A Brief Update on Ebola - Are There Any Effective Interventions in Sight?

The outbreak of Ebola in West Africa is the only outbreak of Ebola to this day that has taken place in a densely populated, urban environment. There is no vaccine against the horrible virus and tragically few medical options for those infected. The most effective interventions at the time of writing seem to be information campaigns and isolated treatment centres. It remains impossible to say whether these interventions are as effective as other charities recommended by Giving What We Can. Ebola may also be difficult to compare with certain other issues due to its acute and plague-like characteristics.

What is Ebola?

Ebola is a virus which is transmitted to humans from wild animals and spreads human-to-human. Monkeys, fruit bats and consumption of raw meat are a few documented sources of transmission to humans. Human-to-human transmission occurs through bodily fluids. Contact between broken skin or mucous membranes (e.g. in the nose and mouth) with an infected fluid allows the virus to enter the body and be transmitted. The average case fatality is around 50% and has varied from 25% to 90% in past outbreaks.

Past outbreaks have been limited to rural settings, but the most recent outbreak in West Africa (of a virus subtype called Zaire[1]) has affected both urban and rural areas. Since the disease can spread rapidly and has a high fatality rate, it puts a huge strain on the healthcare systems of affected countries.

Chronology and scale of current outbreak

The West African outbreak started in March 2014. 86 cases were reported by the Ministry of Health of Guinea on the 24th of March in the south-eastern part of the country. Efforts were quickly taken in cooperation with Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) to establish a treatment centre and to investigate reported cases in the neighbouring countries of Sierra Leone and Liberia.

6 cases were identified in Liberia and the Ministry of Health together with the International Red Cross (IRC) began running information campaigns. It was not until 26th May that one case of Ebola was laboratory-confirmed in Sierra Leone. The disease later spread to Nigeria at the end of July. Mali and Senegal have also reported singular cases of Ebola, but both countries succeeded in containing the disease.[2] There is currently a separate outbreak of Ebola in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), but with no cases reported since early October, the 60 MSF staff working in the local treatment centre are preparing to exit.[3]

The outbreak of Ebola in Nigeria was successfully contained even though the disease caused 8 deaths and 20 reported cases. Ebola was brought into the country by a man who travelled from Liberia by plane. This set off a chain reaction in which 19 people were infected. There was an immediate response from the Nigerian government, together with the WHO and MSF, to identify people who had been in close contact with the man, who died 5 days later in hospital.[4] The WHO declared 20 October as the end of the epidemic after 42 days without any new cases. “Strong public awareness campaigns, teamed with early engagement of traditional, religious and community leaders, also played a key role in successful containment of this outbreak.”

The table below lists the number of identified cases and fatalities per country in the West African outbreak.

| Countries | Cases | Deaths | | Guinea | 1,760 | 1,054 | | Liberia | 6,619 | 2,766 | | Nigeria | 20 | 8 | | Sierra Leone | 4,862 | 1,130 | | Senegal | 1 | 0 | | Mali | 1 | 1 | | **Total** | **13,263** | **4,959** |

Table 1 (WHO statistics as of 7 November 2014)[5]

Vaccines on trial

The response to the West African outbreak of Ebola has largely been focused on public awareness campaigns, and the setting up of treatment centres where infected people are effectively isolated. Alternative treatments such as antivirals and monoclonal antibodies are currently undergoing clinical trials in MSF treatment centres.[6]

The 2 most promising vaccines are also undergoing clinical trials, although not currently in MSF treatment centres as these trials require healthy volunteers outside treatment facilities. One volunteer in the UK has been injected with the vaccine and clinical trials are also being conducted in Mali. One of the vaccines has been developed by the Public Health Agency of Canada in Winnipeg, with the licence of commercialisation held by the American company NewLink Genetics. The other vaccine has been developed by the British company GlaxoSmithKlein (GSK) in collaboration with the UN National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.[7]

As noted by the medical director of MSF, Dr Bertrand Draguez, the two vaccines could theoretically be distributed as soon as efficacy and safety are determined. However, in practice, if mass production starts only after results from clinical trials have come out, “we could be waiting months for that product to be available in sufficiently large quantities”.[8] MSF therefore advocates the mass production of vaccines before the results of the clinical trials are known, and that a solution must be found where someone (an institution or company) accepts the risk of having to scrap the vaccine produced.

This issue has still not been resolved and is frequently debated in different forums. GSK has committed to producing 10,000 doses of the vaccine before results of trials come out. If the results are positive, the vaccine could be administered to frontline health care workers in early December. However, writing for Science magazine, Jon Cohen notes that “hundreds of thousands of doses would be needed to put a dent in the outbreak”.[9] According to Ripley Ballou, head of the Ebola vaccine program at GSK, a hundred thousand doses would take one and a half years to produce if the rate of production isn’t increased.

Effective interventions

The only available treatment of Ebola at this stage is rehydration. Efforts have therefore been focused on finding infected people, treating them in isolated treatment centres to prevent spread and providing safe burials for the deceased (the disease is at its most infectious stage after victims have died).

Public awareness campaigns have also been crucial to limit the spread of the epidemic. There are challenges to such awareness campaigns particularly in areas where there is widespread mistrust of western healthcare workers.

Below is a list of organisations that are currently accepting private donations in the fight against Ebola. MSF stands out as the most transparent and potentially most effective organisation among those listed. They have been at the forefront of information about Ebola since March 2014 and we have previously written about emergency-aid and MSF here.

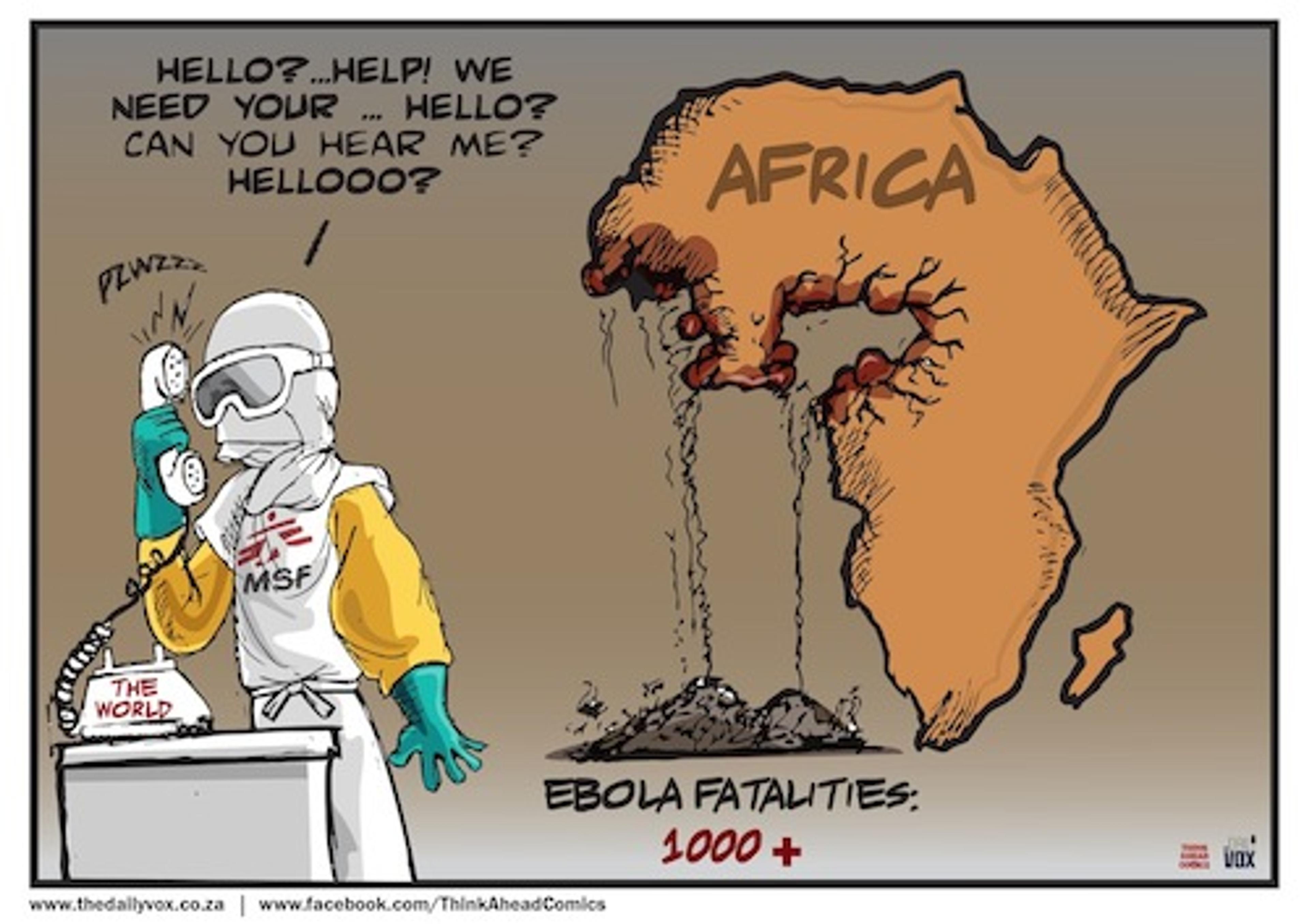

Comic by Nathi Ngubane [17]

MSF

- MSF currently runs 6 treatment centres in Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea

- They are also active with community engagement, public awareness campaigns and provide coordination and guidance to the national health authorities in the affected countries

- They have a website which is specific to their Ebola appeal where they illustrate what a donation can be used for.[10]

- In previous emergency-aid appeals such as the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, MSF have been known to close their appeal when the maximum amount needed has been reached. This prevents a waste of resources as appeals tend to overflow when western media focuses solely on one emergency or issue.

- Another reason to support MSF is their presence – MSF warned the international community about Ebola already in March, but it has been incredibly and unforgivably slow to react. MSF has a much better capacity to intervene in acute situations than other organisations, because of their presence, access to information and medical expertise. The trade-off between responsiveness and documented statistical effectiveness is debated further on Giving What We Can’s emergency-aid page.

Red Cross/Red Crescent

- Giving What We Can has previously compared the Red Cross and Red Crescent movement with MSF in its charity evaluations and concluded that MSF should be preferred when it comes to large disasters, such as Ebola. The response of the Red Cross and Red Crescent seem particularly slow in countries where they have less well-established national societies.

- The Red Cross is currently running 1 treatment centre in Sierra Leone and have 5000 volunteers working locally. Their volunteers are mainly working with public awareness, and according to their website the Red Cross can reach some areas other organisations cannot.

- The Red Cross have previously published comprehensive reviews of their interventions which contribute to transparency.

Save the children

- Save the Children’s efforts have been very similar to those of the Red Cross. They have trained 3000 volunteers who are now running public awareness campaigns, and they are running one treatment centre in Sierra Leone.

- Giving What We Can has not conducted a specific charity evaluation of Save the children. Intuitively, their work in response to the West African Ebola outbreak could be deemed as similar to that of the Red Cross. However, they do not have the same structure of reviews for different interventions.

International Medical corps

- Notably, this organisation is listed on Facebook’s Together we can stop Ebola page, together with Save the Children and the Red Cross. A look at their website suggests that the organisation is similar to MSF, but less transparent and therefore less reliable.

- They also have a smaller presence than MSF in the region, suggesting that there might be some positive scale effects of choosing MSF over the International Medical Corps.

Political advocacy for mass-production of vaccines

- This is another area in which intervention could be very effective, whilst more uncertain. Organisations working for advocacy of patent reform and cheaper access to medicines include MSF, which launched their Access Campaign shortly after receiving the Nobel Peace Prize in 1999.

MSF seems to be the best organisation fighting the spread of Ebola, and they are currently running interventions that seem cost-effective. With their longstanding commitment in the region and medical expertise it seems like that they are also the best organisation to lead efforts in the future.

Updates in the fight against Ebola will have to run continuously, particularly when the results from medical trials of the vaccines become available.

Further questions

There really is an interesting methodological issue with the effective altruist movement when it comes to emergency-aid. At least with current methods we don’t seem to be able to evaluate whether emergencies such as Ebola are the most effective causes to give to. In scale, Ebola is much smaller than, for example, Malaria. But that doesn’t necessarily mean that the marginal effect of a donation to the fight against Ebola is lower.

Another problem I would like to highlight concerns the DALY (Disability-Adjusted Life Year) measurement. If we want to compare interventions targeting different issues, then we need a measurement such as the DALY to compare the impact across causes. But it will inevitably be debatable if it is morally defensible to apply a linear weighting to diseases such as trachoma (blindness) relative to Ebola, since Ebola destroys whole communities. While this discussion is outside the scope of this blog post, it would be very interesting to see more on the topic in the future.

References

- WHO: Ebola Factsheet

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Previous Ebola Outbreaks

- MSF: 7th November Ebola Crisis Update

- WHO declares end of ebola outbreak in Nigeria

- WHO: Ebola Response Roadmap

- MSF: Vaccines and Treatments for Ebola

- WHO: Experimental Ebola Vaccines

- Science: Ebola Vaccine - Little and Late

- MSF: Vaccines and Treatments for Ebola

- MSF Emergency Appeal for Ebola

- The Daily Vox: Cartoon on Ebola