Maternal Nutrition - Who Pulls the Strings of Maternal Mortality

This is the second part of 'Why sometimes less is more in maternal mortality'. You can read the first part, about the safe childbirth checklist, here.

The story of food

The story of food is really the story of human kind. Many facets of the human experience have forged the development of food through the ages. For example, socio-political history: after the Second World War, Western governments vowed to end hunger, increase production and reduce the cost of food. Inevitably, science plays a deep role - fertilizers changed the landscape completely, doubling agricultural production between 1947 and 1979 [1]. Then there is fashion - take Julia Child, who singlehandedly introduced a generation of Americans to French cuisine. And let's not forget the influences of climate change, cultural differences, or the food corporate battles dictating the market. But this is not a blog post about how we shaped food. Rather, it is about how food subliminally shapes us, our health and our well-being.

The big performers on the maternal mortality stage

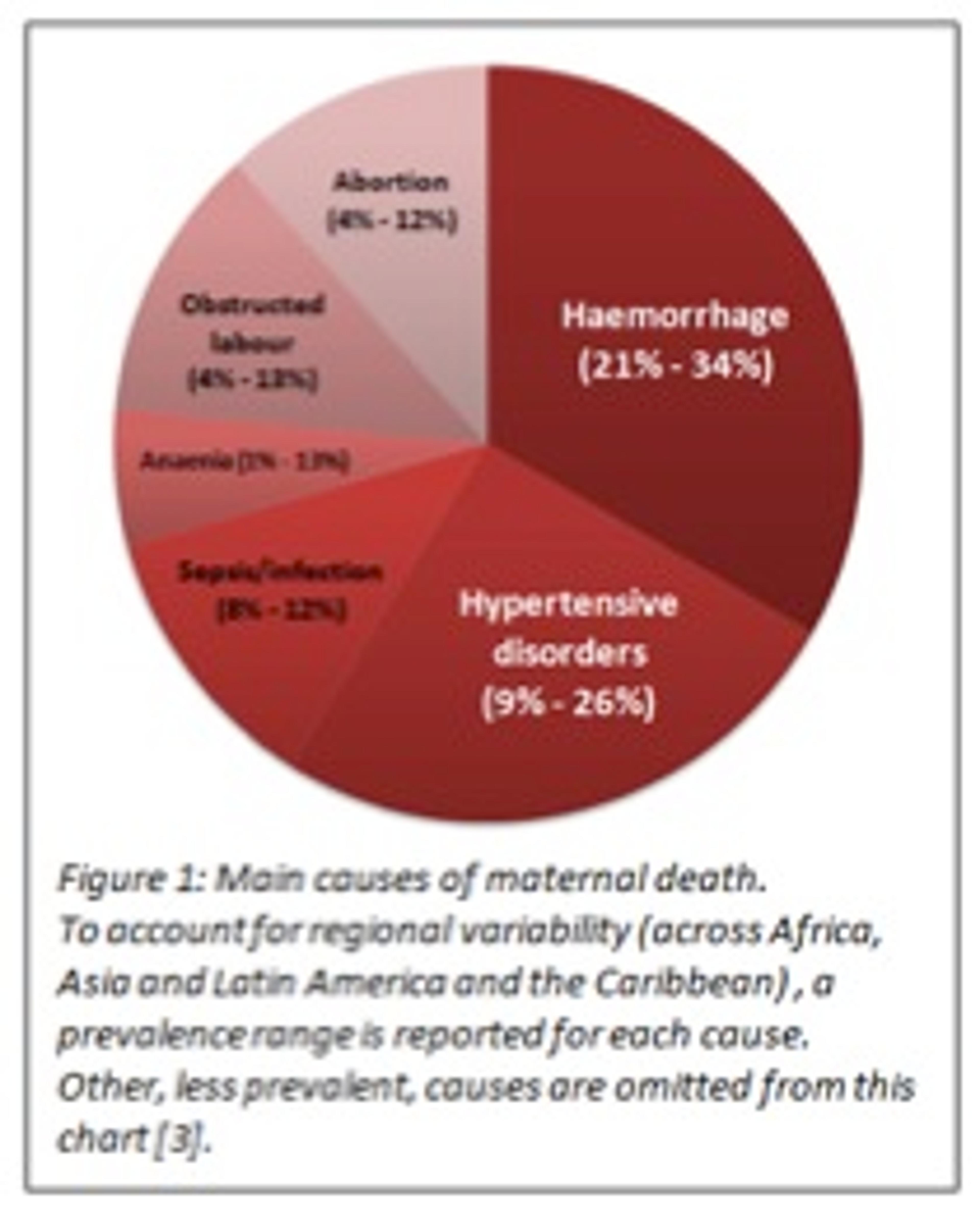

Now let me tell you another story: 800 women die every day due to often avoidable complications related to pregnancy or childbirth; 99% of these cases occur in developing countries [2]. Why does this still happen in today's day and age? In 2006, the World Health Organisation (WHO) published a strategic analysis of leading maternal death causes, accounting for regional differences (Figure 1) [3]. Which are the big players? Haemorrhage is the leading cause of deaths in Africa and Asia. Hypertensive disorders claim most maternal lives in Latin America.

Accessible and affordable interventions to counteract causes of maternal death exist. They vary in nature, cost-effectiveness and universality:

- The social category: from women's empowerment and education programmes to community groups for family planning

- The infrastructural category: from the construction and improvement of appropriate maternal health facilities to training schemes for midwives and healthcare workers

- The medical category: from screening programs for preeclampsia and hypertensive disorders to management tools and programmes for sepsis and obstructed labour.

The hidden force behind the scenes

What do these two stories - the story of food and the story of childbirth - have in common?

As cost-effective as most of the interventions mentioned above are, some of them are only scratching the surface. There appears to be a more deeply rooted cause, a hidden enemy - malnutrition. Take anaemia as an example: on its own, it is a relatively minor cause of maternal deaths (1% - 13%). However, it can be indirectly associated with as many as 50% of maternal deaths worldwide, by aggravating haemorrhage cases [4, 5]. This effect is particularly horrifying when one considers the overwhelming prevalence of iron deficiency (anaemia) which affects 30-60% of pregnant women in developing countries [6,7]. How do we fight this hidden enemy? Daily iron supplementation during pregnancy has been shown to reduce anaemia by as much as 70% [8,9]. Similarly, calcium supplementation during pregnancy has been shown to reduce incidence of hypertensive disorders: preeclampsia (a hypertensive disorder originating in pregnancy) by 55% and gestational hypertension by 35% [10, 11]. Additionally, low-dose weekly supplementation of Vitamin A or β-carotene, was seen to reduce mortality due to infection during labour by 44% [12, 13-14].

Does it really work in practice? Randomized trials have delivered compelling evidence that nutrition interventions are essential for the prevention of maternal as well as neonatal deaths [12]. Existing analysis of the cost-effectiveness of such programmes has indicated their comparable and often superior performance to other standard approaches [12, 15].

Fighting on multiple fronts

But exactly how far does the impact of malnutrition stretch? Much further than we thought...

In the last two decades, multiple studies have demonstrated the indisputable link between maternal health & nutrition and the well being of the child [16-19]. This link originates in pregnancy, where nutritional deficiencies adversely affect foetal development, resulting in low-birth weight or overweight infants and increased risk of complications during labour. But this link extends further than just these first years of life - both low-birth weight and overweight infants have been shown to be more prone to diabetes and cardiovascular disease later in life [20-21]. Nutritional interventions can improve the health of children and adults born to well-nourished mothers; they have also proven to be remarkably cost-effective in ensuring dramatic and sustained impact for little up-front investment [15,22].

Nutrition pulls the health strings of more than one generation - its effects run from maternal health, to the health of her child, and on to the adult they will become. This trans-generational passage of risk constitutes a curse as well as an opportunity - with one cost-effective intervention we can deliver multi-dimensional benefit. Nutrition is the hidden force against maternal and neonatal mortality.

Project Healthy Children, one of our recommended charities, provides nutritional solutions to communities worldwide in a cost-effective and population-contextualised way. If you would like to empower the hidden force of nutrition, fight maternal mortality and improve the health of future generations, supporting Project Healthy Children is one way to do this effectively. You can learn more about Project Healthy Children here.

References

- Somers, M. The Story of our food, Next Nature, http://www.nextnature.net/2011/08/the-story-behind-our-food/ (Accessed April 2014).

- WHO, Key facts on maternal mortality, http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs348/en/index.html (Accessed April 2014).

- Khan, K. S. et al. WHO analysis of causes of maternal death: a systematic review 2006.

- Gillespie, S. et al. Controlling iron deficiency. United Nations Administrative Committee on Coordination/Sub-Committee on Nutrition, State-of-the-Art Series Nutrition Policy Discussion, 1991 WHO.

- Galloway, R. et al., Women's perceptions of iron deficiency and anaemia prevention and control in eight developing countries, Social Science & Medicine 55 (2002) 529 - 544.

- Fifth report on the world nutrition situation: nutrition for improved development outcomes, United Nations, ACC/SCN, 2004.

- Hunt, J.M. Reversing Productivity Losses from Iron Deficiency: The Economic Case, Journal of Nutrition, 2002.

- Pena-Rosas JP et al. Daily oral iron supplementation during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012; 12: CD004736.

- WHO. Guideline: daily iron and folic acid supplementation in pregnant women. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2012.

- Hofmeyr GJ et al. Calcium supplementation during pregnancy for preventing hypertensive disorders and related problems. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010.

- Imdad A et al. Effects of calcium supplementation during pregnancy on maternal, fetal and birth outcomes. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2012; 26: 138–52.

- Rouse, D.J., Potential Cost-effectiveness of nutrition interventions to prevent adverse pregnancy outcomes in the developing world, The Journal of Nutrition, 2003.

- Sommer A,West KP Jr. Vitamin A deficiency: health, survival, and vision. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996.

- Green HN et al. Diet as a prophylactic agent against puerperal sepsis. BMJ 1931;ii:5958.

- Baltussen, R. et al. Iron Fortification and Iron Supplementation Are Cost-Effective Interventions to Reduce Iron Deficiency in Four Subregions of the World, 2004, The Journal of Nutrition 134 (10): 2678–84.

- Wijesuriya, M. et al. The Kathmandu Declaration: ‘Life Circle’ Approach to Prevention and Care of Diabetes Mellitus, 2010, Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice 87 (1): 20–26.

- Kimani-Murage, E. W. et al. The Prevalence of Stunting, Overweight and Obesity, and Metabolic Disease Risk in Rural South African Children, 2010, BMC Public Health 10 (1): 158.

- Whitaker, R. C. Predicting Preschooler Obesity at Birth: The Role of Maternal Obesity in Early Pregnancy. 2010, Pediatrics 114 (1): e29–e36.

- Bhargava, S. K. et al. Relation of Serial Changes in Childhood Body-Mass Index to Impaired Glucose Tolerance in Young Adulthood, 2004 New England Journal of Medicine 350 (9): 865–75.

- Haugen, G. et al. Fetal Liver-Sparing Cardiovascular Adaptations Linked to Mother’s Slimness and Diet. Circulation Research, 2005, 96 (1): 12–14.

- Godfrey, K. M. et al. Fetal Liver Blood Flow Distribution: Role in Human Developmental Strategy to Prioritize Fat Deposition versus Brain Development, 2012, PLoS ONE 7 (8): e41759.

- Rouse, Dwight J. Potential Cost-Effectiveness of Nutrition Interventions to Prevent Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes in the Developing World. The Journal of Nutrition 2003, 133 (5): 1640S–1644S.