The Failures of Foreign Aid (and some potential solutions) Part 2

The Politicization of Aid

So even if our aid was solely focused on the Millenium Development Goals, it still would fail because it is simply not large enough. However, Peter Singer does spend some of his chapter arguing that the way America picks its foreign aid targets isn’t really all about aid. Instead, it’s all about… politics.

Who Benefits

During the Cold War, the politics of aid was at its height — money was spent on other countries not to reduce poverty or fight disease, but rather to tilt countries away from Soviet influence. Peter Singer writes about hundreds of millions of dollars that was given directly to a Congolese dictator, all of which was included in Easterly’s $2.3 trillion figure. Obviously, those hundreds of millions did little to help meet the Millenium Development Goals. The fact that this spending did nothing to help people in poverty is no evidence at all for the criticism of aid that is sincerely directed at eliminating poverty.

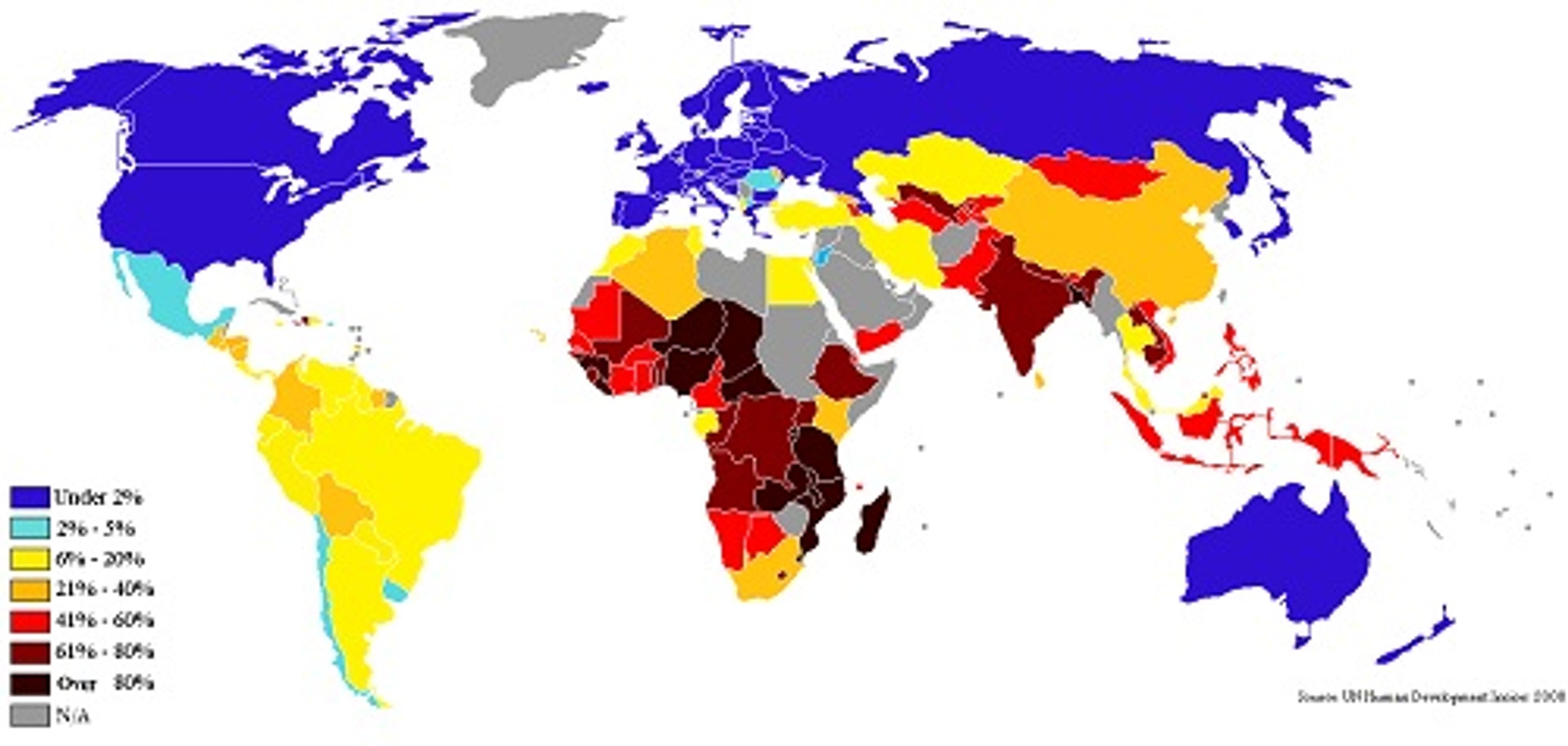

Likewise, in 2011, Afghanistan, Israel, Iraq, Pakistan, Egypt and Afghanistan received $21.3B of the $32B in US aid, or 66.3% of the total aid budget. Again, it’s clear that these nations are the target of aid not because they are the most poor or most in need, but because — even though they have more than a fair share of legitimate humanitarian problems — they are key countries in the War on Terror. It’s no coincidence that all these nations are near or in the Middle East.

Now, the point that Peter Singer and I are making is not that it’s necessarily for nations to offer aid to achieve political goals. It’s just to point out that such politically motivated aid should not be criticized for failing to achieve humanitarian goals — because humanitarian goals are just not what we have in mind. Less than 5% of aid spending is on health -- things like “twelve cent medications” are funded much less frequently than Easterly seems to claim. And that’s something we need to own up to. The humanitarian goals need more work, and they won’t be achieve with the kind of spending we currently have.

How They’re Benefitted

Another political problem with US foreign aid that Singer points out is that our aid is focused on indirectly benefitting the US. Congress requires that US aid be in the form of US goods transported on US ships. A government agency that intends to stop the spread of AIDS in Africa by distributing condoms must buy these condoms from American manufacturers and load them onto American ships — even though this would cost more than twice as much as doing the same with Asian manufacturers and Asian ships, or by building the necessary industries in Africa and using those industries to employ Africans themselves.

It gets worse when you consider food aid. Politics requires that food aid be in the form of government subsidized US goods shipped on US ships. This results in food being dumped in Africa at great shipping expense and displacing the local market, resulting in less income for African farmers. The need to transport food from far away also delays the arrival of urgently needed supplies. Furthermore, as 70% of the cost of aid is tied up in shipping and logistic costs, changing the system could allow for nearly three times more aid per dollar.

Instead, the same corn could have been bought in Africa without shipping costs and other overhead costs, providing income directly to African farmers instead of taking it away from them. While a boost to American business, inefficient regulations like these can mean that spending $27 billion a year is often the equivalent of $7 billion a year or less. While these regulations help a few specific American businesses, in particular shipping, they require higher taxes for everyone else to fund unnecessarily expensive programs. When economic and political goals are substituted in place of humanitarian goals, its no wonder the humanitarian goals suffer.

Corruption, Dependence, Institutions, and Millennium Villages

While Singer points out that aid is insufficient at cutting extreme poverty, extreme hunger, and disease because it is (1) too small, (2) badly directed, and (3) badly structured, he also argues that aid critics go too far by suggesting that all aid is caught up by corrupt governments and/or that it just creates dependency. The reason for this is that it is ignorant of how aid actually works.

Sure, giving money directly to the poor might breed dependency (though some results suggest otherwise) and giving money directly to certain governments might enrich only their corrupt leaders. That’s why foreign aid money is mostly neither given directly to the people or the government (though a lot of money in the past certainly was, which is more reason why Easterly’s $2.3 trillion over fifty years figure failed to eradicate poverty).

As an example of effective foreign aid, Singer points us to the United Nations Millenium Villages Project. This was a project to provide simple interventions to put extremely poor people on paths to sustainable growth that would continue even after the Millenium Villages Project stopped. Some of these interventions involve the creation of village-run institutions to decide how aid is spent that must involve the input of women, programmes to purify drinking water, vitamin and mineral supplements, immunization, bed nets to prevent malaria, new technology like stoves and energy production, and deworming to rid people of internal parasites.

Another example programme Singer mentions is offering fertilizer and better seeds to farmers that will improve their agricultural productivity, and farmers in return are required to give a portion of their increased harvest to a programme that would feed school-children — continuing the cycle to improve nourishment and school attendance. The project makes sure to require village buy-in, focuses on the long-run, focuses on changing things at the institution-level, and works to create sustainable change. It’s very different from the drop money and run approach that would create dependency and corruption.

Conclusions

Singer points to several failures in foreign aid with humanitarian goals — not enough money is being spent, and the money that is being spent is not on the countries that need it the most or on the most effective methods. Instead, too little money is being spent on wildly ineffective measures. Yet, Singer offers foreign aid a way out to meet its humanitarian mission: work on funding more proven interventions at much higher rates, and end the counterproductive regulations and food subsidies.

Singer, being consistent with a more politically liberal tradition, even suggests an easy place foreign aid money could come from: slightly higher taxes. Consider the proposed Millionaires’ Tax, a 5.4% additional tax on all incomes over a million dollars in the US.

The Joint Committee on Taxation has estimated this would bring in roughly an extra $42 billion per year, which combined with the current aid budget would be enough to fully fund the Millenium Development Goals with an extra $9 billion annually left over. Another way to get the $60 billion per year would be to just cut the US Defense Budget by 10%. A large share of this money (something like $20 billion) could immediately be raised just by redirecting US Aid’s funding from politically oriented projects, towards development projects.

Now, I don’t suggest that any of these specific changes would be wise — I just do this to suggest that making very serious and significant strides toward eliminating extreme poverty, extreme hunger, and disease is possible, with equally serious and significant changes in our priorities. Remember that $60 billion annually is a simple $200 per person per year in the United States. Such an amount is hardly out of our reach.