Imagine an altruistic person from 200 years ago. How much good could they realistically do if they put their mind (and heart) to it?

Probably very little.

For starters, they likely lived in extreme poverty like 90% of others at the time.1 And even if they were in the top 10%, two things would stop them: they probably wouldn’t know what the biggest problems were outside of their immediate surroundings, and they probably wouldn't have any way of making progress on these problems even if they did know what they were.

Yet compared to just 200 years ago, we’ve made extraordinary progress on our ability to help others, but today’s donors often don’t take full advantage this opportunity. That’s a huge problem. Luckily, we can solve it by recognising that we’re in a better position to do good than any generation before us, and then taking action.

Today's technology gives us a unique advantage

Today, most people (who have access, mind you) take advantage of modern technology without hesitation.

It goes without saying that when we see doctors, we expect them to use medical practises that are the culmination of hundreds of years of scientific progress instead of snake oil. As a result, we now live much longer on average than people from previous generations.

When we want to reach people, we call or text them instead of sending letters that could take months to receive. Our entertainment options have also widened far beyond the limits of what past people could imagine. We have instant access to a practically endless library of high-quality music created by artists from around the globe, and it costs only a few dollars per month for a subscription. I wonder how long people in the 1800s would’ve had to save up to go to the opera, if they even liked opera music in the first place?

Much like how technology has substantially improved medicine and entertainment, it has also improved our ability to help others. Despite this, most people aren’t aware of how much technology has enabled us to make an extraordinary difference. Yet precisely because of this lack of awareness, we have an unbelievable — dare I say exciting — opportunity to do good in the world that previous generations didn’t. We just need to capitalise on it.

How far we’ve come

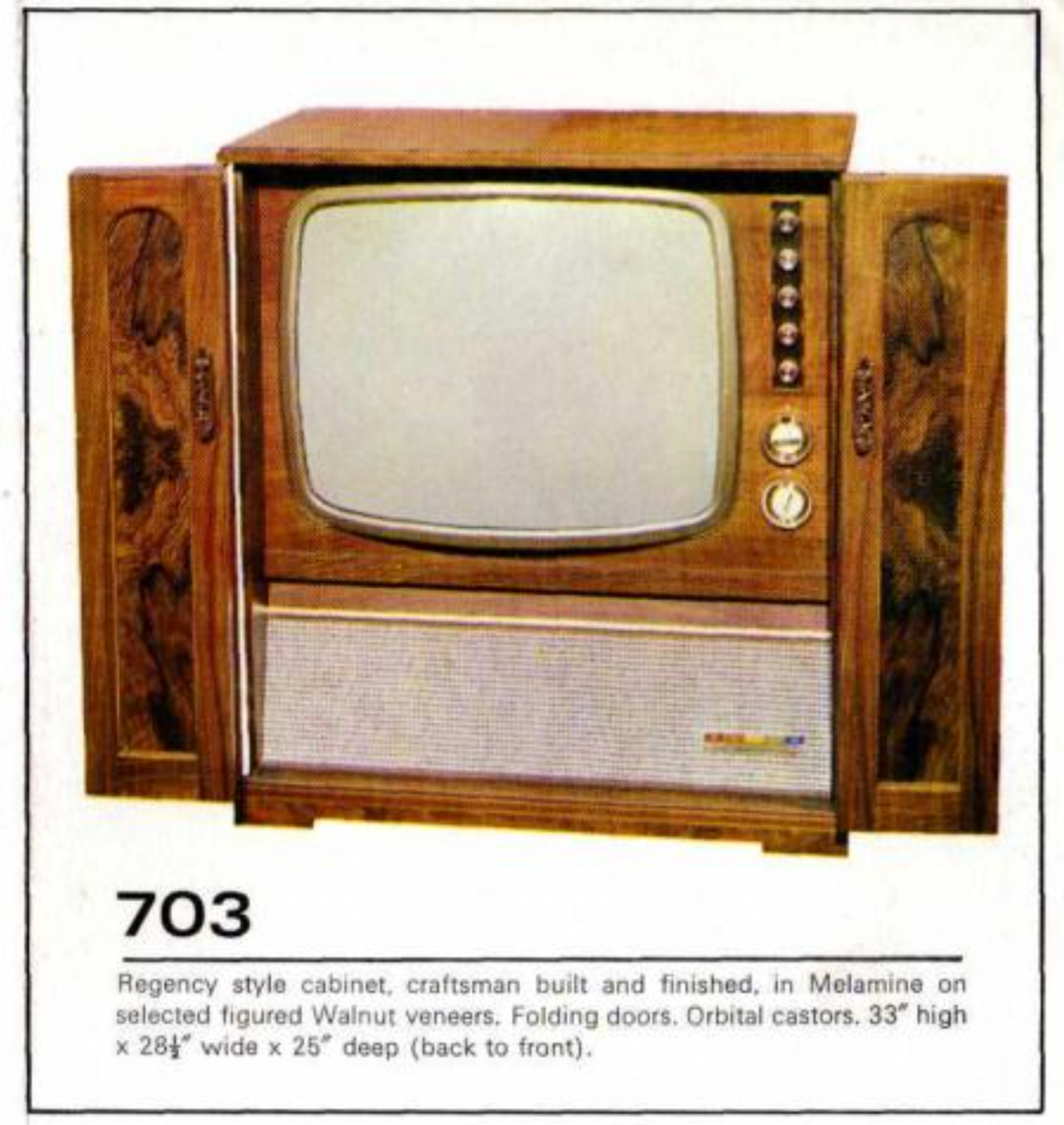

Technological progress in manufacturing and electronics has done wonders for making things cheaper, faster, better – you name it. In 1968, a Baird 703 television cost £325. That’s the same as £5,700 today when accounting for inflation. Today, it would be seen as strange to buy a clunky, black-and-white TV from the 1960s for £5,700 when flatscreens are available for a fraction of the price.

Charity is no different, though at face value it can sometimes be hard to tell. Unless we pay careful attention to how effective our donations are, it isn’t necessarily clear whether we’re donating to a charity that operates like a Baird 703 or one that operates like a 70-inch 4K LED flatscreen. It can be disappointing to think that some charities might not provide much value, but I think it can be empowering to instead think about the ones that are incredibly effective.

Focus on the flatscreens

Finding effective charities is an exciting and worthwhile pursuit, especially now that technology has made it so much easier for us to fund them. I’m constantly amazed that I can use the internet to send resources (sometimes directly to the beneficiary) around the world instantaneously and inexpensively. Thanks to the internet, I have instant access to hundreds of thousands of different charities. That is a remarkable technological achievement – imagine how envious altruists from the past would be. They would have no realistic way to send resources across the globe quickly, cheaply, and safely.

But we do. We just need to use our knowledge to take advantage of it to the fullest.

Our knowledge can open up doors

While cumulative scientific progress has taught us a lot about how to help others effectively, donors don’t always take full advantage of this knowledge. Some evidence suggests that only about 1 in 3 donors do any research before donating, and only 3% of donors give based on the relative performance of charities.

We have much better knowledge about what things work to improve peoples’ lives — or promising leads that might have huge pay-offs — than people did in the past. For example, we know that long-lasting insecticide-treated nets that prevent malaria are an effective way to save lives and improve wellbeing. Previous generations did not know this, which would’ve severely limited their ability to do much good (taking a stab in the dark, perhaps they would’ve tried medical leeches).

Of course, we know better: various charity evaluators, such as GiveWell, exist to help us figure out which opportunities to do good are the most promising. This expert knowledge is immensely valuable, and it’s sitting out in the open for free, practically begging for us to apply it. Beyond the fact that most people couldn’t read or write centuries ago, they also wouldn’t have had access to a group of professional researchers and grant-makers that meticulously comb through studies, reports, and data to find the most effective charities out there. So even if they could send money, they probably wouldn’t have any decent idea where it should go.

What’s more is that there is way more wealth around today than there was in the past. Basically everyone lived in poverty back then, so there wouldn’t have been nearly as many opportunities to improve wellbeing by donating to others.

The same cannot be said today, however.

Inequality is awful, but it gives us an opportunity

Beyond technology and knowledge, previous generations before us would be envious if they could see how prosperous our world is today. We managed to eradicate smallpox — a disease that killed an estimated 300 million people in the 20th century alone — because of our improved understanding of immunology. The share of people living in extreme poverty has plummeted. The total amount of wealth in the world has skyrocketed since the industrial revolution. Median incomes have even risen as well. Many goods that were once luxuries – think cell phones, televisions, and music players, among others – are becoming ubiquitous due to advances in computing power, manufacturing processes, and scientific knowledge. Put plainly, our world is vastly richer than it was in the past, by any measure.

Not so fast though — not everyone has felt these gains. The world might be incredibly rich, but it is also incredibly unequal. Over 600 million people still live in extreme poverty, and hundreds of thousands of children die each year from malaria, a disease we know how to prevent. Climate change poses a disproportionate threat to those who live in low-income countries.

Given substantial levels of wealth inequality between countries, people in high-income countries can often do more good by donating to people who have very little to begin with. Take for example, Burundi, a small landlocked country in sub-saharan Africa with a GDP per capita of $731. This figure already takes into account the fact that things cost less overseas. Could you live on $731 per year? I couldn’t, and it’s an injustice that millions of people have no choice but to live on that kind of income when we have the means to help them.

You might wonder: How can anyone live on such little money? Surely they’d die? And the answer is... they do. At least, they die much more regularly than those of us who live in developed countries do. Even though average life expectancy in developing countries has skyrocketed over the last few decades, in poor countries in sub-Saharan Africa it is only fifty-six years, compared to over seventy-eight years in the United States. – Will MacAskill, Doing Good Better

We can do much more good by focusing on those with little to begin with. But do we actually do that in practice? A survey of more than 6,000 donors in over 100 countries found that donors mostly support organisations located in their own countries, even if recipients in other countries would benefit significantly more from the donations. Even though we can readily help these folks, we tend to focus on problems that are nearest to us.

If the scale of this chart looks insane to you, that's because it is insane.

It seems that technology, knowledge, and wealth are necessary (but insufficient) ingredients for solving inequality and extreme poverty. These ingredients place us at a crucial moment in history; one where living conditions are awful for so many, yet one where we have the tools to radically change the state of the world for the better. To spark this change, we need to add enthusiasm to the mix.

A little enthusiasm can go a long way

The tools and knowledge needed to be impactful are right in front of us, sitting in plain sight. But without enthusiasm, we might not grab hold of them. I understand the feeling of helplessness and cynicism that can arise in light of the uncountable injustices that plague the world.

My ask is that you resist those feelings. If there’s one thing I want you to walk away from this piece with, it is a sense of optimism, paired with a conviction that you can play a bigger role in solving these pressing global problems than nearly anyone else in history.

We take its gifts for granted: newborns who will live more than eight decades, markets overflowing with food, clean water that appears with a flick of a finger and waste that disappears with another, pills that erase a painful infection, sons who are not sent off to war, daughters who can walk the streets in safety, critics of the powerful who are not jailed or shot, the world’s knowledge and culture available in a shirt pocket. But these are human accomplishments, not cosmic birthrights. ― Steven Pinker, Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress

Never before has the power to improve the world been distributed so broadly. On average, $4,500 donated to a highly effective charity can save someone’s life. This amount isn’t trivial, but it is a reasonable aspiration for many of us in high-income countries to reach (and exceed).

The person whose life could be saved will grow up to be loved by others, will love others themselves, and will have hopes and dreams that are unique only to them. A donation made to a highly effective charity can give them a chance to experience life's joys, mysteries, complexities, rewards, marvels, and quirks. It might be the best $4,500 you ever spend, and I bet altruists of the past would wish that they could have the same opportunity you do.

Drops in the bucket can feel inconsequential because of the sheer number of difficult problems the world faces. But they can mean the world to someone out there. Those very drops could be the ones that save someone’s life, or make life better in general for many. When thinking about what you should do, don't dwell too much on the daunting size of the bucket. Focus on the opportunity you have to fill it.

That opportunity excites me, and I hope it excites you too.

Next steps

If you’re excited about this opportunity, check out our:

- Giving What We Can pledge. We think that taking a giving pledge is a powerful way to commit to doing the most good you can do with the resources you have.

- Giving Guides, which answer the key questions about effective giving and include the latest effective giving recommendations so that you can do the most good with your donations across a wide range of causes.

- List of the best charities to donate to

- Recommended cause areas

- Guide on how to pick effective charities