Can schistosomiasis be eliminated? Lessons from Coca-Cola and other stories.

In 2012, the World Health Assembly declared that elimination of schistosomiasis is feasible. It urged to speed up control and elimination programmes, and called on the World Health Organisation to guide member states in their efforts [1]. In line with its vision of “a world free of schistosomiasis”, the WHO put together a Schistosomiasis Plan, with the end goal to eliminate it as a public health problem by 2025, and to interrupt transmission in many areas by the same time. The Schistosomiasis Control Initiative has already carried out successful campaigns in several African countries, but there is still a while to go before complete elimination takes place. This article summarises the talk given by Dr. Michael French at the SCI 2014 Open Day, and discusses what needs to be done to eliminate schistosomiasis and what the SCI is doing to reach this goal.

Elimination of schistosomiasis

Before we continue, we need to define what exactly is meant by “elimination”. At the moment, SCI’s efforts focus on controlling the disease morbidity and eliminating it as a public health problem, i.e. reducing the prevalence below a certain threshold, say, 1%. However, to achieve true elimination, transmission of the disease within a particular area has to be interrupted. For this, the disease has to fall below the “transmission breakpoint” – at which the level of infection is so low that it will inevitably die out. Elimination is then a less ambitious goal than eradication, i.e. bringing all the worldwide cases to zero, as has already been achieved for smallpox and nearly achieved for guinea worm and polio. For the moment there is no goal to eradicate schistosomiasis. For the rest of the article we will be talking about elimination of transmission.

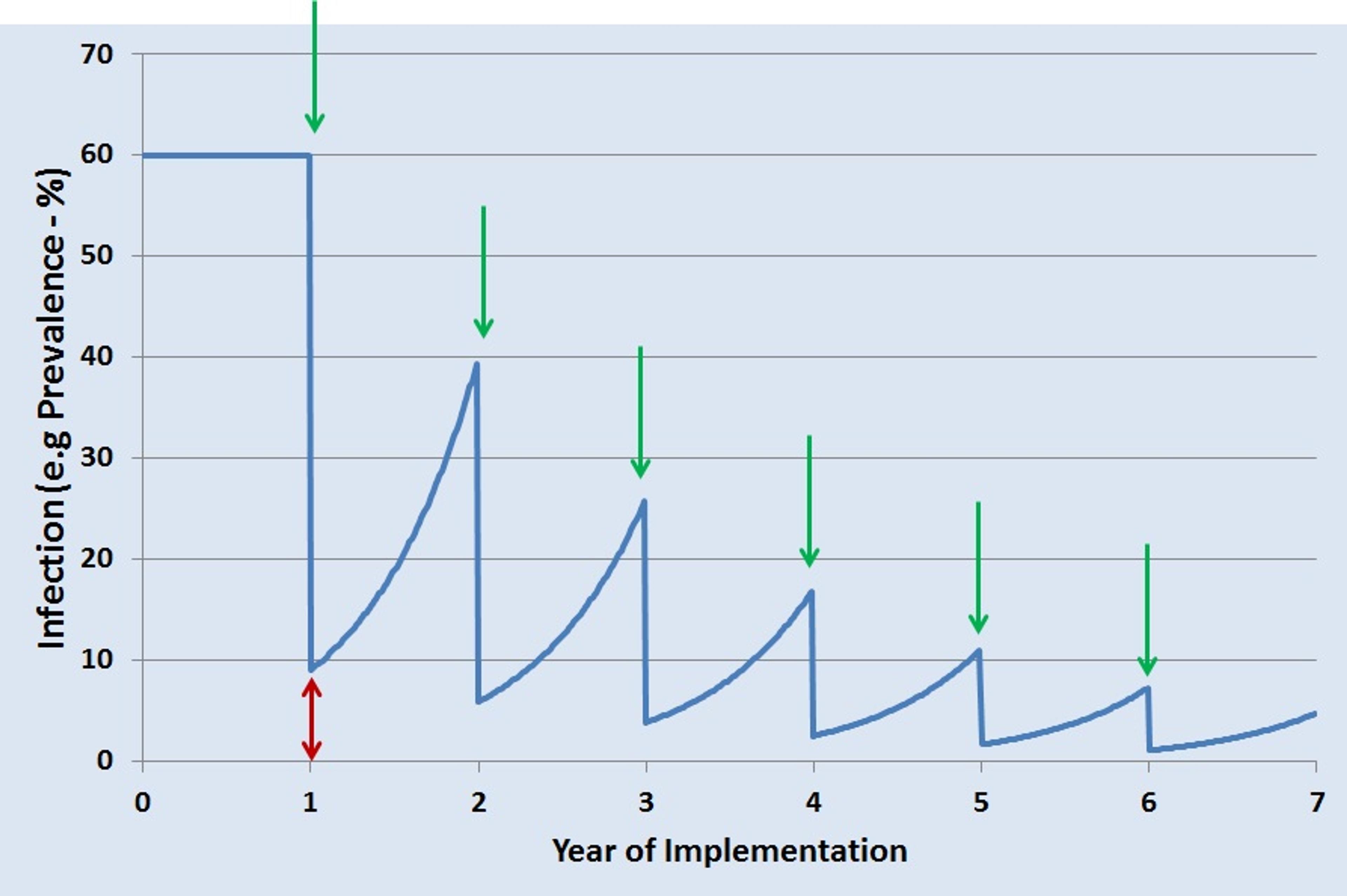

So what is necessary to achieve elimination of schistosomiasis? For its past and ongoing projects, SCI used preventative chemotherapy (PCT) with praziquantel to control disease morbidity. However, more intensive measures are needed for elimination. In areas with a high burden of disease, children as well as adults in high-risk occupations are treated every year. However, even if there is a sharp drop in infection following treatment, there is still a certain amount of infection left in the population (indicated by the red double-headed arrow in the graph), and it is enough to allow re-infection during the year. With subsequent yearly PCT, indicated by green arrows, the number of cases drops but never quite falls below the transmission breakpoint.

Prevention

What if instead it were possible to bring the infection close enough to zero from the very first round of PCT? In the long run, it would save a lot of time and resources. Because closing this gap will almost certainly require more than just PCT, a combined approach maximises the chances of interrupting transmission. For example, there are measures that could prevent infection in the first place. These include improvements in the quality of WASH (water, sanitation and hygiene), snail control (as snails are the intermediate host of the worms), behaviour change with an impact on water contact, and more novel approaches such as development of vaccines or new drugs.

To assess the effectiveness of preventative measures, work is being undertaken at Imperial College to explore the link between WASH and schistosomiasis infections. There are also randomized controlled trials carried out in Zanzibar and Burundi/Rwanda, with several arms of the trials analysing the effectiveness of snail control, enhanced treatment and improved WASH, in addition to the current chemotherapy. Another line of research is looking into vaccines. At the moment there are none commercially available, and even if the candidate compounds currently in clinical trials make it to the market, it will not be for several years. Successful vaccination depends on many factors, and the SCI are developing mathematical models to define which factors would make for optimal protection (e.g. what cross-section and proportion of the population to vaccinate, which life cycle stage of the worm to target, and the level of vaccine efficacy). All in all, these complementary approaches may help to eliminate schistosomiasis, but they are difficult to implement and in some cases not yet available.

Improving treatment

What else can be done to improve treatment? One obvious idea is just to reach more people. At the moment no population receives 100% coverage with PCT. Although drugs are in plentiful supply, with millions of doses donated every year by pharmaceutical companies, treatment can be held up by problems with shipment and transportation of drugs within the target country. To address this problem of logistics, a coalition of pharmaceutical companies, logistics companies and NGOs have formed the NTD Supply Chain Forum. The Forum’s main task is ensuring that the drugs clear through customs and reach the national warehouses on time. Another potential solution is inspired by an unlikely company - Coca-Cola. In 2009, a collaboration began that started from the simple question: if Coca-Cola can be delivered to anywhere in the world, why not life-saving medicines? A partnership between Coca-Cola, the Gates Foundation and the Global Fund resulted in Project Last Mile. The Project uses Coca-Cola’s supply chain and logistics to deliver drugs against AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria to ten African countries. At the moment it is not used for drugs against schistosomiasis, but that is an avenue to be explored.

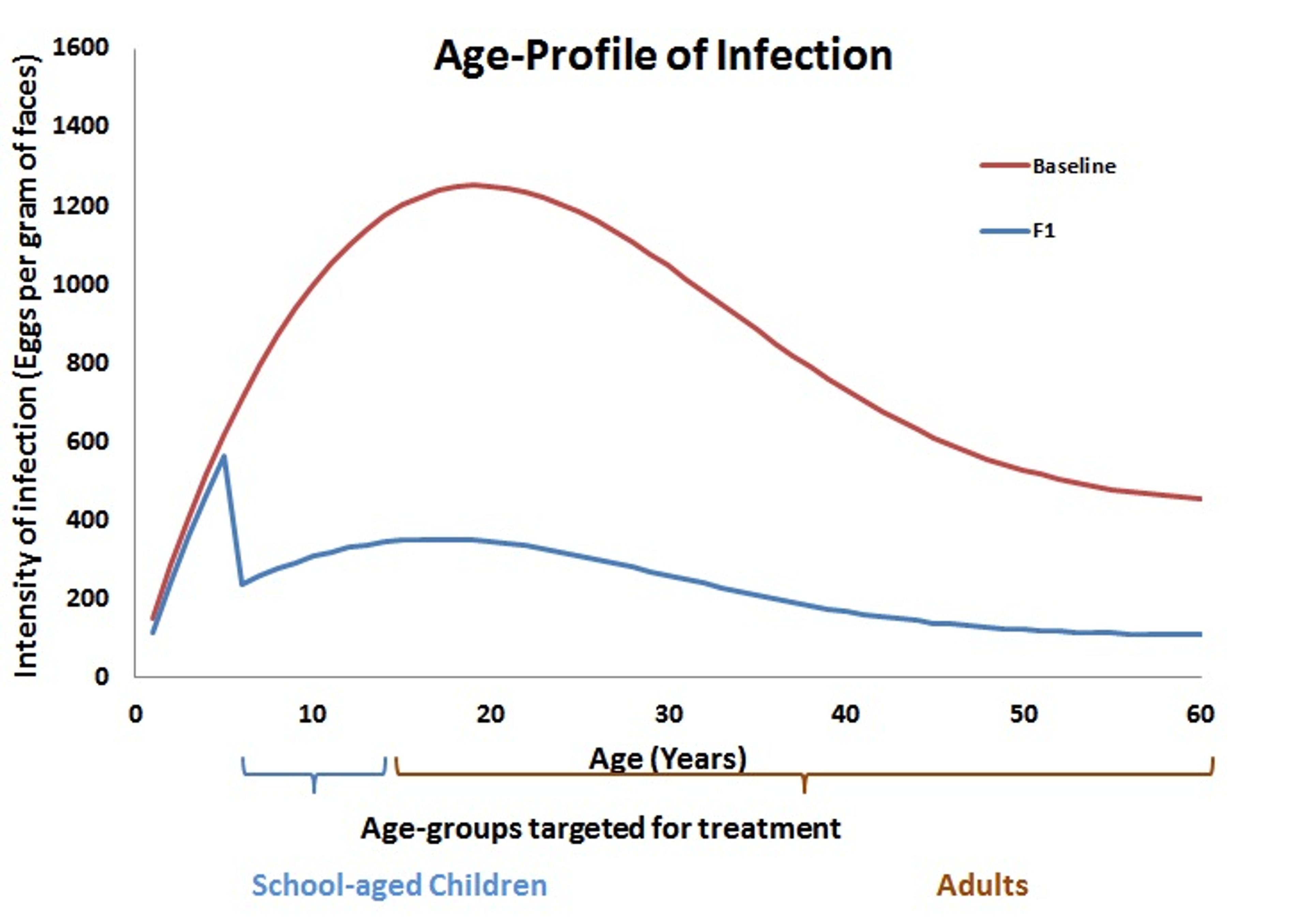

Another option is to re-consider which groups within the population receive treatment. Historically, schistosomiasis control programs have focussed particularly on school-age children, as PCT protects them from the consequences of infection later in life. Indeed, when looking at the infection profile across different age groups, the highest intensity of infection is normally in school-age children and young adults, as shown by the red “baseline” in the graph below. It is assumed that pre-school children suffer only light infection, but in fact there are very few data points to back up this assumption. By not including the very young children in the treatment group, a significant amount of infection may remain in the population. After a round of treatment (F1, blue line), the infection drops with high levels remaining only in the youngest children who were not treated. These levels, however, may be high enough to affect the rest of the population.

SCI are now researching how young children impact on worm transmission to develop better strategies to treat everyone at risk. Furthermore, a collaboration of several companies including Merck is already developing a paediatric formulation of praziquantel that could be given to pre-school children.

Conclusion

Although much progress has already been made by the SCI to combat schistosomiasis, further work requires novel approaches and a better understanding of the disease. For some types of interventions it would require collaboration with other sectors, particularly when the task is outside SCI’s area of expertise. And finally, the basics such as delivering PCT and ensuring wide treatment coverage would need to continue to a high standard, or even improved. Taken together, these approaches may finally bring us towards the elimination of schistosomiasis.

References

Slides from Dr. Michael French’s talk at the SCI Open Day 2014