Shocking images of starving children are one of the staple images of extreme poverty. But childhood malnutrition is not limited to such extreme hunger: in fact, millions of children appear normal but are chronically malnourished. The problem of hidden hunger extends widely and has got serious consequences.

The facts

Hidden hunger includes both low weight for age (excluding acute malnutrition, which cannot be considered hidden), and micronutrient deficiency, which is very often associated to low weight for age. The scale of the problem is huge: one out of six children in developing countries is underweight, that is, 100 million children in total suffer from hunger [1].

What are the consequences? To start with, 3.1 million children still die of malnutrition every year [2]. The picture is bleak: a shocking 45 [3] to 55% [4] of childhood deaths worldwide are attributable to under-nutrition. Hunger remains the biggest killer of under-five children. Furthermore, malnourished children are both more likely to contract diseases and to die from them. Of childhood deaths from disease, the following percentages can be attributed to under-nutrition [5] :

- 60.7% for diarrhoea – 800 000 children

- 52.3% for pneumonia – 1 000 000 children

- 44.8% for measles – 250 00 children

- 57.3% for malaria – 500 000 children

It is important to note that this is not limited to children who are extremely underweight. Though the effect is more pronounced in such cases, if we combine the risk associated with moderate malnutrition with its high prevalence rates, we find that much of the burden of deaths as a result of under-nutrition in young children is attributable to moderate, rather than to severe, malnutrition.

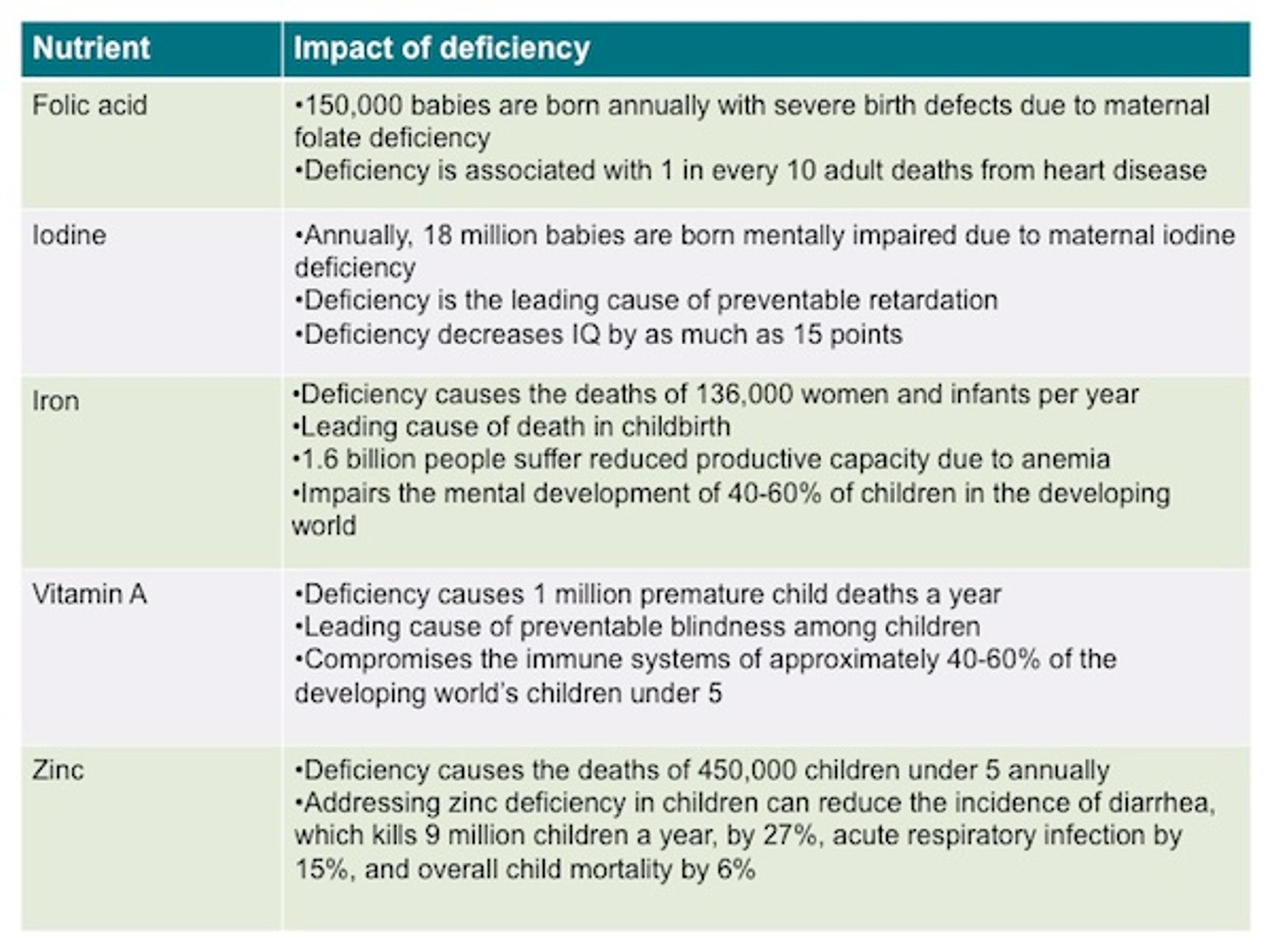

But perhaps the most invisible form of hunger is micronutrient deficiency, which, though not even necessarily associated to low body weight, can seriously reduce span and quality of life. These are some of the consequences of particular micro-nutrient deficiencies [6]:

As for the economic consequences of hunger, start by noticing that it is the main factor in causing childhood stunting, which affects a quarter of all children worldwide [7]. This has got consequences to motor and cognitive development, and to educational achievement, which in turn reduce productivity in adulthood. This and the increased health costs it causes make hunger a heavy burden on the economy. Under-nutrition and micronutrient deficiency cost up to USD2.1 trillion a year to the global economy [8], and it is estimated that childhood malnutrition costs USD25 billion a year to Africa alone [9]. In contrast, it is estimated that addressing childhood and maternal hunger worldwide would cost only USD10 million [10].

There has been some progress in reducing hunger over the last decades, with the number of undernourished people having decreases by 17% in the last two decades [11] but this is widely acknowledged to be unsatisfactory. For example, the stunting of early childhood growth as a result of malnutrition has decreased only 1% [12] in the last two decades. In comparison, TB cases have declined by 40% [13], and malaria cases by 30% [14]. Also, the improvements there have been are unevenly distributed geographically: for instance, in North Africa and South Asia the improvements have been modest, and in West Africa, the situation has actually worsened [15].

What can we do?

Solving this problem will have to involve agricultural partners, governments, and NGOs, and will likely require economic growth and improved social policy in the affected countries. As components of a solution for this problem, the following have been suggested [16]:

- create more nutrition-sensitive programmes that include small farmers and families

- increase women’s control of land ownership and farming decisions

- widen access to agricultural credit and subsidies to encourage domestic food production

- focus more on the energy supplements to pregnant women. In the Gambia, an intervention of this type lead to a 39% reduction in low birth weight cases, one of the important reasons for low body weight for age later on in childhood, and a 40% reduction in infant mortality [17].

Assessing the cost-effectiveness of interventions in these areas is possibly worth investigating. But for now the best opportunity for effective giving to target hidden hunger is micronutrient fortification, as Giving What We Can has acknowledged in recommending Project Healthy Children [18]. Adding important nutrients such as folic acid, iodine, iron, vitamin A, and zinc to staple foods is very cheap, at just a few cents per year per person, and greatly contributes to eliminating the problems caused by micronutrient deficiency. The Copenhagen Consensus has estimated that every UDS1 spent on food fortification results in USD9 benefits to the economy [19].

Micronutrient fortification is not a complete solution to the problem of hunger, but it seems to be the best place to start. The problem has a large scale and, when we consider the suffering it causes, much more should be done to alleviate it. Hidden hunger needs to be brought to light and approached integrating economic and agricultural policy, education, and large-scale health interventions like micronutrient fortification. If you want to start making a difference today, you can donate to Project Healthy Children here.

References

- WFP: Hunger Stats

- WFP: Hunger Stats

- WFP: Hunger Stats

- Undernutrition as an underlying cause of child deaths associated with diarrhoea, pneumonia, malaria, and measles

- Undernutrition as an underlying cause of child deaths associated with diarrhoea, pneumonia, malaria, and measles

- Project Health Children: Micronutrients

- WFP: Hunger Stats

- FAO: Understanding the true cost of malnutrition

- Voa News: Unicef on the cost of Africa's child malnutrition

- Evidence-based interventions for improvement of maternal and child nutrition: what can be done and at what cost?

- Project Syndicate: Finishing off hunger

- WHO: Prevalence and trends of stunting among pre-school children, 1990-2020

- WHO reports that TB rates decline

- Roll Back malaria: news

- Project Syndicate: Finishing off hunger

- Project Syndicate: Africa's hidden hunger

- What works? A review of the efficacy and effectiveness of nutrition interventions

- Project Healthy Children: Food fortification overview