Maternal Mortality

Giving What We Can no longer conducts our own research into charities and cause areas. Instead, we're relying on the work of organisations including J-PAL, GiveWell, and the Open Philanthropy Project, which are in a better position to provide more comprehensive research coverage.

These research reports represent our thinking as of late 2016, and much of the information will be relevant for making decisions about how to donate as effectively as possible. However we are not updating them and the information may therefore be out of date.

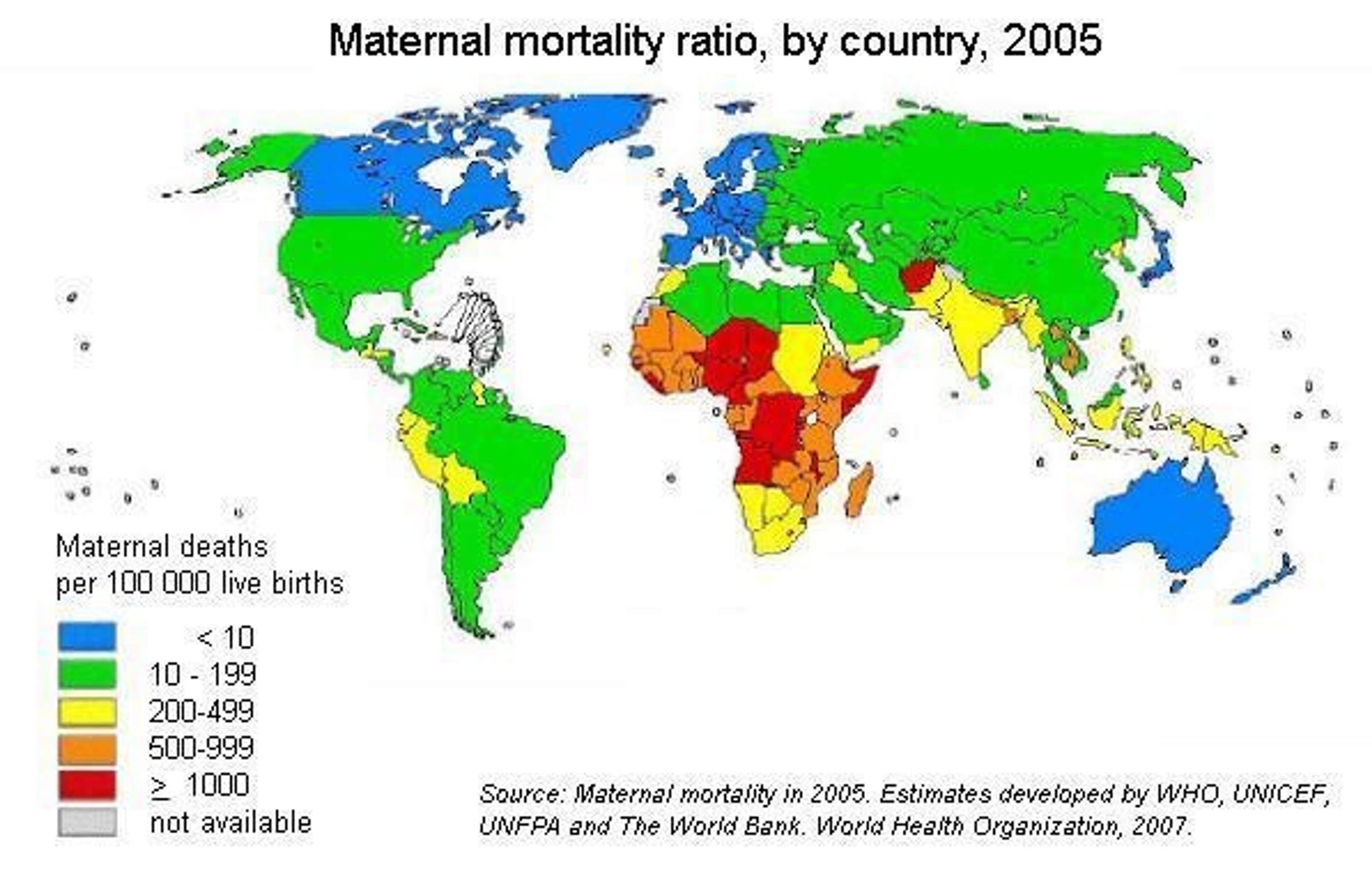

Maternal mortality refers to the death of women directly due to pregnancy or childbirth. The overwhelming majority of such deaths occur in developing countries and are mostly preventable with today’s technology. However, interventions in this area are often complex, as they require increased access to doctors, medical equipment, facilities and drugs, both during pregnancy and birth.

Globally, around 800 women die from preventable causes related to pregnancy and childbirth each day, and 99% of these deaths occur in the developing world. However, extensive efforts can reap results - between 1990 and 2010, maternal mortality dropped by 50% worldwide.[1]

COST-EFFECTIVENESS

A 2005 BMJ report states that interventions in both community and hospital care are highly cost effective - with the most effective interventions, such as community management of neonatal pneumonia, being in the 1–20 $/DALY range 2. However, current levels of access to such care are lower than required to meet the millennium development targets.[3]

The WHO advocates a three-fold strategy to combat maternal mortality:

- Reduce unwanted and high-risk pregnancies - This can be achieved by education and the provision of contraception. Such measures appear cost-effective (possibly in the 10–50 $/DALY range), mainly due to their low cost, and also help to reduce the prevalence of STDs and HIV. However, there is limited data available on the cost per DALY of using education and contraception to prevent maternal deaths.[4]

- Reduce the number of women who experience complications - Generally this requires better access to care before, during and after pregnancy. For example, STD/HIV prevention and management, tetanus toxoid immunisation, treatment of existing conditions such as malaria and hookworm, testing urine for bacteria, advice regarding nutrition, iron and folate supplementation, and hygienic conditions for birth. The cost-effectiveness of providing such care is estimated by the DCP2 to be $88 per DALY; that is 11.4 DALYs/$1000.[3]

- Reduce the number of deaths from complications - This entails better access to emergency obstetric care. Examples include provision of caesarean sections for cases of obstructed labour, giving oxytocin to prevent excess blood loss from haemorrhaging, and giving antibiotics to treat maternal sepsis. The DCP2 estimates that doctors’ services comprise the greatest cost of emergency obstetric care. The cost-effectiveness of the provision of maternal emergency care is $87 per DALY; that is 11.5 DALYs/$1000.[5]

Beyond the obvious benefit of DALYs saved for mothers, the other benefits of interventions in this area include the fact that reducing pregnancy-related deaths ensures that more children grow up with their mother’s care. This improves their health (girls, in particular, are more likely to survive if their mother is alive), and their education (children are less likely to be forced to stay and look after the home, or go out and work). These factors indirectly improve the cost-effectiveness of maternal mortality interventions.

Furthermore, interventions that reduce maternal deaths also reduce disabilities. This is not necessarily accounted for in the statistics or quantifiable in terms of DALYs (e.g. the DCP analysis does not include this). Finally, some of the worst consequences of maternal mortality may be social rather than physical: for example, women suffering from obstetric fistula (caused by obstructed labour) are frequently ostracised by their communities.

Conclusion

The cost-effectiveness of interventions aiming to prevent maternal deaths is reduced by the large and unpredictable number of potential complications, by the manpower needed to monitor pregnant women to diagnose problems earlier, and by the high levels of training and equipment needed to deal with severe complications. Many of the most effective interventions require significantly improved access to clinical health facilities and systems before they can be deployed; as such they are more complicated and vulnerable to failure compared with other health interventions such as bed nets or deworming. Nonetheless, maternal care interventions appear reasonably cost-effective and have numerous positive side-effects.

We will be investigating charities that reduce maternal mortality using demonstrated cost-effective methods, and we will compare their effectiveness with that of our currently recommended health interventions.

Sources:

- WHO: World Health Fact Sheet 2012.

- However, community management of neonatal pneumonia, which was most effective, is already at 95% coverage, so there is not a great deal of room for additional funding.

- Cost effectiveness analysis of strategies for maternal and neonatal health in developing countries. Taghreed Adam, Stephen S Lim, Sumi Mehta, Zulfiqar A Bhutta, Helga Fogstad, Matthews Mathai, Jelka Zupan and Gary L Darmstadt BMJ 2005.

- Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries. 2nd edition. Jamison DT, Breman JG, Measham AR, et al., editors. Washington (DC): World Bank; 2006, ch57.

- Jamison DT, Breman JG, Measham AR, et al: Ch 2, Ch 26

Last updated: in or before 2012