The most cost-effective health intervention? Killing parasitic worms, malaria mosquitos and HIV with one stone.

An interview with Dr. Martial Ndeffo Mbah and Laura Skrip from Yale University about how mass drug administration against Schistosomiasis might help reduce Malaria and HIV infections

This is part I of a series of updates on the effectiveness of our recommended charities. This week: the Schistosomiasis Control Initiative (SCI).

Today, we’ll be talking about some exciting new research that has the potential to change our charity recommendations.

You probably know that two of most effective charities are the Against Malaria Foundation (AMF), which distributes insecticide-treated bed nets to prevent malaria, and the Schistosomiasis Control Initiative (SCI), which delivers Mass Drug administration to deworm people. Not only are these organisations among our recommended charities, but they also consistently come out on top of the charity rankings by Givewell and The Life You Can Save.

One of the reasons why stopping malaria is so important and effective is that, every year, there are more than 200 million cases and roughly 660,000 associated deaths. According to the Global Burden of Disease study [1], this translates to more than 80 million years of otherwise healthy life being lost to malaria (see our post on Disability adjusted Life years or DALYs). In comparison, even though schistosomiasis can be treated at a very low cost by means of mass drug administration (MDA), its associated DALY burden is comparatively small (about 25 times less than the years of life lost to malaria), at an estimated 3 million years of lost healthy life [2] (though a recent commentary argues that, in fact, it may be twice as high [3]).

But now a series of recent papers by Dr. Ndeffo Mbah, Laura Skrip, and colleagues from the School of Public Health at Yale University and Baylor College of Medicine suggest that mass drug administration to reduce schistosomiasis has some impressive side effects. After executing a computational modeling tour de force, they found that treating schistosomiasis might reduce - with great effectiveness [4] - both malaria [5] and HIV [6] infections (due to reduced immunodeficiency and reduced female genital schistosomiasis).

Their analysis suggests that (depending on MDA efficacy) averting one HIV case through treating schistosomiasis costs as little as US$51.68–259.31. If we assume that 20 DALYs are lost per infected adult [7], this translates to US$2.58-12.97 per DALY averted (our calculation, uniformly weighted with a 3 percent discount rate as per DCP convention). The cost of treating schistosomiasis with a combination of albendazole and praziquantel is already among the most cost-effective interventions out there ($177 per DALY averted) [8]; adding the benefit of reduced HIV infections makes it even more impressive. Moreover, a recent Cochrane review [9] suggests that there is evidence of benefit in terms of slower disease progression for deworming HIV co-infected adults.

If you are looking for yet another reason to donate to SCI, it turns out that treating schistosomiasis also has the potential to fight malaria. In another paper, the same authors suggest that (depending on context) MDA reduces prevalence of Malaria by as much as an impressive 5%.

Since schistosomiasis, HIV/AIDS, and malaria are particularly prevalent in Sub-Saharan Africa and many people are co-infected, this has the potential to catapult mass schistosomiasis treatment to the top of all health interventions, especially when combined with water sanitation efforts.

We sat down with Martial and Laura to talk about their research, how you can infer causality without randomized controlled trials, the need for synergistic approaches to combat neglected tropical diseases and the importance of data sharing.

About:

Martial Ndeffo Mbah holds a PhD from the University of Cambridge and is currently an Associate Research Scientist in Epidemiology (Microbial Diseases) at the Center for Infectious Disease Modeling and Analysis, School of Public Health at Yale University. His primary research interest is computational modelling of neglected tropical diseases.

Laura Skrip is a PhD student at the Center for Infectious Disease Modeling and Analysis at the School of Public Health at Yale University. Her main research interest is dynamic transmission modelling of neglected tropical diseases.

Your lab has published a few papers on the positive side effects of mass drug administration against schistosomiasis. Your most recent paper in PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases suggests that if you give people drugs against schistosomiasis, this may actually reduce the prevalence of malaria. Can you tell us a bit more?

Martial: The idea for the paper came from a number of conversations that we've had with Peter Hotez at Baylor College of Medicine in Texas, one of the coauthors on that paper, along with with some other collaborators at Yale. We were talking about the co-infections that you have with a lot of Helminth diseases [infections by parasitic worms], and malaria especially. Looking at this, and also taking into account the fact that these co-infections, and comorbidity are highly prevalent in many African settings, one of the things that really drove us to do this research was the fact that so little work has been done on that very interesting problem either from the fieldwork perspective or especially from a modelling perspective.

When we started looking into the literature, the only field study that we were able to find that was addressing the interaction that you have, especially causal interaction between schistosomiasis, schistosoma mansoni and malaria, in particular falciparum, was a study that was done in Senegal some years ago. Looking at that study and our previous experience modelling interactions between schistosomiasis, female genital schistosomiasis and HIV, we decided that it was really appropriate to do a study on this to raise the profile and to raise awareness about the fact that schistosomiasis (especially schistosoma mansoni, which is widely spread in Africa), has been observed to have a strong correlation with an increased risk of malaria, especially among children.

Regarding the causal relationship: there's a very strong overlap in Sub-Saharan Africa between locations with lots of schistosomiasis and lots of malaria and so one might think this is just a correlation. But you write about how, if you are infected with schistosomiasis, then certain parts of your immune system might be very prone to malaria and also you're the first to create a mathematical model that suggests that it's indeed causal, that schistosomiasis exacerbates malaria infection. Is that correct?

Martial: Yes. First of all, I'd like to say that there are quite a number of biologically plausible reasons why we believe that it's really a causal relationship, especially among children who have a very high burden of infections. Other researchers have studied some of the biological reasons for coinfection as well as statistical measures of causality.

For example, the study that was conducted in Senegal was done over a period of time in order to compute the relative risk of malaria infection in the presence of schistosomiasis infection. If you have some quite robust statistical results and some plausible biological mechanisms that are in line with that, you have a good story. The mathematical model brought about a new argument for a causal link. We do not see this as an end to the debate. We hope that this will encourage researchers to continue to do field studies along this line, because this is a very important problem that needs to be addressed as soon as possible.

What's the effect size that your model suggests? If you were to do mass drug administration against schistosomiasis, how much would you reduce new malaria infections? Can your model make predictions on that?

Martial: I think that will definitely depend on the setting. It will depend on how prevalent malaria and schistosomiasis are in the location. But according to some calculations we've done, there is a potential reduction of 5%, which is definitely a lot. And that is just prevalence, which doesn't take into account the fact that a lot of these children will have multiple episodes of malaria during a year. Because we don’t look at severe malaria, our study is conservative in the sense that it does not account for potential avoidance of malaria induced deaths.

Laura: Another thing to note is that the reduction in malaria associated with praziquantel administration for schistosomiasis can be even greater if done in combination with artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACT). Some of our findings suggest that the effectiveness of ACT for reducing malaria prevalence and symptomatic malaria episodes is less in areas of co-endemicity with schistosomiasis. So by mass treating against schistosomiasis, you’re also potentially improving the impact of malaria interventions.

You also have another paper from 2013 published in Proceedings of The National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) about reduction of HIV when you do mass drug administration against schistosomiasis. Can you talk a bit about that too?

Martial: It's a study that we started a few years ago in collaboration with Doctor Kjetland, who initially conducted a cross-sectional study among women in rural areas in Zimbabwe. Doctor Kjetland and collaborators observed that there was a very strong correlation between female genital schistosomiasis and HIV infection. As with malaria, there was a very strong biological reason why we would believe that there is a causal link, that is, that female genital schistosomiasis increases the risk of HIV transmission. This is not just because the two diseases overlap in the same regions, but also because women usually get female genital schistosomiasis long before they become sexually active. We know that sexual transmission is the main route for HIV transmission in Africa, so in general women get female genital schistosomiasis before getting HIV. And female genital schistosomiasis is a long lasting disease. Meaning that when they get it, they can have it even for the next 30 or 40 years. Sometimes, they have it for the rest of their lives.

So even if they are treated, the symptoms of female genital schistosomiasis remain even after deworming. Is that true?

Martial: Yes. That is really the big problem with that. To really turn around this trend you have to treat them before they start developing the symptoms, at a very young age. Using the data collected from Zimbabwe, we developed a mathematical model without making any assumptions about the direction of the causal relationship. We analyzed the data with the new model, to see if we got a result that agreed with what biology seems to say: that female genital schistosomiasis is an increased risk factor for HIV.

The model showed that. In doing that we brought new information, a new argument from a modelling perspective, to the table, that supports the hypothesis that the presence of schistosomiasis increases the risk of HIV infection among women in Africa.

You have another paper in PLoS neglected tropical diseases that talks about the cost effectiveness of this intervention. Your analysis suggests that in terms of HIV reduction, that it's immensely effective to reduce schistosomiasis as compared to traditional HIV interventions. Can you say what is the order of magnitude there? How big is the reduction of new HIV infections?

Martial: First I want to say we look at two things in the PLoS NTD paper, we only look at mass treatment and what effect it has on reducing schistosomiasis and HIV. This intervention is cost-saving, which is very, very rare for a lot of public health interventions. Basically, by doing these interventions in rural areas in Sub-Saharan Africa, you'll be able to reduce the cost of healthcare in a country, simply because of the large burden of HIV and schistosomiasis that you are going to avert. But in the PNAS paper, we look at a much broader community-based intervention approach where we meet mass drug administration with provision of water, sanitation, and also hygiene education.

Can you say a bit more about the water sanitation aspect? Because some people who read this might think, "We give the deworming pill - and then the schistosomiasis vanishes completely." But because of rapid reinfection, we have a baseline burden of schistosomiasis that remains, even after the population is treated, if we don’t work on water sanitation. Is that true? That's what I hear from some schistosomiasis researchers. And is that why it's particularly cost effective to also do water sanitation projects at the same time?

Laura: I think just focusing on sustainable development projects to promote hygienic and sanitary behavior would reduce exposure to worms. That could include not using local streams or rivers for bathing, and just decreasing exposure to contaminated water.

Are you planning to do a cost-effectiveness analysis on the malaria data too? Is that in the works and going to be the next paper?

Martial: We are considering other projects and exploring some other interaction as well. We are always open to getting new data, getting a better sense of what's happening in local community, and developing more realistic models.

Cost effectiveness analysis on malaria data is one of them?

Martial: Definitely.

That's interesting. Here at Giving What we can, two of our top recommended charities try to target NTDs. One being the Against Malaria Foundation, and they distribute insecticide-treated bed nets. Then we also recommend the Schistosomiasis Control Initiative. Do you think the Schistosomiasis Control Initiative would be - in the light of this new data - in a particularly good place to claim they are actually in fact treating malaria in quite a cost-effective way?

Martial: I think that there is a need of becoming more synergistic in the way we're tackling tropical diseases in Africa. It's one of the things that has been highly advocated by Peter Hotez and many other people in the field. We realized, for example, that when we were doing the research for the PNAS paper, one of the things that motivated us was the fact that even for schistosomiasis control you have two different efforts through which this disease can be controlled, but the people involved don't necessarily talk to each other.

On the one hand you have an engineering approach by providing clean water, providing sanitation in different communities, where the main goal is not necessarily the fight against schistosomiasis. But by doing that, they're actually fighting against schistosomiasis, and they're fighting against many of the water-borne diseases - cholera and many others.

On the other hand, you have Mass Drug Administration, which also does a very good job in fighting against the disease. But most of the time these two groups don’t talk to each other. An important question is: how can they harmonize their approaches, be more synergistic and get higher benefits for the local population, and better reach their goals?

I think that the same thing should be done with malaria. That is one of the reasons why we wrote these papers - to try to get these different agencies to start talking to each other, to start harmonizing their approach, and to really see the mutual benefit in a more holistic approach in fighting these diseases which are really intertwined one with another.

Lastly, is there anything that people can do to assist with research on NTDs?

Martial: Sometimes it is difficult to get the data that we need. It would be great if agencies and researchers could embrace open science and open sharing of data. That would help us a lot with our research.

Laura: Co-infection involving at least one NTD is prevalent throughout many regions of Africa, Southeast Asia, and Latin America. As Martial mentioned earlier, there could be great impact in synergistic interventions strategies. Similarly, it will be increasingly important to not always research the diseases in isolation but to study longitudinal changes in prevalence and incidence both before and during intervention implementation.

Thank you both very much for the interview!

Figures

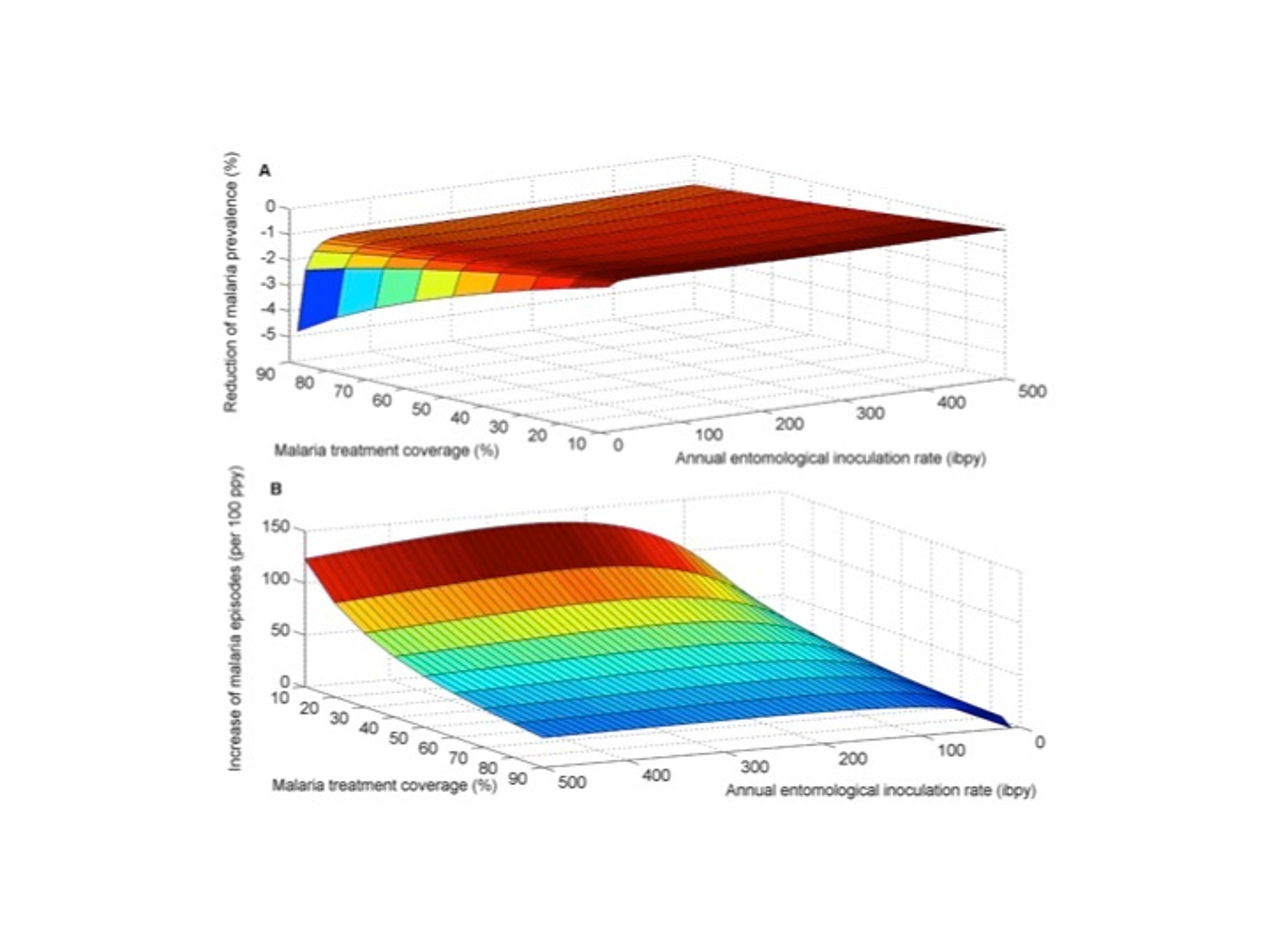

The impact of the interaction between S. mansoni and malaria on the effectiveness of ACT for reducing malaria prevalence and symptomatic malaria episodes.

We compared (A) the proportional reduction of malaria prevalence with and without interaction and (B) the increase in symptomatic episodes of malaria due to elevated susceptibility to malaria mediated by S. mansoni infection. S. mansoni high worm burden was assumed to increase the risk of malaria infection by 85% , consistent with epidemiological studies [6].doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0003234.g002

The impact of mass praziquantel administration on malaria prevalence over a six-year intervention period.

The proportion of symptomatic malaria cases that received treatment was 70%. Interaction between S. mansoni and malaria and the effect on malaria prevalence for annual entomological inoculation rate (AEIR) equals (A) 10 infective bites per person annually and (B) 100 infective bites per person annually. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0003234.g003

References

- Murray, Christopher JL et al. "Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010." The Lancet 380.9859 (2013): 2197-2223.

- Murray, Christopher JL et al. "Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010." The Lancet 380.9859 (2013): 2197-2223.

- It's Time to Dispel the Myth of “Asymptomatic” Schistosomiasis. 2015. 4 Mar. 2015

- Mbah, Martial L Ndeffo et al. "Potential cost-effectiveness of schistosomiasis treatment for reducing HIV transmission in Africa–the case of Zimbabwean women." PLoS neglected tropical diseases 7.8 (2013): e2346.

- Mbah, Martial L Ndeffo et al. "Impact of Schistosoma mansoni on Malaria Transmission in Sub-Saharan Africa." PLoS neglected tropical diseases 8.10 (2014): e3234.

- Mbah, Martial L Ndeffo et al. "Cost-effectiveness of a community-based intervention for reducing the transmission of Schistosoma haematobium and HIV in Africa." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 110.19 (2013): 7952-7957.

- Murray, Christopher JL, and Alan D Lopez. "Alternative projections of mortality and disability by cause 1990–2020: Global Burden of Disease Study." The Lancet 349.9064 (1997): 1498-1504.

- "Errors in DCP2 cost-effectiveness estimate for deworming ..." 2011. 25 Mar. 2015 http://blog.givewell.org/2011/09/29/errors-in-dcp2-cost-effectiveness-estimate-for-deworming/

- Walson, Judd L, Bradley R Herrin, and Grace John‐Stewart. "Deworming helminth co‐infected individuals for delaying HIV disease progression." The Cochrane Library (2009).