I recently completed my half marathon raising £755.18 for the Schistosomiasis Control Initiative (SCI). This is enough to protect over 1,400 children from the life-destroying effects of 4 neglected tropical diseases (NTDs).

What does this mean for the individuals with schistosomiasis or intestinal worms? Who are the people that these donations will help?

Madagascar, an island off the coast of Southeast Africa, is one country that receives funds like those from my half marathon. Madagascar is known for its incredible wildlife, 80% of which is found nowhere else in the world, but less well known is that an estimated 92% of Malagasy live on less than $2 per day (World Bank). Madagascar has only recently started to receive some international aid after a political crisis in 2009 left the country isolated.

With such a high percentage of the population living below the poverty line, it is not surprising that Madagascar is endemic for five NTDs. Millions of children and adults have gone untreated for years. Up to 90% of school-age children were found to have at least one NTD.

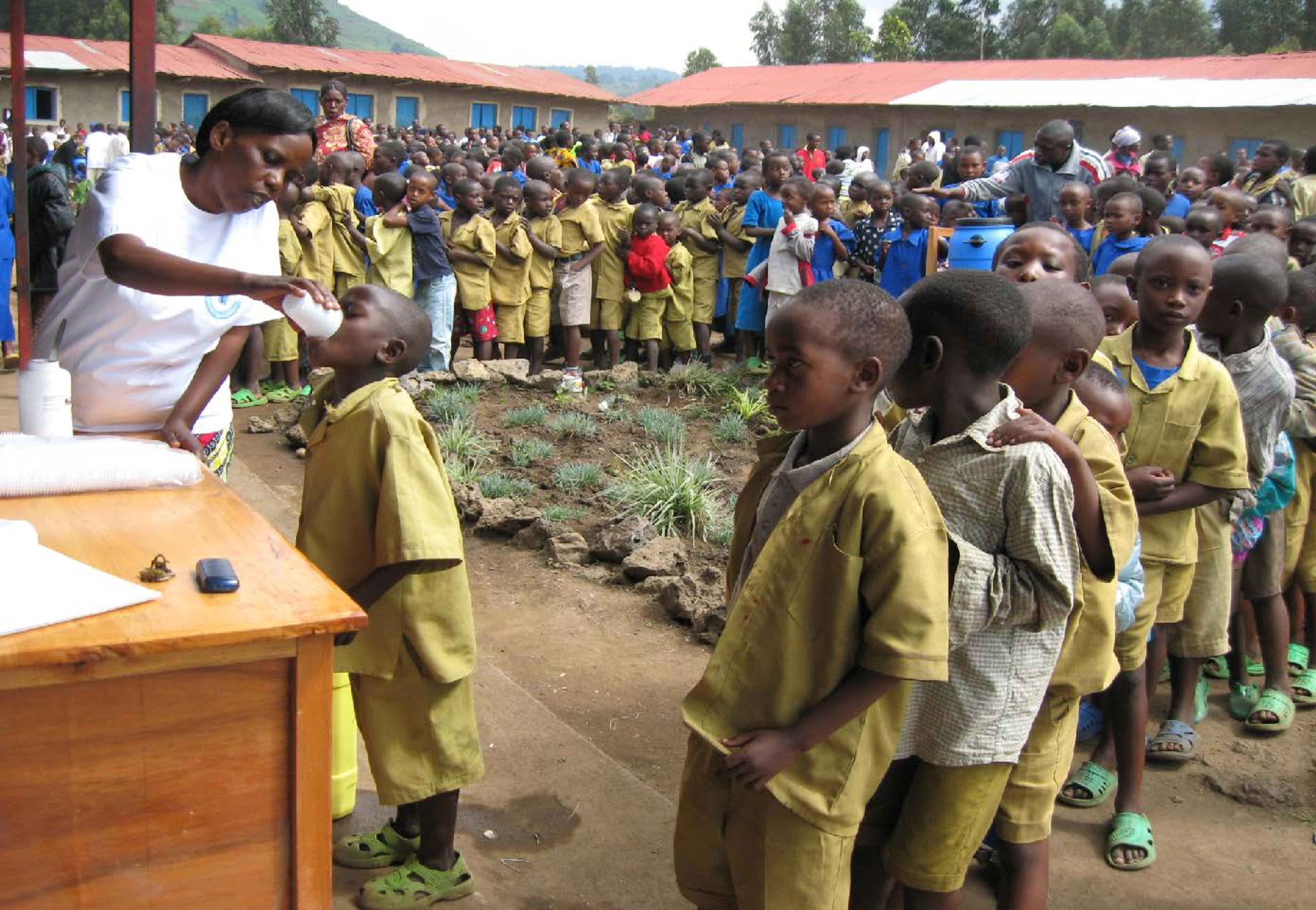

The SCI is assisting the Ministry of Public Health (MoH) and the Ministry of Education (MoE) in Madagascar to develop and deliver a comprehensive and robust national treatment programme for school-age children. SCI assists in the training of teachers, community health workers and officials to provide treatment against schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminths (STH). Working together they develop appropriate targeted materials to promote treatment in the community (e.g. flyers, posters, story books, radio and local meetings),and try and reach as many adults and children as possible, both in and out of school.

It is challenging work.

Madagascar is a large island with poor infrastructure, which means that reaching more remote communities might only be possible by boat or ox driven cart. This makes the delivery of treatment to the more remote villages even more remarkable.

Interviews provided by the Schistosomiasis Control Initiative

Fourteen-year-old Jean-Baptiste Lala lives with his mother and five siblings in one such small village in rural Madagascar. Like so many boys his age he loves playing football, although they do not even have a ball where he lives.

Jean-Baptiste dreams of going to school to become a teacher, but sadly he missed school a lot recently because of stomach aches and tiredness. His mother said he gradually lost weight and even the usual interest he had in friends and school. “He just sleeps all day”, she says. Jean-Baptiste and his friends often play in a lake infested with schistosome larvae, and have no access to clean water. It’s not surprising that so many children like him and his friends become infected.

Thanks to support from the SCI, the MoH and MoE’s National Schistosomiasis and STH Control Programme are able to reach villages like Jean-Baptiste’s. A group of specialists and technicians assessed him and his friends along with the other children in the village. They found that his bloody urine contains hundreds of schistosome eggs, and that other children were infected with intestinal worms. This is the case for many other children in the village, and free treatment will be provided.

Elodia Razanadakoto, a teacher in Jean-Baptiste’s village said,“so many children were infected with schistosomiasis that it was simply considered normal to have blood in your urine.”

If Madagascar and the SCI receive enough financial resources, the National Schistosomiasis Control Programme will be able to continue delivering treatments to millions of children like Jean-Baptiste and his friends, so that they can stay well, go to school and achieve their childhood dreams.

At the moment, the MoH, MoE and the SCI only have enough resources to be able to roll out treatment for some children. With more funding they will be able to achieve national coverage, ensuring all children and adults at risk receive the life changing treatment they so desperately need. The physical effects of NTDs prevent children from going to school and fulfilling their potential, trapping them in poverty. Adults can lose their livelihoods and ability to provide for their families.

Maria Floricia Razafirondra is a young nurse. Her mother got schistosomiasis working in the rice fields where their irrigation systems can harbour schistosomiasis-infected snails. Madagascar consumes more rice per capita than any other nation in the world. While Maria’s mother was very lucky to receive treatment for schistosomiasis, she no longer works in the rice fields because she is likely to be infected again. If she had access to regular treatment she could regain her livelihood.

The SCI is consistently ranked one of the most cost-effective charities you can donate to. A donation of just £10 would facilitate a year’s worth of treatment for twenty people. But that’s not just a fantastic statistic, the knock-on effects are huge. £10 translates into twenty people like Maria’s mother, able to work and feed their families. £10 translates into twenty children like Jean-Baptiste and his friends, regaining their energy, doing well at school and getting one step closer to a bright future.