Comparing charities: How big is the difference?

It’s tempting to think that it doesn’t really matter where you donate as long as you donate somewhere. After all, aren’t most charities doing some sort of good? And with so many problems in the world, does it really matter which ones you choose to focus on as long as you help in some way? This is a fairly common point of view. But it misses something incredibly important:

Where you choose to donate can lead to huge differences in impact.

How big are these differences? There’s no exact answer to this question — it depends on factors like where you’ve previously donated and what type of impact you value. That said...

Our research team believes that many of us can easily 100x our impact by giving to charities that achieve more per dollar spent.

This really, really matters.

Variations in impact can be so enormous that your choice of where to donate can quite literally save lives.

In this resource, we'll begin with a couple charity comparisons, take a conceptual look at why differences in the impact of charities exist, and then discuss five ways you can increase the power of your donations.

A couple comparisons to get us started

For more information about each of these examples, and how we arrived at the figures, read the full case study.

Donation A

$15 to Toys for Tots, which provides toys to children in need.

Donation B

$15 to Evidence Action’s Safe Water Program, which delivers water treatment solutions to at-risk communities.

Difference in outcome

1 toy delivered to one child in need vs. clean water for a year for ten children.

Donation A

$3200 to the Navy SEAL Foundation’s education branch, which provides scholarships to recipients.

Donation B

$3200 to GiveDirectly, which provides cash transfers to those in extreme poverty.

Difference in outcome

Increase income for a scholarship recipient by $7500 vs. double the income of three people currently living in extreme poverty.

Note: As discussed in the case study, you can take the above comparison even further, since GiveWell's top charities are estimated to be at least twice as cost-effective as direct cash transfers. For example, for a bit more (~$5000 instead of $3200) you could — using GiveWell's "average cost" estimate — save a child's life.

Donation A

$1500 to the Battersea Dogs and Cats Home, one of the UK's oldest and best known animal shelters.

Donation B

$1500 to a corporate cage-free campaign program, such as The Humane League.

Difference in outcome

Pay half the cost for one dog/cat to be sheltered vs. reduce the suffering (through cage-free commitments) of around 15,000 egg-laying chickens.

Surprised at how big these differences are? You’re not alone. In 2023, a small study found that donors vastly underestimate how much charities vary in impact. And indeed, this seems consistent with the available data on donor behaviour1, along with some of the most cost-effective interventions in public health being severely underfunded.

So it might be useful to begin by taking a quick conceptual look at why these differences exist. We’ll then discuss five ways we think many donors can increase their impact (often by 100x or more).

Why are there such stark differences in the impact of donations?

It’s widely understood that products vary in their quality, efficacy, and how well they meet our specific needs. The most profitable businesses are many times more profitable than a “typical” business, a bestselling author far outsells an average author, and some products are incredibly expensive while others provide the same value for much less. But when it comes to charities, people are reluctant to acknowledge that there are large differences; after all, aren’t all charities doing good work?

We think it’s (usually) true that most charities have good intentions. But this doesn’t mean charity isn't subject to the same types of variation as in other areas. Organisations differ in what they do, how much it costs them to do it, and how far your dollar goes when you support them.

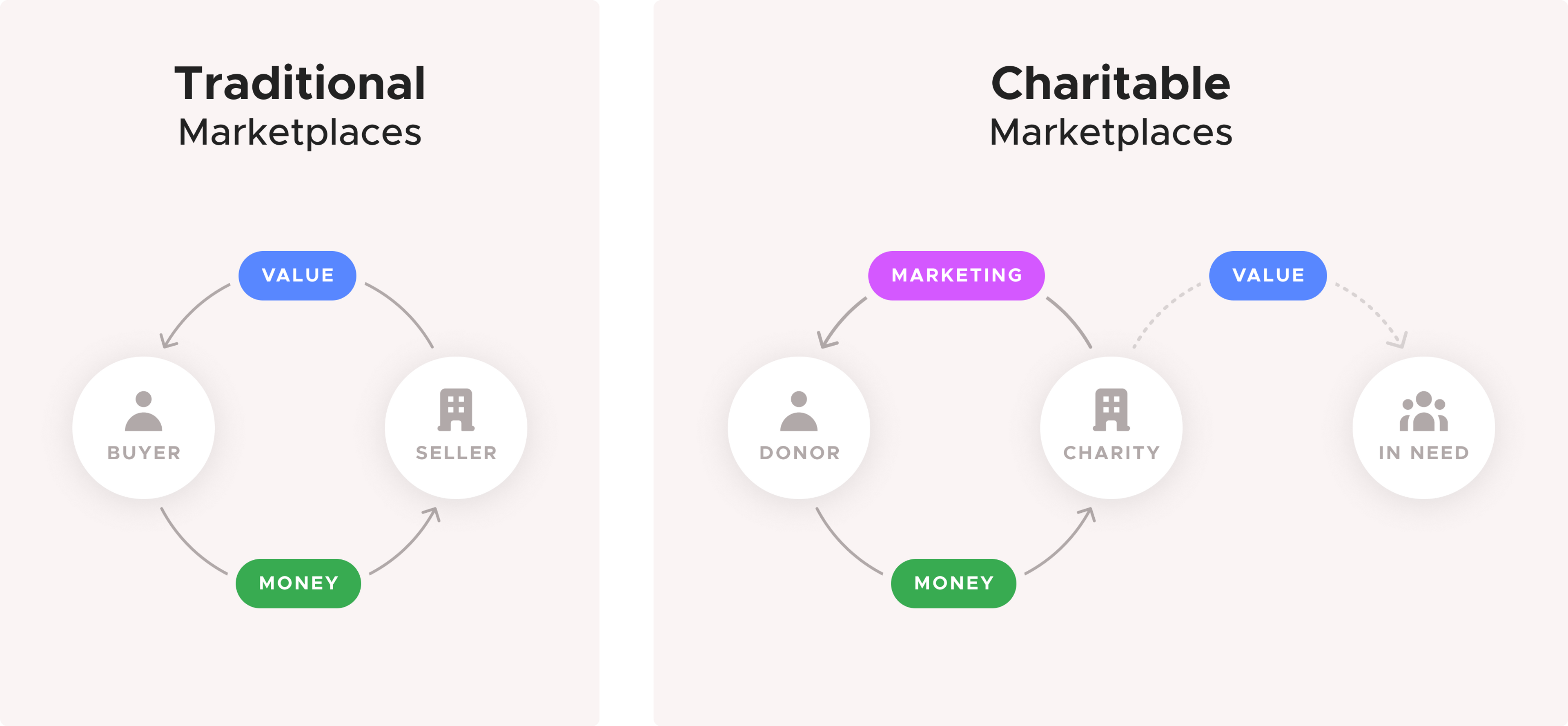

There's also an important difference between charity and business that make variations among charities even starker (and harder to navigate!): donors don’t directly experience what their donation does. Unless they are looking at outside impact evaluations, a donor’s only information about a charity’s impact is the charity’s marketing.

So while companies go bankrupt if they don’t deliver good products, charities can continue to exist even if they don’t make much of an impact, as long as they are good at marketing and fundraising for their programs. This means we should expect the charitable “marketplace” for donors to be much less efficient than the for-profit marketplace for consumers, and for there to be bigger differences between the impact of charities than between the quality of products.

Yet many of us behave as though it were the opposite. We sift through reviews, compare costs, consult experts, and “shop around” before making an important personal purchase, but tend to give intuitively when trying to improve the world. To take just one example, one study found that only ⅓ of donors do any research before donating and only 3% donate based on performance.

The takeaway? If we consider helping others to be more important than a personal buying decision, we might want to give it at least as much (and maybe more) careful thinking. Because while charity can do an extraordinary amount of good, the quality and efficacy of programs will vary tremendously.

So how can we be confident we’re directing our money intelligently?

We’ll cover five ways in the next section.

Five ways you can multiply your impact

We said at the start that we think many of us can 100x our impact by donating more effectively. Below, we’ve laid out five key principles to help you do that.

We see most of these five rules of thumb as a plausible way you could 10x your impact (depending on your starting point). Thus, you could in some cases 100x your impact even by following just two of them (10x10). (We say "in some cases" because a) there is some overlap in these principles — for example, impact-focused evaluators tend to support programs that are also highly cost-effective — so counting each principle as a separate 10x impact boost would include some double counting. b) donors may not reach a full 10x impact boost in all cases, even without considering overlap, depending on the specific rule of thumb and also the donor's starting point. In other words, following all five probably won’t 105 your impact but it will almost certainly give you an incredibly large impact boost!)

#1. Choose programs supported by an independent, impact-focused evaluation

What is an impact-focused evaluation?

It’s a deep dive into what a charity’s programs are accomplishing and how well (and how cost-effectively) that translates to impact. (Some charity evaluations focus less on impact and more on metrics like overhead, which we think doesn’t capture the full story.)

Why are impact-focused evaluations important?

Some charities sound great on paper, and you may intuitively think that there’s “nothing to prove”; their mission says it all. But even the best-sounding programs sometimes don’t work as expected, and there are big differences even among those that do work as intended. So one way to maximise impact is to make sure the programs you’re supporting have been evaluated by an independent, impact-focused charity evaluator (such as GiveWell). (You can read more about impact-focused evaluators here.)

Imagine hearing about an organisation — PlayPumps International — dedicated to bringing clean water to people in need. And not only is this organisation doing something important, it has a unique approach: making water pumps that double as merry-go-rounds. Children simply have to play on the merry-go-round, and this provides clean water for communities — eliminating the hard work of pumping water manually while simultaneously providing entertainment for the children!

If you think this sounds great, you’re in good company. PlayPumps rose in prominence very quickly, winning a World Bank Development Marketplace Award, receiving millions of dollars in American aid money, and getting attention from several celebrities including Laura Bush and Jay Z. It wasn’t until 1800 PlayPumps had been installed that some major issues came to light.

It turned out that children did not actually enjoy playing on the pumps; they required constant force to work and many injured themselves or became sick from the spinning. One organisation estimated that children would have to “play” for 27 hours each day to meet PlayPumps stated goal of providing water for 10 million people via 4,000 pumps. Furthermore, each pump costs about $14,000 to install (considerably more expensive than the hand pumps they replaced). Because children did not find the playpumps as entertaining as anticipated, the hard work of pushing the pump often fell once again to the village women, who tended to prefer the old manual hand pumps; they were easier to push and provided five times more water per hour than the PlayPumps.

The case of PlayPumps shows (painfully) that intuitions and good intentions are not enough. Millions were poured into the initiative before its issues came to light. But there’s a greater cost here: with so many suffering, the stakes are high. When we spend money on one thing, we can’t spend it on another.

In the case of delivering clean water, for the cost of just one playpump, a program like Evidence Action’s Safe Water Now (for which the evidence base extends well beyond intuitions) could have provided clean water to over 9,000 people for an entire year.

The case study above shows why — if you care about impact — you may want to look for programs that have been independently evaluated. After all, how many other organisations like PlayPumps might be operating with the best of intentions but the worst of impact? It’s pretty easy to see how we could have a sizable difference in impact by switching from supporting programs that sound great to those that have been independently shown to be exceptional.

#2 Help where you can help the most

Because of vast income differences between countries, your money goes a lot further overseas. While many people prefer to give locally, interrogating that impulse a bit might lead you to some surprising discoveries.

How can we estimate your difference in impact in those cases? Using the US as an example, we can compare the $40 US poverty line to the $2.15 global poverty line and deduce that Americans living in poverty are likely at least 10x richer than those living in poverty in lower middle income countries. And this has already been adjusted for differences in the cost of living in those countries. This means it would take about 10x more money to double the income of an American living at the poverty line than it would to double the income of someone living at the global poverty line.

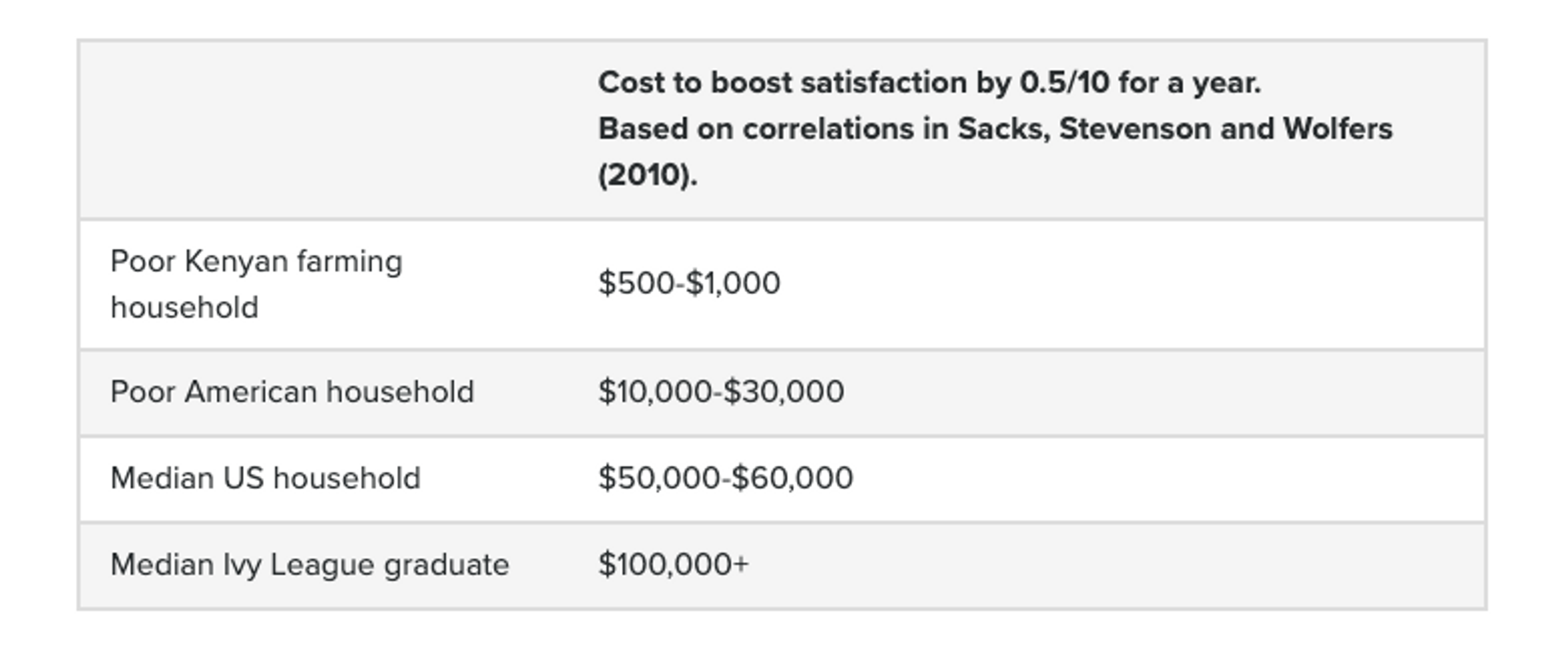

We can understand the significance of this by turning to a key principle in economics: there are diminishing returns to marginal consumption. A bit more simply put: money matters less when you have more of it. It's an intuitive idea: if you're earning $100,000 per year, another $1,000 per year is nice, but it's not going to make a big difference to your circumstances. If you're only earning $1,000 a year, an extra $1,000 will make a huge difference to how you are able to live.

For this reason, we think it’s more helpful to look at relative income gains rather than absolute income gains: plausibly, doubling your income when you live on $5 a day is as (or even more) meaningful as doubling your income when you live on $500 a day.

From: "Everything you need to know about whether money makes you happy" by Robert Wiblin. (Published by 80,000 Hours in March, 2016).

This implies that choosing charities (like GiveDirectly) that increase income for those living in extreme poverty over those working to alleviate poverty in higher-income countries could plausibly 10x your impact. You may be able to achieve something similarly meaningful — for example, doubling someone's income — but spend 10x less to do so.

A very different example of applying this principle: while 99.6% of the animals killed in the US are farmed animals — often living in terrible conditions — most of the donations to animal welfare focused organisations (about 66%) go to animal shelters, and just .8% go to farmed animal organisations.2 Yet donating to corporate campaign work is considerably more cost-effective: for every one dog or cat you could rescue from a shelter, you could likely improve the lives of many more farmed animals.

From: https://animalcharityevaluators.org/donation-advice/why-farmed-animals/

This isn’t to say that you shouldn’t help people in poverty in high-income countries or rescue dogs and cats — but spending some of your money where it can help the most is one way to significantly increase your impact.

#3 Find the most cost-effective programs working on a problem

Most people don’t systematically search through all charities working on a problem and try to select the best one. But, as mentioned above, there are impact-focused evaluators who do! One example is the charity evaluator GiveWell, who actually uses GiveDirectly (referenced above as a way to 10x your impact) as a benchmark, and only recommends charities that it believes are at least twice as cost-effectiveness as GiveDirectly style cash transfers. This means — taking GiveWell’s analysis at face value — that donating to a GiveWell top charity could be at least 20x more impactful than donating to a charity working to alleviate poverty in the US.3

#4 Look for leverage points

Directing your own resources towards high-impact causes and cost-effective programs is great, but you can potentially have an even bigger impact by looking for ways to influence a larger resource bank. This involves going one step away from direct intervention (for example, buying malaria nets) and supporting tractable ways to leverage more resources (for example, getting governments to reliably and equitably fund net programs). Of course, not everything has a tractable path towards leverage — malaria is likely an example where it makes more sense, at this moment, to continue donating to organisations like AMF, which do direct net distribution. However, when leverage is possible, the multiplier effects can be significant.

Many of the programs our donation platform supports use leverage points. For example, the organisation LEEP (Lead Exposure Elimination Project) leverages government resources in its effort to eliminate childhood lead exposure by helping governments implement lead paint regulation. Deworming programs such as those run by Evidence Action, Unlimit Health, and The END Fund leverage government, NGO, and investor resources to deliver Neglected Tropical Disease treatments to at-risk communities. And The Humane League, through its corporate campaign program, leverages the resources of corporations — redirecting them through commitments to buy only cage-free products. Giving multipliers — organisations that do outreach and education about effective giving in order to drive more money to particularly high-impact causes — are another example. Their work helps to fundraise for highly effective charities, leveraging the money people already plan to donate by helping donors spend it more effectively: current evidence suggests $1 spent on some such organisations can plausibly cause $10 dollars or more to be spent on high-impact charities directly working to solve some of the world’s most pressing problems.

#5 Expand your circle of concern

Most of us don’t sit down to systematically consider what our values are, and whether our actions are reflecting them. However, this is where you may be able to find the biggest gain. For example, if you begin to question the boundaries you might unconsciously be setting for yourself, you might find that you care about the suffering of many more beings than you thought you did.

For example, upon reflection, maybe you realise that although you’d been previously focused on helping only the people close to you, you care about those suffering far away too. (See for example, the “drowning child/shallow pond” thought experiment, which has led many to conclude that the suffering of others still matters even when we can’t physically see it.)

Or perhaps you realise that while you’d been previously focused only on helping people, you care about the wellbeing of other sentient beings too — and if you can prevent (with a relatively small donation) a large number of chickens from suffering in cages, you want to do that.

Or maybe you start thinking about all the people who will live on after you: Just like realising your desire to help people isn’t bounded by physical proximity, perhaps it’s also not bounded by time — after all, why is someone living 1, 10, 100, or even 1000 years from now less worth helping — if you can — than someone living now?

Including animals and/or future generations in your circle of concern will likely lead you to support work that is larger in scale (affecting more lives overall) and — by many worldviews — this can greatly increase your impact.

Concluding thoughts

We hope this list of tips was useful to you. For more guidance on how to donate effectively, check out our giving guides, browse this year’s charity recommendations, and/or get effective giving news and updates by subscribing to our newsletter.

What does the data comparing the cost-effectiveness of different interventions in an area tell us about differences between charities? What doesn't it tell us? We didn’t want to overwhelm you by including a data deep dive on this page, but if you’re interested, please see our discussion of the DCP-2 data (an often-cited resource comparing the effectiveness of global health interventions) and our key takeaways from this and other similar data sets.

Case Studies

Toys for Tots vs. Evidence Action (Safe Water Program)

The financial statements for Toys for Tots indicate that in the fiscal year ending December 2022, the organisation spent a total of $359,941,848 on toy distribution to children in need.

This covered the distributions of “24.4 million toys, books, and games to 9.9 million children in need.”

Dividing the total spent by the number of toys (359,951,848 /24400000 = 14.751715082), we can see that about $15 provides one toy (or book/game) to a child in need in the US

Providing toys to children who might not otherwise get them for the holidays is great — and $15, at first glance, seems like a fair price to pay to increase a child’s happiness. But now consider that globally, 2 billion people lack access to safe drinking water, this causes roughly a million preventable deaths every single year, and many of these deaths are children under 5. If you could spend $15, the price of one toy, and instead use it to provide clean water to a child for a year, would you?

Evidence Action estimates that its Safe Water Now program provides clean water to people in need for just $1.50 per person per year.4 This means that for $15, you could provide not just one child, but ten children access to clean water for a year, which is a fairly significant difference in impact compared with providing one toy.

Increasing income: Navy SEAL vs. GiveDirectly

The case study above focused on two vastly different outcomes. Let’s now compare similar outcomes. Focusing on the outcome of increasing income, which is known to affect wellbeing, we can begin by looking at a charity that has not only a four-star Charity Navigator rating, but a perfect score of 100, and which claims on its website to “rank higher than 99.9% of charities nationwide.” Additionally, it has a “highly cost-effective” designation from Charity Navigator.

This is the Navy SEAL Foundation, which Charity Navigator states in the Impact & Determination section of its Impact & Results metric “increases income for a scholarship recipient by 7500” for “roughly $3200.” This means that donating 3200 would roughly increase the income of one scholarship recipient by 7500. Indeed, this seems like a pretty good return on investment — you are putting in 3200 and getting out more than double the amount.

However, let’s compare the Navy SEAL Foundation to another charity that increases income — GiveDirectly. GiveDirectly provides direct cash transfers to those living in extreme poverty globally. Taking into account operational/delivery costs, 90 cents of every dollar goes directly to its recipients, who are (at least in its international programs) typically people living on less than $800 per year, adjusted for purchasing power. ($2.15 p.p.p.d global poverty line). This means that for just $1000 (which would be the equivalent of giving $900 to someone living in extreme poverty) you could more than double someone’s yearly income.

To compare this outcome to Navy SEAL’s, let’s be sure we are using equivalent donation amounts. Since we know $3200 increases one person’s income by $7,500, we’ll use the same donation amount for GiveDirectly, which — based on the calculations above — would mean we could double the income of three people living in extreme poverty and still have a couple hundred bucks left over1.

We can take this comparison even further by extending the outcomes beyond income.

The charity evaluator GiveWell “searches for the charities that save or improve lives the most per dollar.” As discussed above, GiveWell has found such exceptional giving opportunities that it only recommends charities it believes are at least twice as cost-effective as GiveDirectly-type cash transfers. One of these charities is Helen Keller International’s Vitamin A supplementation program, which GiveWell estimates (as of Feb. 2024) could save a life for between ~$1,000 and ~$8,500 (depending on the country). This means that —instead of increasing the income of a scholarship recipient by 7500, that $3200 donation could instead be used — in some countries — to save a child's life.

Battersea Dogs & Cats Home vs Cage-free Corporate Campaign Programs

Let's now look at an example in a different high-impact cause area. The Battersea Dogs and Cats Home, one of the UK's oldest and best-known animal shelters, reports that it costs around £46000 every day to care for their animals. To get the yearly cost, we can multiply 46000x365, which works out to 16,790,000 GBP. Let's convert that to USD for consistency with our other estimates — in 2024, that works out to around 21 million USD.

Next, to get the cost of caring for one animal, we need to know how many animals Battersea cares for per year: according to their website, that's around 7,000 cats and dogs. Thus, if we divide 21 million by 7000, we should get the cost of caring for one animal for one year, which is $3000 USD. (Of course, keep in mind this is a rough, BOTEC calculation — it's not clear how many of the 7,000 animals cared for during the year are in care at any time, meaning some of the animals likely get rehomed before a full year is up. However, we can likely assume that the average cost of caring for one animal in a given year is around $3000 USD.)

A $1500 donation to the Battersea Dogs and Cats Home, then, could only cover half of what it costs (on average) for Battersea to care for one animal within a given year.

In contrast, based on an estimate by Rethink Priorities, we can work out that for each dollar donated to highly effective corporate campaign work (such as the type engaged in by The Humane League) the living conditions of 9–120 egg-laying hens are significantly improved. Let's take the lowest end of that range given the estimate is a few years old and early campaigns were particularly cost-effective. If we assume that $1 reduces suffering for about 10 chickens living on factory farms, then for $1500, you could remove one of the worst forms of suffering (battery cages) for 15,000 chickens during the entire course of their approximately one-year life.

That's a pretty significant difference, especially when you consider the degree of suffering battery cages can inflict as compared to the degree of suffering of a cat/dog living on the street. (Of course, we also must weigh the fact that even with cage-free commitments, the chicken may undergo other forms of suffering, and likely continue to be confined to life on a factory farm.) Even still, the comparison here is striking — removing one of the worst forms of suffering for 15,000 chickens vs. paying for half the care of one cat or dog in a given year.

Stay in touch

Join our monthly newsletter to get the latest effective giving news. No spam—just news.

Support us directly

Our site is free to use but not free to operate.

Help us keep GWWC up and running.