Executive Summary

This article is about using psychology to make it easier to do good through effective giving. An overview is provided below.

1. Introduction to effective giving

- Introducing effective altruism, effective giving, intended audience, scope and background

2. Convince yourself giving effectively is a good idea

- By appealing to the opportunity of doing good, considering the 100x multiplier

- By appealing to your sense of morality, using rationality and intellectual honesty

- By appealing to the notion that it’s in your self-interest to give, leading to a more meaningful life

3. Use psychological mechanisms to give and to continue giving

- By identifying and questioning your conditional assumptions about giving

- By framing giving as exposure therapy to make it less scary

- By mitigating endowment effects, reducing attachment to “your” money

- By using stories and rituals to increase motivation to save “statistical” lives

4. Use other mechanisms to balance your focus on doing good

- By detaching from the identity of an effective altruist using humility, self-irony and meditation

If you are already familiar with effective giving, you might skip part 1 and go directly to part 2.

1. Introduction to effective giving

This article draws on the Effective Altruism (EA) movement, in which people try to use careful reasoning and science to do as much good as possible in the world. For an introduction to EA, see this video. There are many tracks within this movement, like doing research on existential risks, impacting policy, etc. This article assumes the reader wants to use giving at least as one of his/her strategies for doing good, donating to effective causes to for example increase wellbeing and reduce suffering in the world. The article is mainly aimed toward people who have a significantly higher income than the global average (e.g., over USD $30,000 in yearly income).

In the reasoning below, it is also assumed that we should value lives in other countries just as much or close to as much as we value people close to ourselves, reducing our proximity bias (Singer, 2016).

Some psychological mechanisms for supporting your giving are out of the scope of this article, including the following:

- Being part of a community where giving is common and normalized (e.g., EA)

- Taking short-term or long-term pledges like the Giving What We Can Pledge

- Traveling to less rich countries for a more direct experience of inequality

- Having religious beliefs that support giving

In the beginning, I was scared to give even small amounts (which seems ridiculous in retrospect given that I had a decent job in a high-income country). Assuming that other people might experience this fear of giving as well, I wrote this article to summarize some useful psychological tools to support others in their aspirations toward effective giving.

2. Convince yourself giving effectively is a good idea

Do you feel like you could perhaps give more to charity, but you’re hesitant to take the first steps? This section is mainly for people who are in this situation, for example people who just recently discovered the EA movement. It provides arguments to help you convince yourself that effective giving is a good idea in the first place. If you are already well read on EA and you’re already giving, consider skipping directly to section 3: Use psychological mechanisms to give and to continue giving.

Appeal to the opportunity

If you live in a first-world country and haven’t already studied global income levels, you may not know that you likely belong to a much higher income percentile than you would guess. For example, earning USD $45,000 per year would put you in the top 2% globally (find out where your income level positions you globally using this calculator). Added life satisfaction (or happiness) from income diminishes more quickly as income increases (see this 80000 Hours article).

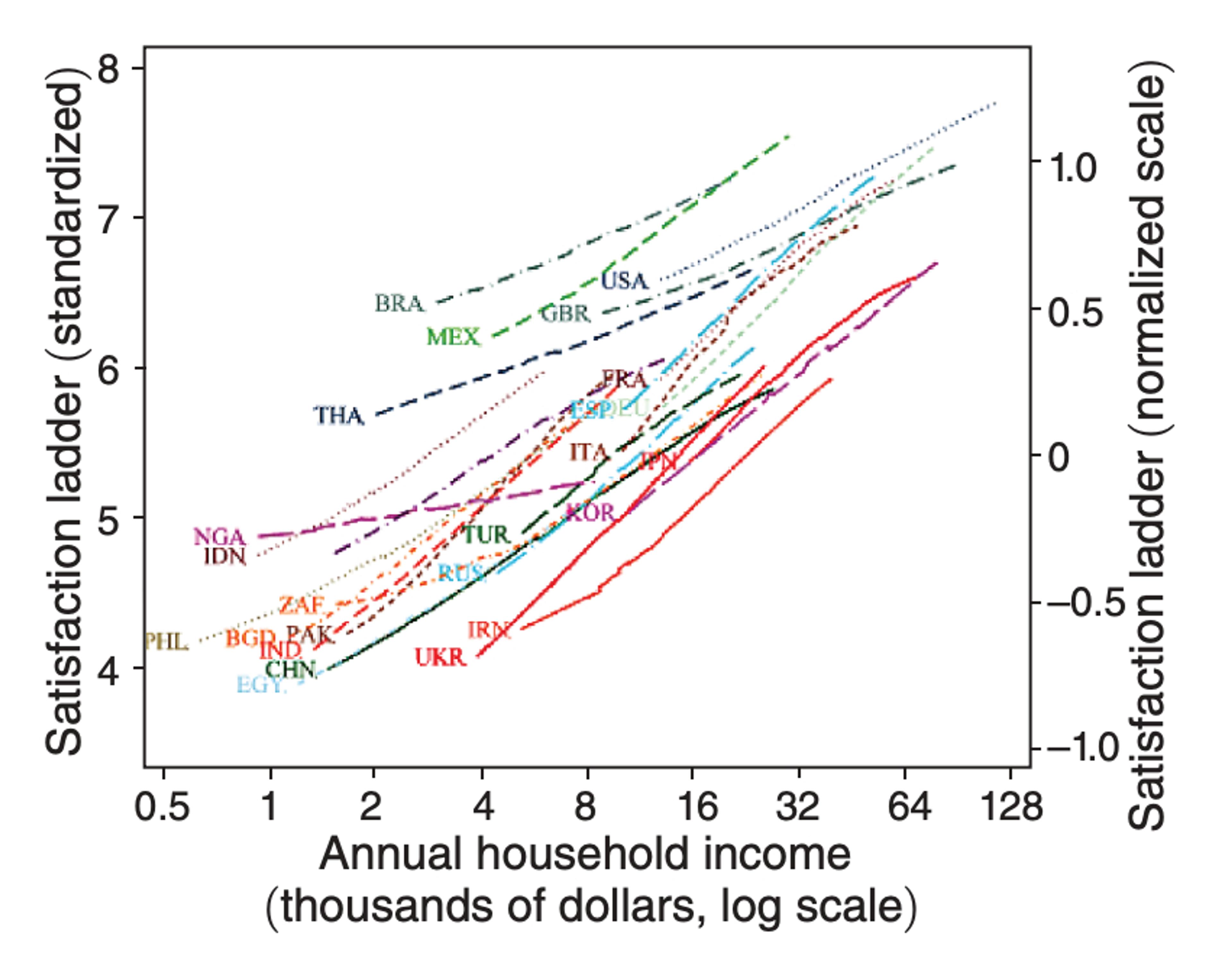

This income–satisfaction relationship is also often visualized as a linear increase on a logarithmic (log) scale, with the income being doubled for each step on the x-axis:

(Stevenson & Wolfer, 2013)

This implies that money, insofar as satisfaction is concerned, is more valuable to those with less money. Along these lines, studies have shown that when the richest people give to the poorest people, it gives the poorest people roughly 100 times more added life satisfaction than is sacrificed by the richest. In Doing Good Better, William MacAskill refers to this phenomenon as the “100x multiplier” on giving. He suggests a thought experiment: You are at a bar where you can buy beer for others for $0.05 per beer, or buy beer for yourself for $5 per beer — at such a bar, MacAskill says, you would likely be generous! Assuming that saving a life costs USD $3,600 (the amount suggested in Givewell’s list of top charities, in the cost-effectiveness estimates of the very best charities in the list), if you donate USD $300 per month, you would save one life per year. Assuming you continue giving at this rate for 40 years (and that the value of your donations hold), it would mean saving 40 lives — an immense opportunity to do good! Recognizing the opportunity itself can be motivating in a way that lifts us up rather than weighs us down, and some people in the EA movement suggest it might be the most sustainable motivating factor.

Appeal to morality, rationality and intellectual honesty

Most of us aspire to “do the right thing” and to behave morally, at least to some degree. The problem seems to be that by default, we tend to have very rough heuristics for doing this that are skewed by misconceptions, biases and lack of analysis, and these also apply to how we donate.

Starting with the foundation of aspiring toward morality and doing good, a natural next step is to also aspire toward careful analysis and intellectual honesty so that our efforts are not misguided; this is a cornerstone of the EA movement. Regarding donating to charity, research suggests one can increase impact by 10-100 times by giving to the most effective charities rather than to a typical charity (examples can be found here). Therefore, an important aspect of giving is to convince yourself that real impact is more important than self-gratification and “warm glow giving” (giving to the cause that you “feel” for). The latter is not rational if the goal is to reduce suffering; you’d be better off zooming out and looking at the full range of options and evaluating them systematically.

If you have grown up under favorable circumstances, then in the spirit of intellectual honesty, you might also see your donations as an acknowledgment that much of your success is due to these favorable circumstances. For example, you might have been born in a first-world country and given a good education, maybe along with favorable heredity and parenting. Taking this attitude can also be seen as not falling for the fundamental attribution error, by which people tend to overly attribute outcomes to personality and de-emphasize the effects of external circumstances. Under this illusion, we might tell ourselves that we have “earned” our income and position in the world through hard work and discipline when random circumstances explain more than we’d like to admit.

So if you can convince yourself to be rational in your choice of where to give, it can make a big difference, and you can then figure out ways to at the same time stay emotionally engaged and make your giving sustainable. If necessary, you can also try allocating a small share of your giving to the cause(s) that you feel for. Because “feeling” for a cause has been shown to be an important psychological mechanism, the following website was created to support people in giving more to effective charities by enabling them to create donation combinations that include both charities they feel for and really effective charities: https://givingmultiplier.org/.

MacAskill also outlines how people who don’t work in a neglected problem space tend to overestimate the impact of their careers, even when those careers seem well suited to make an impact, like working in healthcare. In one of the book’s examples, a medical student does an analysis of how many lives (in terms of quality-adjusted life years) he can save over a 40-year career in the US. The aggregate numbers for the value of healthcare in the US at first seem to indicate that a doctor saves 70 lives in a full career. But with a more careful analysis, accounting for the diminishing returns of adding one doctor to an already reasonably well-supplied workforce (and for contributions from nurses and other healthcare workers), the real number would be closer to 4 lives over a career. The analysis went on to suggest that if this doctor worked in Ethiopia instead of the US, he would save 300 lives in his career, since the impact on the margin would be magnitudes higher there.

If we donate from our income, it has a counterfactual impact on the margin — if you didn’t give, it’s generally not the case that someone else would step in and give that amount instead. So if you don’t work in a neglected and high-impact space, donating can also be seen as being intellectually honest about what has real impact. (For analyzing impact, this framework using “scale,” “solvability” and “neglectedness” is often used within the EA community.)

Appeal to self-interest

Another approach to convincing yourself to start giving, or to give more, is to consider that it might be the most logical thing to do out of self-interest, in that it may optimize for your own well-being. Studies have shown that the impact of increased income on happiness greatly diminishes at higher income levels. While there is still some remaining correlation after the plateau, it is less clear how much of it is causal, and other factors like relationships and a sense of purpose are far more important (see this article on money’s effect on happiness).

On the other hand, starting to give to charity can have a significant impact on happiness (Dunn et al., 2008; Dunn et al., 2014). For example, in one study, a group of people who were given money and told to spend it on other people reported being more happy after the spending than the control group that spent the money on themselves (see this article that has more examples and references).

Hence, if your happiness (maybe even sense of purpose) is more important than having more disposable income at higher income levels, giving to charity is the logical thing to do out of self-interest. For example, if you wake up one day and don’t feel great about going to work that day, you can tell yourself that the proceeds from your work that day will contribute to effectively helping someone, thereby giving your work more meaning. And later in life, when you consider whether you are happy with your life in retrospect, the answer might be a lot more positive if you know that you’ve truly helped a lot of people.

It is up to each reader to decide what combination of the above mechanisms will be effective and sustainable to motivate their giving.

3. Use psychological mechanisms to give and to continue giving

For those who are already convinced that giving effectively is a good idea, this section provides more psychological mechanisms to make it easier to begin, and to make giving more sustainable and increase total impact.

Identify and question your conditional assumptions

In cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), it is posited that people develop various “conditional assumptions” in the form “if X, then Y,” and that these assumptions often lead to rigid rules we follow, even if we are not aware of them and how they impact us. But we can often change these assumptions by questioning them, and by making different “behavioral experiments” in which we break one of these “rules” and see if its underlying assumptions are really true. In the case of giving, you might have assumptions that prevent you from starting to give, or from giving the amount that seems in line with your values. Examples include the following:

- “If I give and don’t see the direct effect, I will just feel impoverished.”

- “If I give, it will only have a very minor impact.”

- “If I give away more money, my friends will not respect me as much because I have less money.”

- “If I start giving, I will always feel as though I never give enough compared to what is morally justified.”

Once you have brainstormed what assumptions like these you might have, you can start questioning them. Here are some examples of questions you can use:

- Are there counterexamples in which this assumption is not true?

- Are there other people with different behaviors or attitudes, for which this rule doesn't seem to hold? If so, what does that suggest?

- What purpose does this assumption hold for me? Is that purpose still something I want to prioritize?

- Are there other weaknesses in the argument of the assumption (like heuristics or biases)?

- How could I seek other counterfactual evidence to this assumption that is not available to me now?

- What would it be like to live without this assumption?

- Are there behavioral experiments I could do to try out an alternative behavior and assumption that are more in line with my values? Can I imagine a way of making it fun and sustainable?

Frame giving as exposure therapy

If you are uncomfortable with the idea of giving away some of your income, you can think of your giving as exposure therapy. When people have debilitating fears, a psychologist might help them through gradual exposure to the thing they are afraid of; for someone with a phobia of spiders, the psychologist might first show them pictures of spiders, then videos, then a real spider in a glass container, and so on. The incremental exposure teaches the person that spiders might not be so dangerous after all. In the same way, if you earn a good salary and you are reluctant to start giving due to various fears, you can start with small amounts, and then after realizing nothing catastrophic has happened, you can increase the amounts over time. This “exposure therapy” framing of donating could also be applied to other types of giving, like giving from your time or refocusing your career to have more impact.

Mitigate the endowment effect

The endowment effect suggests that once we feel something is ours, we are reluctant to let it go. For example, if you buy a product in a store, you develop an emotional attachment to it as soon as you’ve paid for it, and immediately after leaving the store you might not want to sell it to someone even if that person offers slightly more than what you paid for it.

In the same way, once you earn money, you start to feel attached to it and it becomes harder to let go of it. Due to this effect, donating is often easier when you automatically transfer your donations as early as possible in the process. If you live in a country where it is easy for your employer to pay out the chosen amount of donations from your pre-tax salary, this might be a good solution; since the money in this case never even makes it to your bank account, you have less opportunity to feel possessive over it. Otherwise, automatically transferring your donation amount soon after it lands in your bank account might be the best option. In either case, you don’t need to “rediscover” your commitment and use mental discipline every time you feel you ought to donate.

On a different note, you might also think about how the endowment effect interacts with old age, passing away and inheritance. You might want to have a share of your intentional giving increase in value over many years on the stock market and in housing and other assets, and then give from these investments late in life or when you pass away. As you age, your body and energy level will likely create constraints on what you can do, and you might find that you have fewer cravings for things to spend your money on. At that point, it might be easier to let go of larger amounts. On the other hand, if your money will be an inheritance for someone, you might see a new endowment effect emerge — the relatives set to inherit the money may start to feel as though they own it, and it may be harder for them to let go of the money after it comes into their possession and donate it to effective causes.

You could also consider writing a testament that sets out what share of your money you intend to give upon passing away, even if you're now at a young age. This might increase the chance that it will actually happen, since you’ll have many years to get used to the thought of donating larger amounts. Of course, you can still decide to act on making the donations at an old age yourself — just have the testament state that any obvious big donations late in life can be considered donations from the intended final share given. Additionally, a testament might have positive side effects, making various things in life feel more meaningful; for example, buying a house may seem less self-centered and more like a long-term investment that will also help a lot of people after you’re gone.

Use stories and rituals

Our brains seem to like stories — we generally become more engaged by a compelling story than a set of facts, and, as noted by many serious meditators, we often become very attached to the stories we tell ourselves about who we are, what we do and why.

Given that the brain likes stories, we can try to use stories to motivate our own giving, making it more fun and sustainable. Stories are used to motivate giving all the time, but not always the most effective giving. For example, you might give to a person in your neighborhood because you can see them and imagine their story. Moreover, empathy (or pity) can be stirred by visual confrontation with a person suffering. But rational giving often does not involve seeing the individual who is suffering, and who in turn benefits from your giving; rational giving is about saving statistical lives — how can stories help us then?

When thinking in terms of statistical lives, you can create stories about the individuals who compose those statistical lives. Once you have saved your first statistical life (by donating USD $3,000-4,500 to effective causes), you can name this statistical person something like “Aaron” (starting alphabetically). Then you can celebrate with some like-minded people that you saved Aaron, and maybe keep an empty chair for Aaron or a mascot that represents him at the event. You can even imagine a story about Aaron and what he is doing now. All of these tactics build a story and help the brain understand that morally speaking, an unseen statistical life is worth just as much as a person we can see for ourselves.

Some people might think this is some kind of self-deception, but you can always remain aware that such stories are fictional, and regardless, story creation can be helpful in hacking the brain to better align your emotions with your values. Some meditators might also note that this is similar to what our brains are already doing anyway — creating fictional stories about ourselves. (See this video with Joscha Bach for inspiration on the topic: “You are a story that the brain tells itself about a fictional person.”)

Moving toward a morality where we think in terms of statistical lives can help us do a lot more good in the world, since it frees us from the constraint to donate only to causes where we see the direct effect.

4. Use other mechanisms to balance your focus on doing good

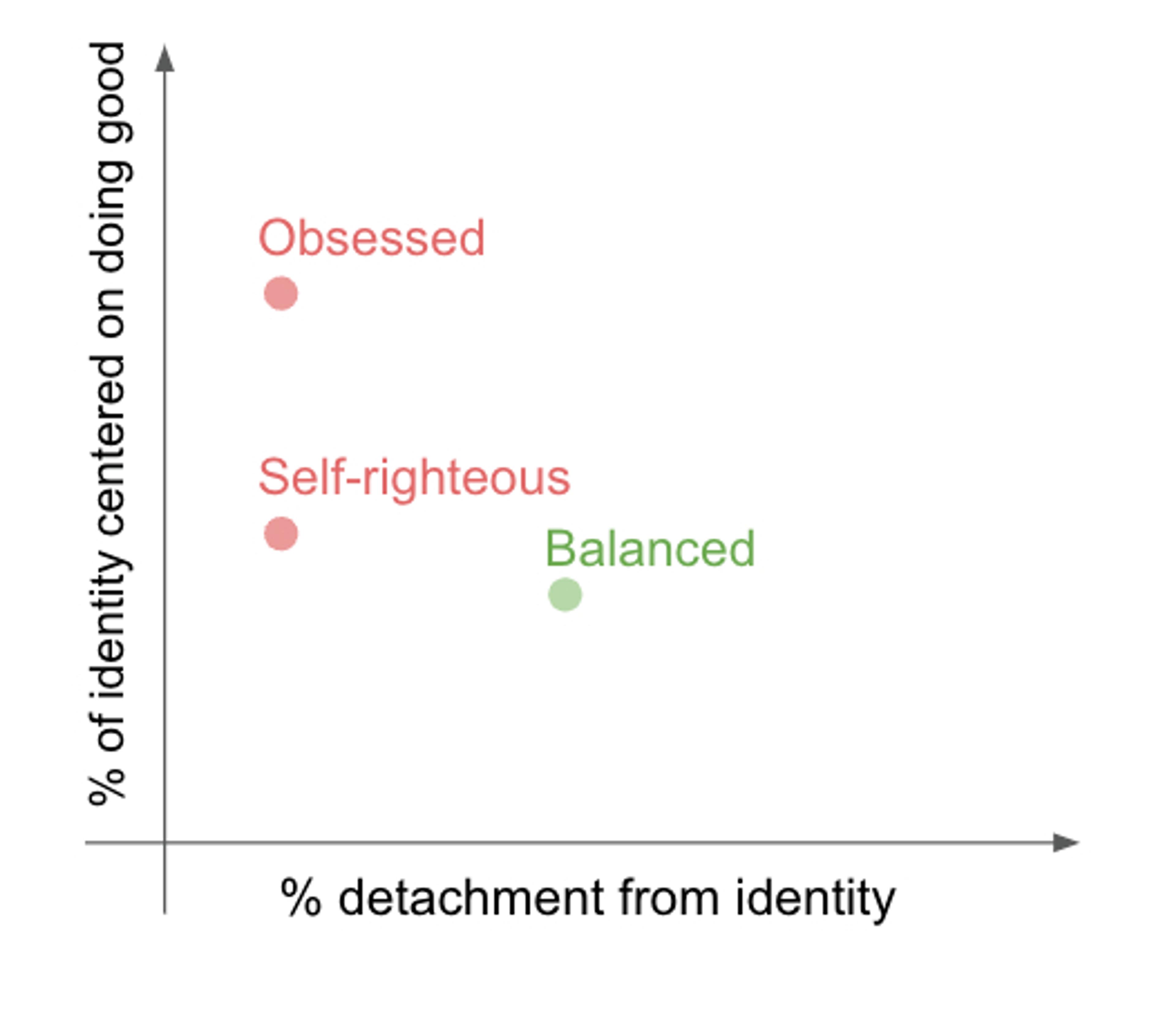

As you give more, you might find that your identity becomes more centered around doing good. Whether that is itself a desirable aim or just a side effect of focusing on doing good I’ll leave to the reader to judge. However, centering your identity around doing good can also come with a risk of becoming attached to that identity — to the story of yourself as a generous giver that saves lives — and developing a self-righteous attitude in the process. Therefore, it might be useful to separate your conceptions of what your identity centers around from how attached you are to it. You might even think of them as perpendicular quantities, as shown in the graph below:

A simple approach to detach yourself from your identity as an altruistic giver is to address the fundamental attribution error (discussed above) by acknowledging the impact that your circumstances have had on your success. How much of the money you give was really “earned” by discipline and talent? Freeing yourself from the fundamental attribution error can temper a self-righteous attitude. Another approach could be to acknowledge and joke about the hidden selfish motives of doing good and wanting to be seen as a good person (for inspiration, see the book The Elephant in the Brain), or to acknowledge other parts of your moral life and character that are less flattering. This should be done not in a self-deprecating manner but in the spirit of taking a balanced view of yourself.

To go deeper into this, you could also study the meditation practice of self-inquiry, where you look at what the “self” is, and whether any of the stories you tell yourself about the “person” you think you are are actually real. If you observe closely, you might call into question whether there is really a "giver person'' there, and you might find that there is only sensory experience arising in awareness, without any real sense of identity. You might do meditative self-inquiry: “Who is giving? Did that thought or feeling about giving originate in any ‘center’ of awareness who is the ‘giver person’, or did it just arise?” (For a more elaborate and precise description of cutting through this type of illusion of self, listen from the 33-minute mark of this episode of Sam Harris’s podcast.)

Of course, the benefits of a meditation practice cannot be experienced by reading about it. For an introduction to the practice of self-inquiry, you could begin with Adyashanti's True Meditation or Sam Harris’s Waking Up app.

However, it bears mentioning that for some people in the EA community, having a feeling of “not doing enough” might be a bigger challenge than self-righteousness. In that case, it might be relevant to explore some other approaches, like investigating whether you have unhealthy conditional assumptions regarding what is “enough”; for example, “If I don’t give at least X% of my salary, then I’m no good” — according to who? Another approach is to practice self-compassion, being less harsh with yourself. Lastly, detaching yourself from your identity might still help: If you were less attached to the identity of being an “effective altruist,” and you had less need for this self-affirmation, not living up to that identity might feel like less of a problem in the first place.

To summarize, we’ve gone through several psychological tools one can apply to support giving and doing more good. While they might not all be for you, I hope you found some of them useful. If you are interested in exploring how many lives you could save under different inputs (salary level, cost of living, stock market returns, discount rates for waiting to give, etc.), you can try my “giving optimizer” tool here.

Scientific references

- Singer, 2016: Peter Singer 2016: One World Now: The Ethics of Globalization.

- Dunn et al., 2008: Elizabeth W. Dunn, Lara B. Akin, Michael I. Norton (2008). Spending Money on Others Promotes Happiness. Science 21 March 2008: Vol. 319, Issue 5870, pp. 1687-1688.

- Dunn et al., 2014: Elizabeth W. Dunn, Lara B. Akin, Michael I. Norton (2014). Prosocial Spending and Happiness: Using Money to Benefit Others Pays Off. Current Directions in Psychological Science 2014 23:41.

- Stevenson & Wolfer, 2013: Betsey Stevenson Justin Wolfers. Subjective Well-Being and Income. American Economic Review: Papers & Proceedings 2013, 103(3): 598–604.