Picture yourself vacationing in a developing country in the hills overlooking the coast. One day during your stay, a devastating typhoon hits, leaving hundreds of people without food, water, or shelter. Fortunately for you, you’ve not been affected by the storm. You’ve got a cozy little cottage which is high on a hill and well stocked with everything you need. The destruction on the coast has made it impossible for you to travel down the hill, but you can still help by giving money to the relief effort, which is already under way. Do you have an obligation to help?

If you’re like most people, you answered ‘yes’.

Now picture yourself sitting at home. One day, your friend, who is vacationing in a developing country in the hills overlooking the coast, calls to tell you about a devastating typhoon which has just hit, leaving hundreds of people without food, water, or shelter. Fortunately for your friend, he’s not been affected by the storm. He’s got a cozy little cottage which is high on a hill and well stocked with everything he needs. During the call, he shows you a live audiovisual stream of the destruction on the coast in real time. You can help by giving money to the relief effort, which is already under way. Do you have an obligation to help?

If you’re like most people, you answered ‘no’.

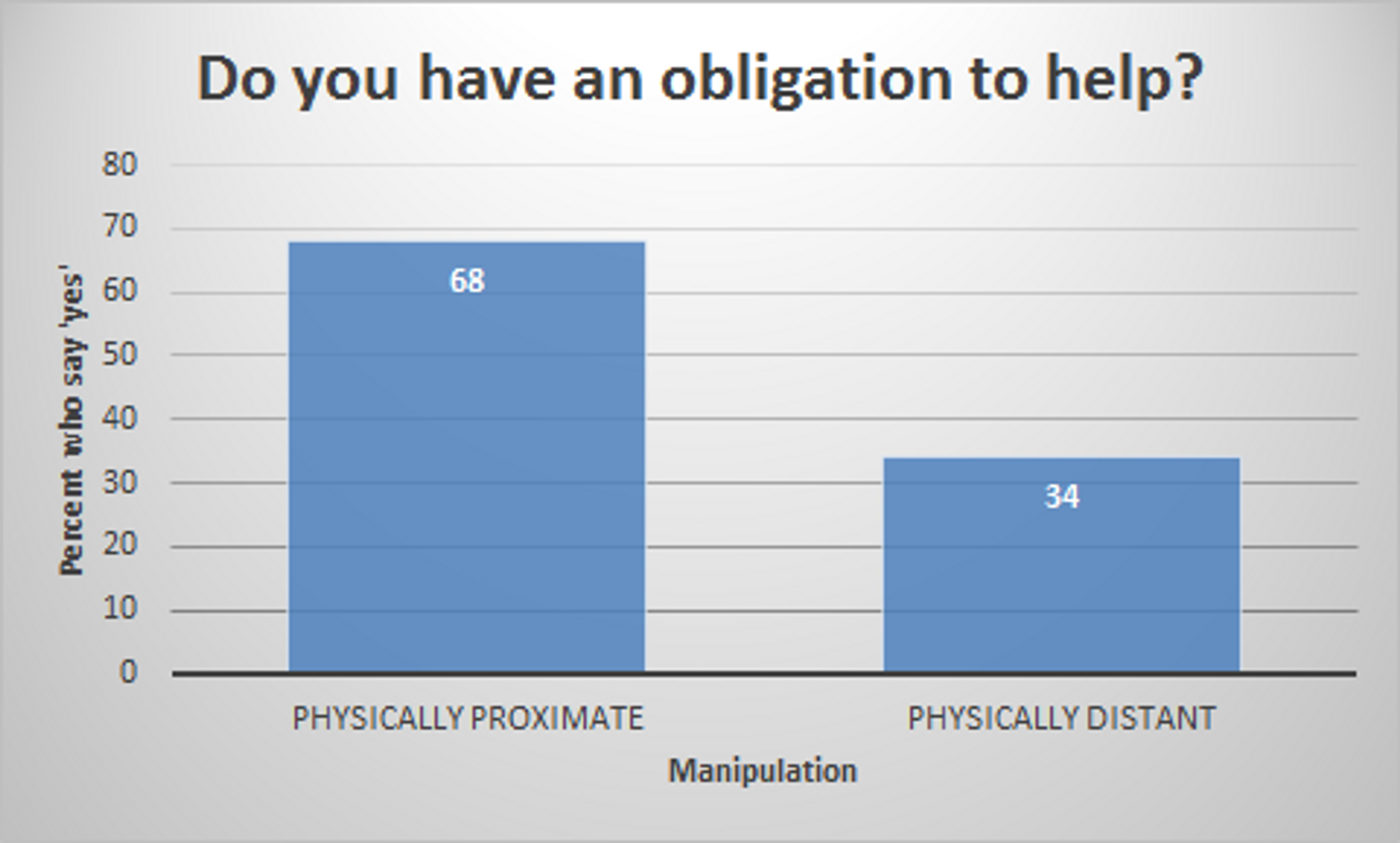

Why? In both scenarios, these villagers are not assumed to be your friends, relatives, or community members. In both scenarios, the villagers are equally in need of your help, and you are equally capable of helping. In both scenarios, there are just as many other people who can help in the same way you can. And yet, twice as many people believe that they would be morally obligated to help in the former scenario compared with the latter[1].

The only salient difference between these two vignettes is one of physical proximity. In the first case, the villagers are suffering near to you, and in the second, they are suffering far away. This experiment demonstrates an important feature of our psychology: People who are physically distant appear less morally important.

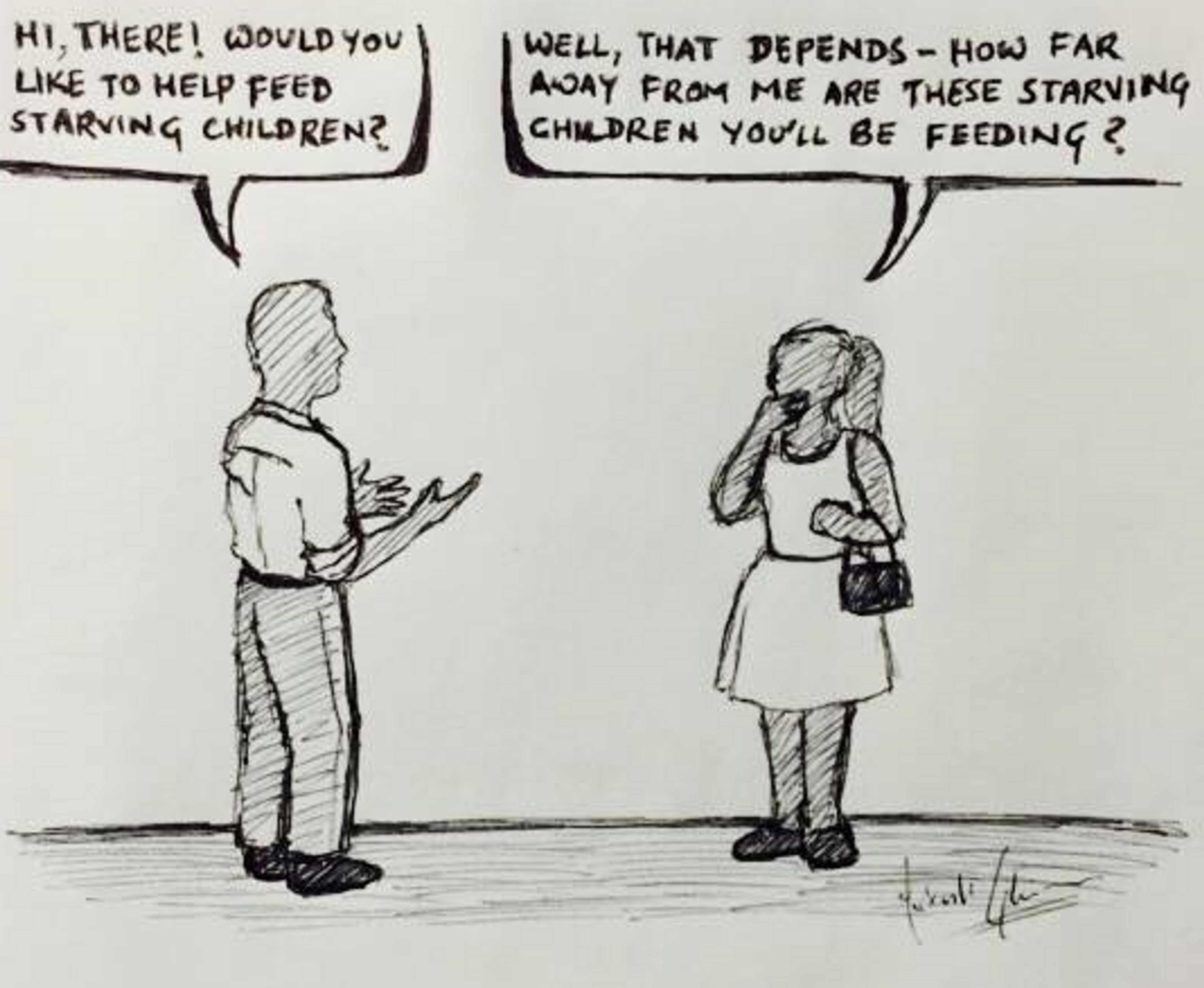

Intuitively, physical proximity matters. But should physical proximity matter? Our responses to these two scenarios demonstrate a cognitive bias, in the sense that geographic displacement is not the sort of thing we think we should care about when we give it a moment’s thought. For instance, imagine that a charity solicitor asks you for a donation to, say, feed starving children. It would be quite odd, to put it mildly, if you responded with, ‘Well, that depends. How far away from me are these children you’ll be feeding?’ This just doesn’t strike us as an appropriate question to ask.

[2]

At first, the physical proximity bias might seem like merely a curious feature of our psychology - that is, until you recognize the enormous amount of human misery for which it is responsible. Since you began reading this article, a child has died from malaria. By the end of this year, more than half a million children will have died from malaria[3]. These tragedies are entirely and easily preventable by the actions of those in the developed world. At the individual level, already 1,000 people have pledged at least ten percent of their income to fighting malaria and other causes of extreme poverty with Giving What We Can. If another 100,000 followed suit, we could eradicate malaria in the next fifteen years[4]. At the government level, the same feat could be accomplished for just 0.2% of the annual US federal budget[5].

Why aren’t we doing this? A large part of it has to do with the fact that children don’t die from malaria where we live. They die far away, in Africa, where their suffering and the suffering of their mothers and fathers seems unimportant. Never mind their nationality - if hundreds of thousands of children under the age of five were dying in the US, we would find 100,000 people willing to donate to help them. We would increase the federal budget by 0.2% to help them. But instead, these children live thousands of miles away from us, and so we don’t experience the same level of empathy that would otherwise drive us to save them. This is the power of the physical proximity bias.

The Problem with Altruism

People perform acts of altruism every day. When I talk about ‘altruism’ in this context, I’m not talking about acts of kindness towards family, friends, or community members. The sort of altruism I’m interested in involves some personal sacrifice for the sake of people you will probably never know or even have the chance to meet. This could be anything from holding the door for a stranger to donating a substantial portion of your personal wealth to charity. But there are many problems with our altruistic behavior. And there is no more stark an illustration of these problems than the fact that we in the developed world will continue to allow hundreds of thousands of children die from malaria despite it being well within our power to save them.

Already I’ve alluded to my diagnosis of the root cause of these problems - our failure to notice and overcome moral biases. Physical proximity is just one of a host of obviously morally unimportant factors which nevertheless influence our altruistic behavior. Other examples include the race and country of origin of those in need. Presumably, the goal of our altruistic behavior is not to help those who happen to be close to us, or who happen to be of the same race or to have been born in the same country as us. Take a moment to think about what the purpose of altruism actually is. The answers will vary somewhat based on cultural differences, but almost everyone tends to converge on a single, core ideal - to improve the lives of conscious creatures by as much as you possibly can.

When you first hear this, it seems like a strikingly obvious idea. For example, if I donate $100 to charity, and I have the choice between donating to a charity which can save 2 children from starvation or 20 children from starvation, I ought to choose to save the 20. This intuition is shared almost universally. As Joshua Greene - a leading researcher of moral psychology at Harvard - once told me, never has he run an experiment in which a subject said anything like, ‘Saving more lives? Why would I want to do that?’.

The reality is that we are faced with these choices all the time. Every dollar we donate to charity, or that our governments spend on the public good, can do more or less to improve the lives of conscious creatures depending on how it’s spent. However, when helping others, the question of how much good our money is going to do often doesn’t cross our minds. We see people in need, feel a strong visceral desire to help, and donate to the cause. End of moral calculus. Rarely do we ask ourselves how much good the same amount of money could have done had we donated it to, say, the Against Malaria Foundation, ranked as the most effective charity in the world by GiveWell.

At present, most people are ineffective altruists, whose generosity is at the whim of moral biases, and whose kindness ends up giving less help to fewer people than it otherwise could. The problem is not that resources are too scarce. We’ll have enough food, water, and energy to sustain humanity for the foreseeable future[6]. The problem is not even that we need to give more. Private contributors in the US alone donate enough money end extreme poverty[7]. The problem is that we need to give more effectively.

In the domain of morality, objective thinking saves lives. So how can we learn to make altruistic decisions more objectively? Before answering this question directly in my next post, I want to draw an analogy between how we think about morality and how we think about economics. When it comes to altruism, our objective - or at least, one of our most important objectives - should be to improve the lives of conscious creatures to the greatest extent that we can. When it comes to economics, our objective is to increase our personal wealth to the greatest extent that we can. Both are plagued by myopic cognitive biases, which impede our ability to achieve these aims. But the two domains are strongly disanalogous in that, in the case of economics, we have largely learned to identify and triumph over our biases. Perhaps the methods by which we’ve overcome our economic biases can overcome our moral biases as well.

References

- Musen, Jay. "Moral Psychology to Help Those in Need." Thesis. Harvard University, 2010. Print., as described in Greene, Joshua David. Moral Tribes: Emotion, Reason, and the Gap between Us and Them. New York: Penguin, 2013. Print.

- Cartoon courtesy of Mukesh Ghimire

- World Health Organization. "Malaria." WHO. N.p., Apr. 2015. Web. 20 Apr. 2015.

- Zelman 2014 (Zelman B, Kiszewski A, Cotter C, Liu J (2014) Costs of Eliminating Malaria and the Impact of the Global Fund in 34 Countries. PLoS ONE 9(12): e115714. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0115714) predicts $8.5 billion will be needed over the next 15 years to eliminate malaria. Calculations assume those pledging 10% of their income have an average yearly nominal income of $50,000, which is fairly typical in developed nations.

- The US federal budget in 2015 is $3.9 trillion (National Priorities Project. "Federal Spending: Where Does the Money Go." National Priorities Project. N.p., n.d. Web. 23 Apr. 2015., “Federal Spending”).

- Armstrong, Stuart. "Water, Food, or Energy: We Won't Lack Them." Practical Ethics. University of Oxford, 22 Nov. 2011. Web. 23 Apr. 2015.

- Giving USA 2014 (Giving USA. "Annual Report on Philanthropy." Lilly Family School of Philanthropy, 2014. Web. 23 Apr. 2015. ) reports that private contributions from US donors amounted to $335 billion in 2013. Extreme poverty is defined as living on less than $1.50 a day - which 1.2 billion people now do. Assuming their income is normally distributed, we could simply give them enough money to put them above the extreme poverty line for $330 billion annually.