How Do Poor People Get Money?

About 50% of the poor living in Indonesia, 72% in Cote d’Ivoire, 84% in Guatemala, and 94% in Udaipur report working multiple jobs in order to get their income -- typically one agricultural and one non-agricultural, though not always.

Most non-agricultural jobs involve self-employment as a business owner. Typically, a member of the poor household will migrate (about 60% of families), leaving for a median of one month to find employment in a nearby city. Others will perform a job earlier in the day, like selling food, and then go out and perform another job, like selling textiles, collect trash, or general labor.

Generally these entrepreneurial jobs done by the poor do not require skills. In Hyderabad, jobs of the poor breakdown to 17% general stores, 11% tailors, 8% fruit and vegetable sellers, 6.6% telephone booth operators, 6.3% milk sellers, and 4.3% auto owners. Of these, only tailoring requires a specialized skill that takes awhile to acquire.

Additionally, about 76% of the poor report at least one member of their household working for a public employment program. Many governments provide safety-net “food for work” programs, which entitle some days of physical labor under government employment at a pre-announced, low wage. Unfortunately, this kind of work is rare and is often given out in a way that discriminates against the poor.

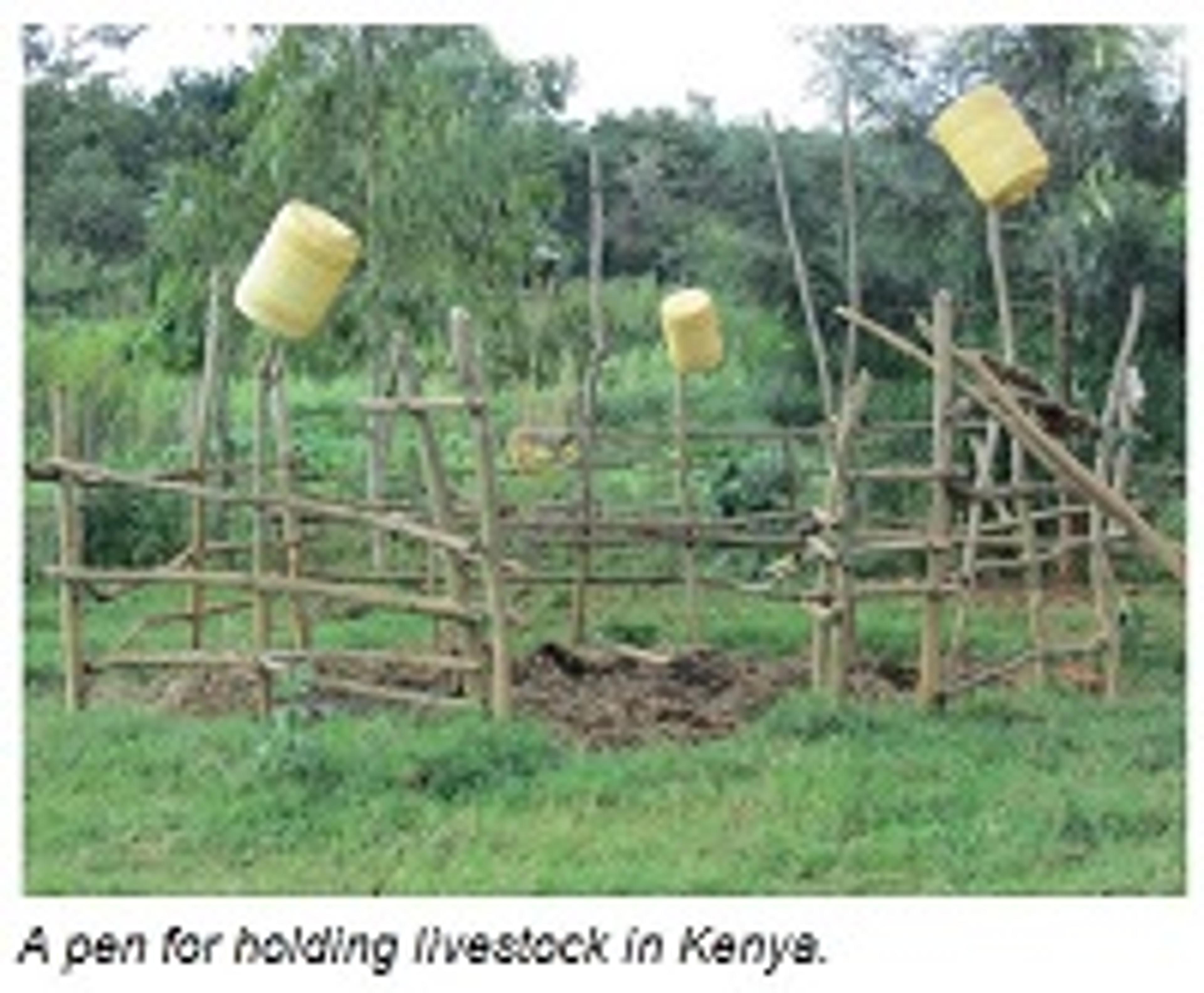

Another interesting question is how the poor would spend additional money, if they got it. GiveDirectly, by giving cash transfers in $1000 chunks, has been able to find out. An informal survey conducted by them and shared with GiveWell found that 67% of the money spent went into home improvement (replacing a thatched roof with an iron-sheet roof), 9% went to other (like school uniforms or a motorcycle), 9% went to livestock, and 4% went to food. However, this survey was only in Kenya, and other areas might spend differently.

How Do the Poor Save and Get Credit?

Typically, the poor don’t actually have access to a safe place to save money at a reasonable rate of return. Only 14% of poor households have a savings account (with the exception of Cote d’Ivoire, where the number is 79%). Even stashing cash in a pillow or a home doesn’t work well because of high inflation and rates of theft. Additionally, the poor, like everyone else, have problems resisting the temptation to spend money they have at hand, both when family members demand access to it, or when given the option to buy the same indulgences people in developed countries struggle to resist.

There also is little access to insurance. Less than 6% of the poor have access to any kind of health insurance. Generally, insurance is instead provided through friends and relatives as a type of loan exchange -- 75% of poor households report making loans, 65% report borrowing money, and 50% report both. The most common form of “insurance” to handle economic stress is eating less, taking children out of school, and foregoing medical treatment.

This lack of insurance or saving leads the poor to under-invest because they cannot accumulate financial assets, or afford to take risks. Poor families do not specialize in skills and they operate their businesses at a remarkably small scale. Poor families have access to very limited markets and infrastructure and suffer from a lack of access to credit.