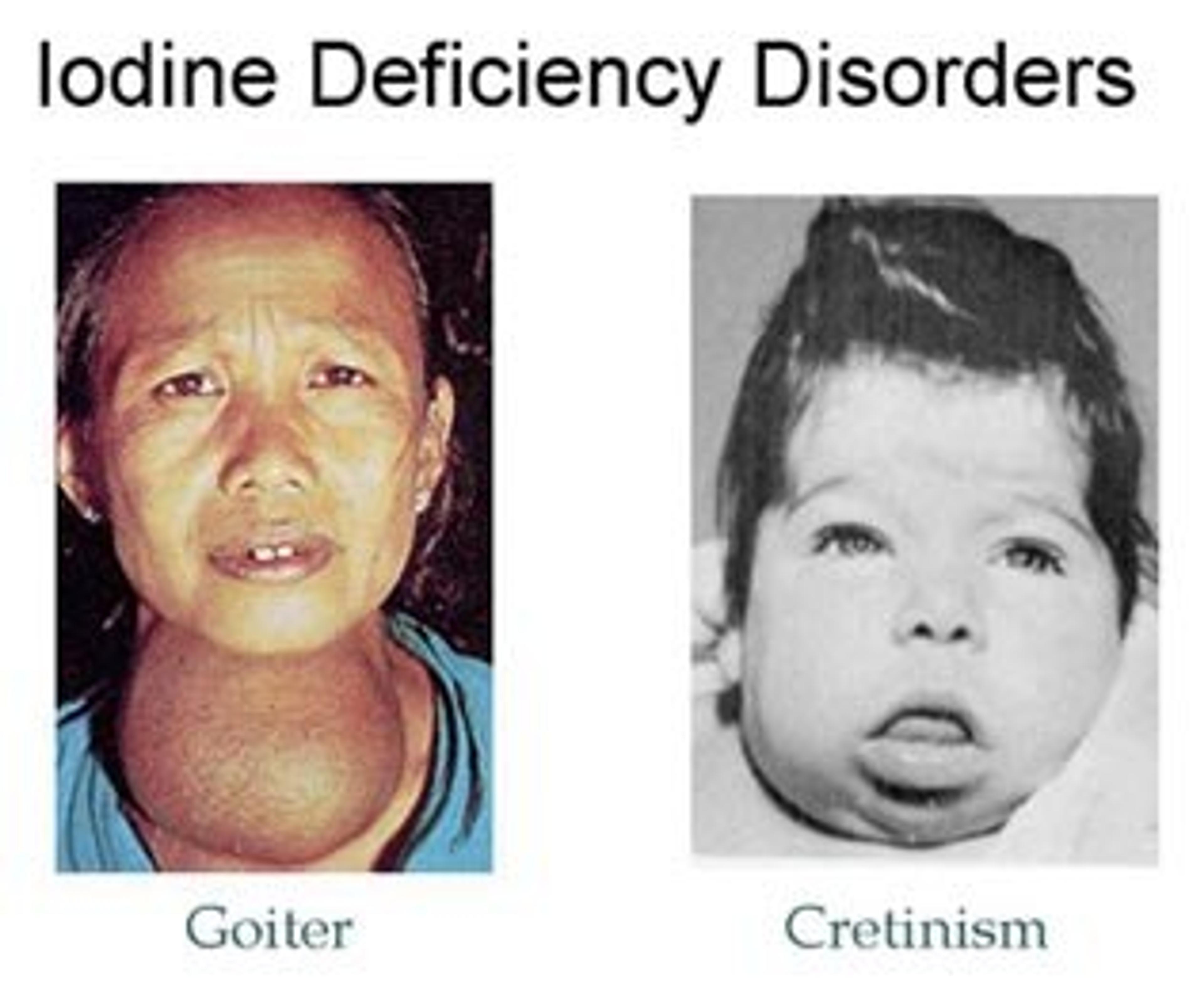

Iodine Deficiency Disorder (IDD) is the world’s leading, and most easily preventable, cause of mental illness, with around 50m sufferers today.[36] In severe cases, IDD can cause cretinism and in more mild ones causes goitre.

In 1993, 370 million Chinese people lived in IDD endemic areas, which was 40% of the global at-risk population.[37] The economic cost to China is estimated to be $50bn.[38] After becoming aware of the scale of the problem, China launched the National Iodine Deficiency Disorders Elimination Program in 1993. The program made regions aware of the problem of IDD; strengthened the capacity of the salt industry to iodise; improved monitoring of the quality of salt; and banned non-iodised salt.[39] According to Goh, as a result, the rate of goitre (an illness caused by IDD) among children aged 8-10 fell from 20.4% in 1995 to 8.8% in 1999.[40] We have deduced the following cost-effectiveness estimate:

Cost per DALY = $24

According to The Copenhagen Consensus salt iodisation was the most cost-effective and desirable intervention available to the world in 2012.[41]

Conclusion

The achievements of these public health interventions are enormous. They are all large-scale, national and international programs which have brought massive benefits at very low cost. The focus here has been chiefly historical, but the successes of the past may guide us towards success in the future. Humanity has done a great deal of good. The challenge we now face is to do the most good possible while we can.

References

- Copenhagen Consensus: How much have global problems cost the world?

- Pages 15, 16 of Assessment Paper: Human Health

- Page 57 ofAssessment Paper: Human Health

- See William Easterly, The White Man’s Burden : Why the West’s Efforts to Aid the Rest Have Done so Much Ill and so Little Good (New York: Penguin Press, 2006); Dambisa Moyo, Dead Aid : Why Aid Is Not Working and How There Is Another Way for Africa (London: Allen Lane, 2008).

- The full report provides a more thorough examination of the evidence.

- To determine the number of DALYs lost due to a disease, a weight factor that reflects the severity of the disease on a scale of zero (perfect health) to one (death) is assigned to the disease. See Measuring Benefits

- Nancy Devlin and David Parkin, “Does NICE Have a Cost-Effectiveness Threshold and What Other Factors Influence Its Decisions? A Binary Choice Analysis,” Health Economics 13, no. 5 (2004): 437–52.

- See for example Give Well: a model for cost-effectiveness of interventions

- Ruth Levine, Case Studies in Global Health : Millions Saved (Sudbury, Mass; London: Jones and Bartlett, 2007); Frank Fenner et al., “Smallpox and Its Eradication,” 1988, 1363, . The individual case study from Millions Saved is available here

- Fenner et al., “Smallpox and Its Eradication,” 1365–1366.

- [here]( Levine, Case Studies in Global Health; Fenner et al., “Smallpox and Its Eradication,” 1363. The individual case study from Millions Saved is available <a href=).

- Giving What We Can: Neglected Tropical Diseases

- Ernesto Ruiz-Tiben and Donald R. Hopkins, “Dracunculiasis (Guinea Worm Disease) Eradication,” Advances in Parasitology 61 (2006): 280–282.

- “WHO | Dracunculiasis (guinea-Worm Disease),” WHO, accessed September 12, 2014.

- Levine, Case Studies in Global Health.

- “WHO | Dracunculiasis (guinea-Worm Disease).”

- Ibid., 303.

- “WHO | Dracunculiasis (guinea-Worm Disease).”

- For an explanation of how I arrived at this figure, see the full report.

- Give Well: Cost-Effectiveness of Guinea-Worm Eradication. Givewell notes that the cost of completing eradication may be much greater.

- M. EI-Rafie et al., “Effect of Diarrhoeal Disease Control on Infant and Childhood Mortality in Egypt: Report from the National Control of Diarrheal Diseases Project,” The Lancet, Originally published as Volume 1, Issue 8685, 335, no. 8685 (February 10, 1990): 334–38, doi:10.1016/0140-6736(90)90616-D.

- Ibid., 52.

- Rehydrate.org

- Miller and Hirschhorn, “The Effect of a National Control of Diarrheal Diseases Program on Mortality.”

- EI-Rafie et al., “Effect of Diarrhoeal Disease Control on Infant and Childhood Mortality in Egypt,” 335.

- See Miller and Hirschhorn, “The Effect of a National Control of Diarrheal Diseases Program on Mortality”; EI-Rafie et al., “Effect of Diarrhoeal Disease Control on Infant and Childhood Mortality in Egypt.” The CDG case study somewhat misleadingly reports this figure at page 7 of this report

- Page 7 of this report . I have been unable to get my hands on the stated source for the $43m figure. Miller and Hirschhorn say that the grant assistance totalled $32m. See Miller and Hirschhorn, “The Effect of a National Control of Diarrheal Diseases Program on Mortality.”

- Ibid.

- “WHO | Tuberculosis (TB).”

- Ibid.

- Eric De Jonghe et al., “Cost-Effectiveness of Chemotherapy for Sputum Smear-Positive Pulmonary Tuberculosis in Malawi, Mozambique and Tanzania,” The International Journal of Health Planning and Management 9, no. 2 (April 1, 1994): 154–155, doi:10.1002/hpm.4740090204.

- Ibid., 172.

- Ibid., 173.

- “WHO | Tuberculosis (TB).”

- Murray, “A Century of Tuberculosis.”

- “WHO | Micronutrient Deficiencies - IDD,” WHO, accessed September 17, 2014, http://www.who.int/nutrition/topics/idd/en/; Levine, Case Studies in Global Health.

- T. Ma, J. Guo, and F. Wang, “The Epidemiology of Iodine-Deficiency Diseases in China,” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 57, no. 2 Suppl (February 1993): 264S.

- Levine, Case Studies in Global Health.

- Ibid.

- Chor-Ching Goh, “Combating Iodine Deficiency: Lessons from China, Indonesia, and Madagascar,” Food & Nutrition Bulletin 23, no. 3 (September 1, 2002): 280–91.

- “Copenhagen Consensus 2012 - Outcome” accessed September 17, 2014,. See the assessment paper here.