WHO-CHOICE: a look at the effectiveness of different health interventions

This post is a summary of the work and results of WHO-CHOICE[1] , a World Health Organisation program designed to help decision-makers choose interventions that are cost-effective.

What is the most cost-effective way to combat malaria; distributing bed nets to 80% of a population or distributing bed nets to 50% combined with the spraying of walls with insecticide? How are public officials, faced with such problems of designing health systems, to prioritise between different combinations of interventions? How can we reduce the cost of research for developing countries that need to consider new health interventions within their existing cluster of interventions? WHO-CHOICE is a World Health Organisation program charged with helping decision-makers choose more cost effective interventions. They have published some impressive research on a wide range of health-related interventions, stretching from blindness and visual impairment to traffic injuries. Used in combination with other results, this body of research can help decision-makers prioritise more cost effective health interventions.

Designing and researching health systems

Imagine you are in charge of a country’s health authority and you want to start a new program for the vaccination of schoolchildren against polio. To know for sure what all the effects of such a program would be, you would have to compare the scenarios with and without the program. But if you decide to implement the program then you will never know what the outcome would have been had you not implemented the program. You will never know the counterfactual. The pervasive problem of not having a counterfactual has no doubt disheartened many social scientists, including myself. How are we to know the effects of an intervention if we don’t know the alternative reality in which the intervention wasn’t conducted? And what if the intervention is too complicated for robust statistical methods such as randomised control trials? How are we even to try and construct the millions of counterfactuals that would be required to analyse the set of combinations of different interventions in public health? Inevitably, policy will sometimes be a shot in the dark, but there is more reason to be optimistic than one would think.

More and more research focuses on cost effectiveness, and produces results in terms of “bang for your buck”; how many disability adjusted life years (DALYs) can be averted per dollar. Previous research has often assessed DALYs averted relative to the cost of an incremental intervention within an existing health system. An example of this would be to look at how many years of blindness can be averted by expanding trachoma antibiotics coverage from 50% to 80%. (1 DALY represents 1.67 years spent with total blindness [2] ). Comparing the result with research on other interventions would enable the decision-maker to embark on the program which promises the best health outcome.

There are a number of problems with this method:

- The effectiveness of existing interventions is not considered. It is possible that abolishing the distribution of antibiotics entirely in order to reallocate the resources into operating victims of trachoma would be more cost effective.

- The result of the research is only relevant in a setting where there already is 50% coverage of trachoma antibiotics. Other countries could not use the research since they invariably have different existing interventions, and other demographic and epidemiological characteristics.

- Following directly from the second problem, a country with already limited resources to spend on health interventions won’t be able to research the many possible health interventions available.

New methodology

To escape these methodological issues, Generalised Cost Effectiveness Analysis (GCEA) takes its starting point in a hypothetical “null” scenario where there are no existing health interventions. This may sound very theoretical, but it comes with a few advantages ( but also a few problems, which I will talk about further on). GCEA is only one of the many methodologies and tools of WHO-CHOICE. I will focus on GCEA in this blogpost. Why? Because it formed the basis of a series of interesting articles which were published in the British Medical Journal in 2012, and because it addresses the problems I outlined in the previous section. If you want the full story on GCEA methodology it is available here[3].

I should emphasise that WHO-CHOICE is a program which encompasses many people and many different tools. A typical WHO-CHOICE project would be conducted in consultation with the health ministry of a country, and aim to address the restrictions of that health system, for example, by focusing in on specific costing problems in the scaling up of vaccination coverage.

The first thing we need to recognise is that different countries have different epidemiological and demographic characteristics. These characteristics influence the outcome of a health intervention. However, when conducting GCEA, the WHO-CHOICE program divides the globe into 14 sub-regions with similar characteristics such as to make comparisons of health interventions across countries within these groups meaningful. It was noticed at an early stage that choosing the appropriate basis for the grouping of these sub-regions is one of the major challenges of the approach.

The second thing GCEA does is remove from their model all existing interventions for the countries in a sub-region. This essentially means estimating the cost-effectiveness of all existing, relevant interventions. The point is to get to a common point of reference, the “null” scenario, and then compare the cost-effectiveness of combinations of interventions to assess which diseases/issues should be prioritised to achieve the best health outcome with the available resources. More technically, GCEA is an exercise in mathematical modelling and the method allows for non-linear combination effects of different interventions. WHO-CHOICE uses a range of methods to establish the effects of existing interventions which are outside the scope of this post.

The GCEA method therefore addresses the three problems outlined above:

- GCEA considers the effectiveness of existing interventions. It is also able to consider the existing health system together with combinations of new interventions.

- The result is relevant in many settings. The cost-effectiveness of health interventions relative to the null is comparable across countries. Countries are able to consider health interventions in combination with other interventions which are specific to their country.

- This lowers the cost of research for each individual country since results are transferrable. It also helps countries to prioritise between different diseases/issues in terms of resulting benefits.

Three examples of other tools used by WHO-CHOICE are listed below. If you want to know more about these visit the WHO CHOICE page on cost-effectiveness.

- The Global Price Tags database of the costs of different types of interventions in different sub-regions. The aim has been to produce resource needs estimates for multiple countries – so called global price tags – for a number of disease and programme-specific analyses.

- The OneHealth Tool, a publicly available software. Members of WHO-CHOICE were part of the development of this software. The OneHealth Tool is a modular software which allows for program-specific costing and supports the costing, financing and national strategy development for the health sector. For example, what hospital machinery to invest in and where to place it. Country specific analyses are conducted in co-operation with health ministries and experts.

- The GeoAccess software, which models the effects of interventions depending on where they are executed geographically, and how many people have access to them. It is based on the type of optimization problem which maximises access to clean water depending on where the wells are dug in an area with clusters of people.

Results from WHO-CHOICE

The majority of the results from the many publications of WHO-CHOICE relate to specific interventions and the relative cost-effectiveness of these. It has nevertheless produced a few general conclusions. An interesting example is that countries should try to expand high-priority interventions to near-universal coverage before considering second-priority interventions on a limited scale. An example of this would be to first expand vitamin A and zinc fortification to near-universal coverage before trying to introduce breast cancer treatment (ranked primarily in terms of cost-effectiveness, but inequality and other considerations should also be made). This result comes from WHO-CHOICE’s newest publication “Making fair choices on the path to universal health coverage” (2014).

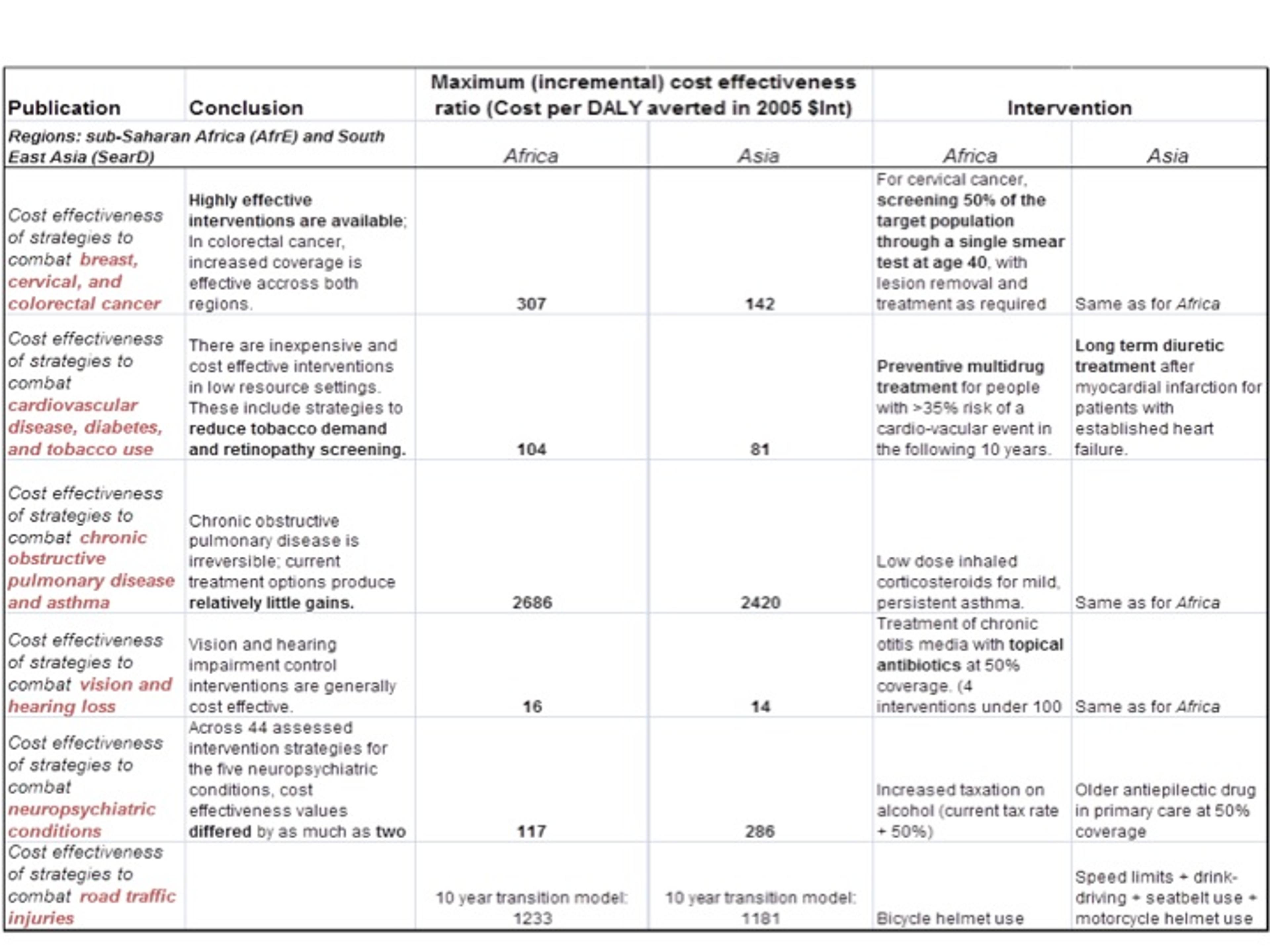

In 2012, the program published an impressive number of mathematical modelling studies in the British Medical Journal. These compared the cost-effectiveness of health interventions in sub-Saharan Africa and South East Asia. The conclusions and most cost-effective interventions of these reports can be found in the table below Please note that the interventions have not been thoroughly tested, so we should be cautious about the data and the estimates.

It is clear that the cost-effectiveness varies dramatically between different types of interventions, which is also a conclusion reached by Giving What We Can[4] . We can increase the impact of giving more than 1,000 times by choosing the most effective interventions.

The most effective intervention in both sub-Saharan Africa and South East Asia was a strategy to combat vision impairment in the form of chronic otitis. Estimates suggest that only $14 is needed to avert one DALY by distributing antibiotics with 50% coverage. This estimate is comparable with the results of the four charities that Giving What We Can recommends. However, the estimate has been reached using different methods.

Furthermore, this result should perhaps not be taken from the individual donor’s perspective, but rather from the perspective of someone who can influence the health system of that country. A previous post [5] on this blog discusses if blindness is an opportunity for effective giving. The lack of effective charities suggests that individual donors should rather look elsewhere to have confidence in finding effective donation targets.

Discussion and new directions of research

How reliable are the estimates from GCEA and how rigorous is their methodology? As you may suspect, the results of their mathematical modelling studies are not as reliable as a good randomized control trial. However, we need to remember that the research has been conducted from an entirely different perspective. It tries to estimate the effect of an intervention before it has taken place. As with economic and monetary policy, this is often an unavoidable difficulty.

I think two problems with the generalised cost effectiveness methodology are worth highlighting:

- It is not exactly clear how it asserts causality in some interventions. Mostly, a combination of expert opinion and mathematical modelling is used to reach estimates of cost effectiveness. The effects of an intervention therefore run a larger risk of being contaminated by some other event which happened simultaneously.

- Secondly, there is clearly a trade-off between making the results transferrable across countries and reliability. This ties into the problem of choosing an appropriate basis for the 14 sub-regions. WHO-CHOICE articulates this problem elegantly:

“In some sense, there is a trade-off between making CEA {cost effectiveness analysis} information precise to a given context and the time and resources required for that contextualization. Our preference for the more general use of CEA is an indication of how we see the outcome of that trade-off. We believe that the more general use of CEA, to inform sectoral debates on resource allocation, is where CEA can make the greatest contribution to health policy formulation.”[6]

In this context, it would be very interesting to see some future research on diseases not yet covered by the series published in the British Medical Journal, such as malaria, HIV/AIDS and intestinal worms. One general benefit of the WHO-CHOICE program is the identification of issues where additional spending and interventions can make a huge difference. While the individual donor should focus attention on more reliable research on specific charities, such as the ones recommended by Giving What We Can, WHO-CHOICE can help guide research into the most effective areas in the future.