Take a second to think of the things you've spent your money on this past year, ranked from most to least important. Let's refer to this as a 'priority list'. What are some things that come to mind?

You probably started with the obvious things, like food, water, shelter, warm clothes, and a bed to sleep in. That's a good start, but keep going. Now you might be thinking of the money you spent to buy gifts for your family members on their birthdays, or perhaps the money you invested in your education. Of course, you wouldn't last long without food and water, so those were likely meaningful purchases. Similarly, you love and care about your family, so buying them nice things is likely important to you, as well. Keep asking yourself how important each purchase was to you as you make your way down the list.

As you approach the end of the list, however, you might notice something intuitive happens: because each subsequent item is less important to you, you will eventually reach a point where you probably wouldn't be that much worse off if you hadn't acquired the remaining items on the list. For example, those boredom-fueled quarantine purchases you made here and there this past April may not mean much to you now. It's okay though, I'm also guilty of making mindless quarantine purchases.

Neoclassical microeconomic theory agrees with your intuition. Consumer choice theory claims, among many other things, that we make decisions that aim to maximize our total satisfaction (or 'utility' in econ-speak) by spending each additional dollar on things that bring us the greatest satisfaction, and that buying the same thing repeatedly gives us lower satisfaction with each subsequent purchase. These two ideas make practical sense: you probably spend most of your money on things that are important to you. But while the first mattress you buy gives you a comfortable place to spend a third of your life, the seventh mattress begins to annoy your roommates as it clutters up the hallways.

The idea of becoming increasingly less satisfied with each additional mattress can be extended to the list as a whole. As you go down the list, the amount of utility you get for each purchase (or the 'marginal utility' of each additional dollar spent) likely goes down as well, as each subsequent item is increasingly less important to you --- if this wasn't true, you would've purchased the item near the top of the list!

For those of us who are financially well off (do keep in mind that earning over $58,000 USD per year puts one in the top 1% globally), the ends of our lists make increasingly little sense. This is even more apparent when we consider the fact that nearly 700 million people live on less than $700 USD a year, an amount you may have spent on at least one thing that wasn't very meaningful in the grand scheme of things.

If a Rolex doesn't make sense, what does? Consider giving to effective charities instead. These charities are often significantly better than ones that are merely good or adequate --- sometimes as much as 100 or even 1,000 times more effective. For most of us, the artisanal craftsmanship of a $10,000 watch couldn't bring greater utility than the personal satisfaction gained from providing 3 years of protection from malaria to 10,000 people --- keep in mind that number is half the seating capacity of Madison Square Garden --- via donating to the Against Malaria Foundation.

The economics behind donating

Even in a purely self-interested sense, giving can be one of the best uses of our money. Effective philanthropy offers serious bang for our buck. I do not make this claim spuriously, as there is evidence to support this idea.

According to the theory of pure altruism, donors do not care where a charity receives a given amount of money from personally, so long as the charity receives the amount of funding the donor wants it to receive. So, if the government taxes someone and hands those funds over to charity, the individual will reduce what they usually would have donated by an equal amount, resulting in a gain of zero for the charity. The implication from this is that there is no personal utility to be gained from altruistic acts --- all we care about is the outcome that the charity creates, regardless of who funds it.

The theory of perfect altruism does not always hold in practice, however. A study by James Andreoni, an economist who researches altruism, found that the "crowding-out" effect was not observed to be as substantial as the theory claims. This suggests that individuals do indeed derive some personal utility from the act of donating, sometimes referred to as a "warm glow". Interestingly, MRI scans show that donating causes the brain's reward centres to activate, according to a study from the University of Oregon.

The important conclusion from this is that there is a self-interested component of charity, one that I argue we should aim to pursue with a non-trivial portion of our spending money.

The warm glow feeling is fundamentally different from the utility we get from spending our money on consumable goods or experiences. You can be confident that each additional dollar you donate is being used to change someone's life for the better, especially if you donate to evidence-based charities with ample room for funding. As well, the stark wealth differences between developing and developed countries mean your money can likely bring much greater happiness to the recipients than an equal amount of money would have brought you.

Can money buy happiness?

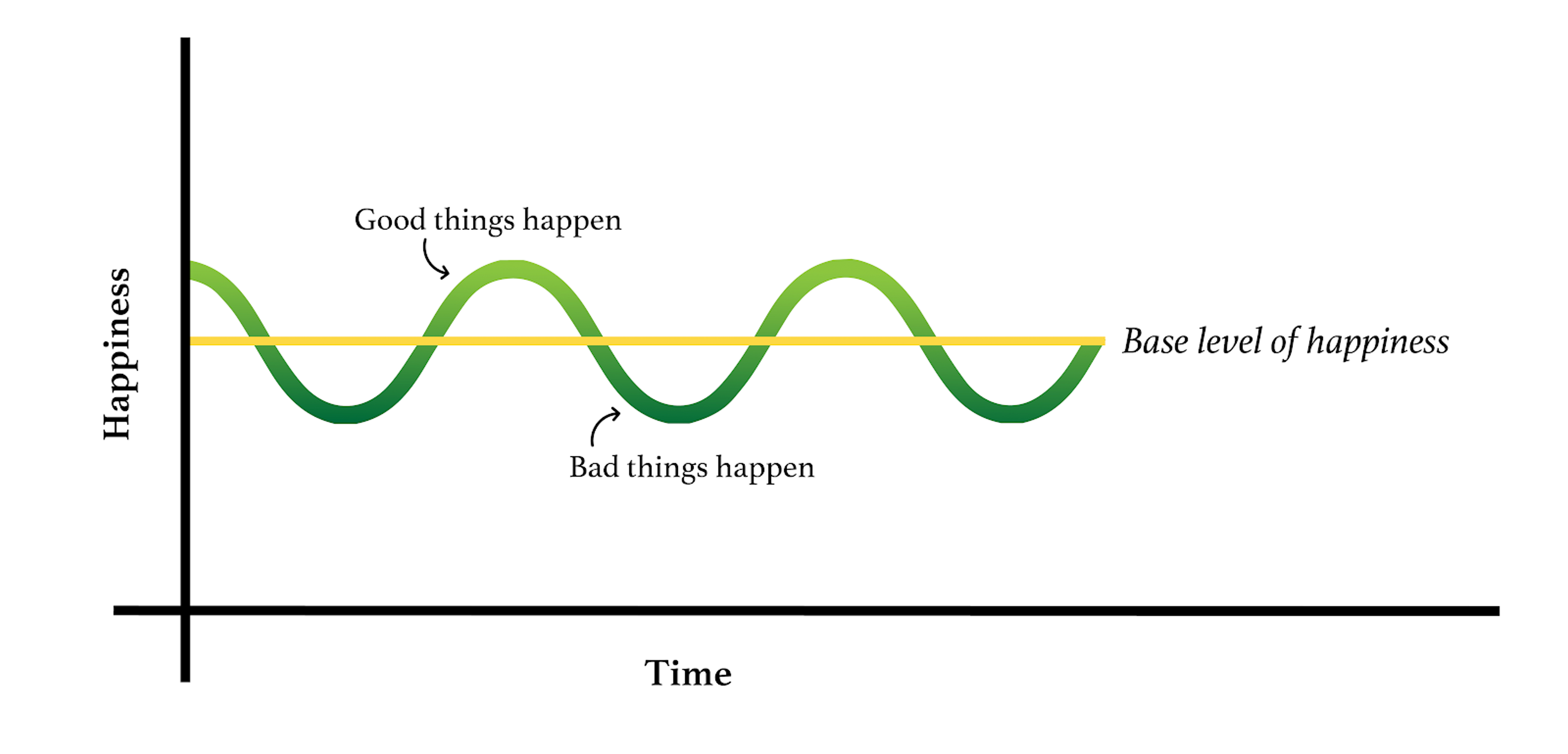

Yes, money can buy happiness, and it can buy far more if we spend some of it on others instead of ourselves. To explain, I'll introduce the concept of the hedonic treadmill, which describes how we return to relatively stable levels of happiness in light of major positive or negative events. Money clearly plays an important role in our wellbeing to a degree --- it's hard to be happy without a bed to sleep in or food to eat. Yet as our wealth rises, so do our expectations and desires, resulting in a hamster wheel-like situation in which we pursue a higher social status or endless material goods in perpetuity. Altruism can help us step off this wheel to the benefit of ourselves and others.

A question still lingers, however: At what point should we step off the wheel? To study the relationship between wealth and happiness, Daniel Kahneman and Angus Deaton, both Nobel laureate economists from Princeton University, found that the effects of income on emotional well-being peak at an income level of roughly $75,000 USD. The pair ultimately conclude that "high income buys life satisfaction but not happiness." to which I would like to add some additional nuance. Money alone doesn't make us happy, especially after we attain a comfortable level of income. But we can generate that coveted warm feeling of purpose by donating to highly effective charities, and there isn't a limit on how much warmth we can feel.

Nor should we forget the real purpose of donating: helping others. Effective donations can lift others out of poverty and allow them to move closer to the basic standard of living that we in high-income countries take for granted. Donations can generate more total happiness in the world than most of the things we in high-income countries buy ourselves.

"I guess basically one wants to feel that one's life has amounted to more than just consuming products and generating garbage. I think that one likes to look back and say that one's done the best one can to make this a better place for others. You can look at it from this point of view: what greater motivation can there be than doing whatever one possibly can to reduce pain and suffering?" - Henry Spira

Conclusion

At risk of allowing the hamster wheel metaphor to overstay its welcome, I will conclude by introducing a more appealing alternative: a wheel that generates happiness via altruism. A study by researchers from the University of British Columbia and Harvard University found that the well-established correlation between happiness and giving may in fact be causal. In other words, it appears that giving causes us to feel happy, not just that happy people tend to donate more. The researchers wrote that "Happier people give more and giving makes people happier, such that happiness and giving may operate in a positive feedback loop (with happier people giving more, getting happier, and giving even more)."

My purpose in writing this was not to make moral prescriptions to you if you don’t donate a significant portion of your income to effective charities. I recognize that this is a deeply personal decision that requires moral considerations that only you can weigh. But I do hope you will ask whether there is a chance that the feeling you would get from profoundly changing the lives of strangers in need would dwarf the pleasure you would get from buying more things for yourself that aren't guaranteed to make you happy.

A few months ago, I asked myself this question. I chose to take the Giving What We Can pledge, and this choice has made me feel happier and more fulfilled than ever before in my life. I believe that the vast majority of people --- especially you who made it this far into the article --- are generous, altruistic, and eager to sacrifice for others. I encourage you to try giving to an effective charity to see how good it can make you feel. In the words of Peter Singer from his book The Life You Can Save:

"I recommend that instead of worrying about how much you would have to do in order to live a fully ethical life, you do something that is significantly more than you have been doing so far. Then see how that feels. You may find it more rewarding than you imagined possible."

Further reading

If you liked this article, you might also want to check out:

- Giving and Happiness

- Can money buy happiness? A review of the new data

- How Rich Am I?

- You Can Make A Difference

- Why take a giving pledge when you could just donate?

- Related videos, books, podcasts and articles

Note on Killingsworth 2021 data

Since writing this article a new paper by Matthew A. Killingsworth was published in PNAS which expands on this research on income and happiness.

Here is an excellent Twitter thread from Michael Plant that covers the key insights from it.

In a nutshell, this study takes advantage of some interesting methodological tools to improve upon Kahneman & Deaton's study from 2010. The author used a smartphone app to periodically ask a large sample of people how they felt throughout the day with a continuous scale (as opposed to a binary yes/no), whereas the previous study asked people to recall how they felt in the past (do keep in mind that our memory can be finicky).

While the headline claims that happiness and life satisfaction increase past $75,000 (and indeed this is shown in the data), there are a few important things to note.

First, the increases in happiness from increased income are quite negligible: doubling one's income is associated with only a 0.1 standard deviation increase in happiness (read: a very small increase).

Second, money has a much larger effect on one's happiness only if one thinks that money is important. For those that don't, the same effect was not seen. Lastly, and perhaps most importantly, earning additional money was found to be less important the richer an individual was (so the increase in happiness from increasing one's earnings from $35,000 to $70,000 is roughly the same as going from $250,000 to $500,000). The author notes that "When interpreting these results, it bears repeating that well-being rose approximately linearly with log(income), not raw income. This means that two households earning $20,000 and $60,000, respectively, would be expected to exhibit the same difference in well-being as two households earning $60,000 and $180,000, respectively."

Overall, this study advances the state of the happiness-income literature, but doesn't necessarily arrive at a drastically different conclusion than its predecessor(s). Those of us who live in high-income countries can still create a whole lot more happiness with our income for others in low-income countries than we can for ourselves (hence why finding effective opportunities to do so is so important).