Road Traffic Injuries

Giving What We Can no longer conducts our own research into charities and cause areas. Instead, we're relying on the work of organisations including J-PAL, GiveWell, and the Open Philanthropy Project, which are in a better position to provide more comprehensive research coverage.

These research reports represent our thinking as of late 2016, and much of the information will be relevant for making decisions about how to donate as effectively as possible. However we are not updating them and the information may therefore be out of date.

Cause Area: Road Traffic Injuries

Most of us have seen the aftermath of numerous road accidents and many of us will have been in one ourselves, but we are likely to underestimate the sheer scale of the devastation caused by road traffic injuries (RTIs). In 2010, according to the Global Burden of Disease Study, RTIs killed around 1.33 million people worldwide1 – more than 3,000 a day – making them the eighth biggest killer in the world, ahead of diseases like tuberculosis.2

| Disorder | Mean rank (95% UI) |

|---|---|

| 1. Ischaemic heart disease | 1.1 (1 to 2) |

| 2. Lower respiratory infections | 1.9 (1 to 3) |

| 3. Stroke | 3.1 (3 to 4) |

| 4. Diarrhoea | 4.8 (4 to 7) |

| 5. Malaria | 5.5 (3 to 8) |

| 6. HIV/AIDS | 5.6 (4 to 7) |

| 7. Preterm birth complications | 6.3 (4 to 8) |

| 8. Road injury | 7.9 (5 to 9) |

| 9. COPD | 9.8 (9 to 12) |

| 10. Neonatal encephalopathy | 10.8 (9 to 14) |

| 11. Tuberculosis | 11.2 (9 to 14) |

| 12. Neonatal sepsis | 11.3 (7 to 17) |

Table 1: Global years of life lost ranks with 95% Uncertainty Intervals for the top 25 causes in 20101

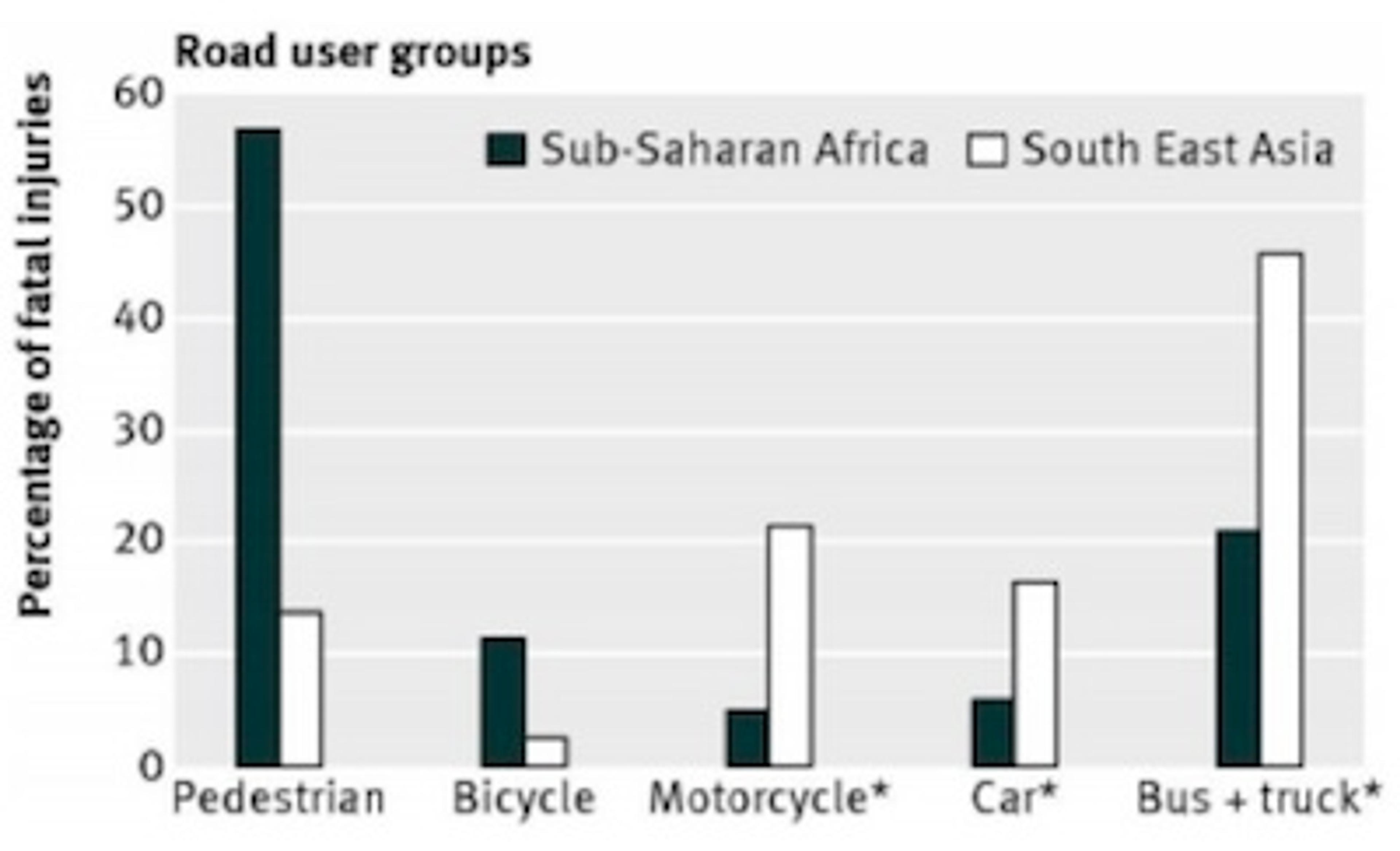

This annual death toll is greater than the number of people killed in the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan over the last decade. In addition, between 20 and 50 million people are estimated to be disabled or injured each year.3 Middle income countries are hardest hit, with 80% of road traffic deaths but only 52% of the world’s registered vehicles.4 Perhaps surprisingly, half of all road deaths are among pedestrians, cyclists and motorcyclists.4

Looking to the future, as low and middle income countries develop and more people are able to afford motorised transport, the number of road deaths is likely to increase. The WHO projects that road deaths will overtake HIV/AIDS and diarrheal disease as a cause of death by 2030.2

Figure 1: Attribution of fatal road traffic injuries by road user group in sub-Saharan Africa and in South East Asia 5

The annual global economic costs of RTIs are estimated at $518bn, though the WHO says this figure may be a considerable underestimate.3 Moreover, in many countries road safety efforts go underfunded.

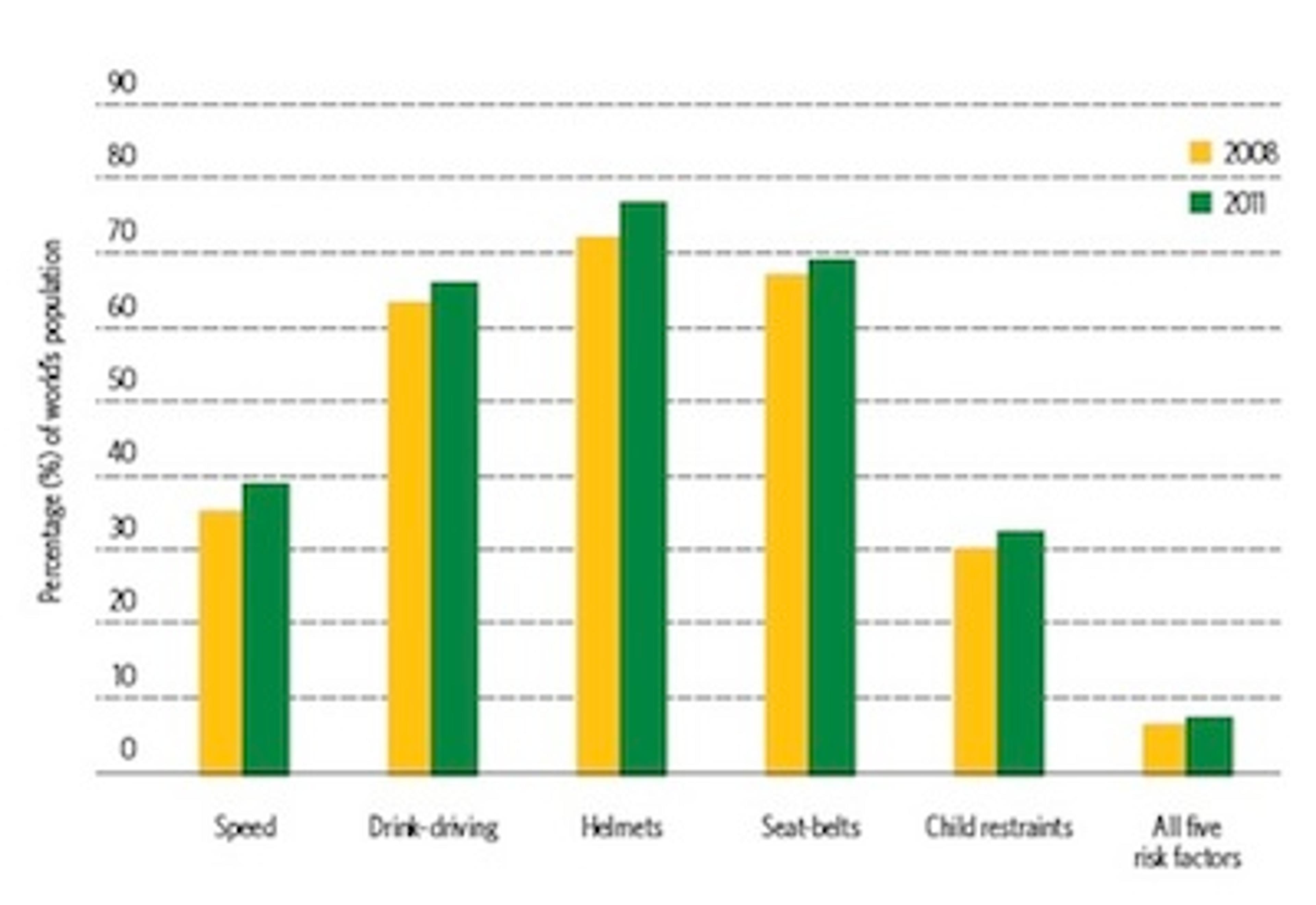

As a consequence of the startling problem of RTIs, the UN General Assembly proclaimed a Decade of Action for Road Safety (2011-2020).6 However, today less than 10% of the world population has comprehensive legislation on all five key risk factors for road safety: speed, drink-driving, helmets, seat belts and child restraints.4

Figure 2: Increase in the percentage of world population covered by comprehensive legislation on five key road safety risk factors 2008-20114

There appears to be, then, significant room for improvement at the policy level.

Cost-effective interventions?

Publications such as Disease Control Priorities 2 (DCP2), World Health Organisation (WHO) CHOICE and The Copenhagen Consensus try to provide information for policymakers on which interventions produce the most human benefit for our buck. These estimates can guide us towards general areas in which there is potential for high levels of charity cost-effectiveness.

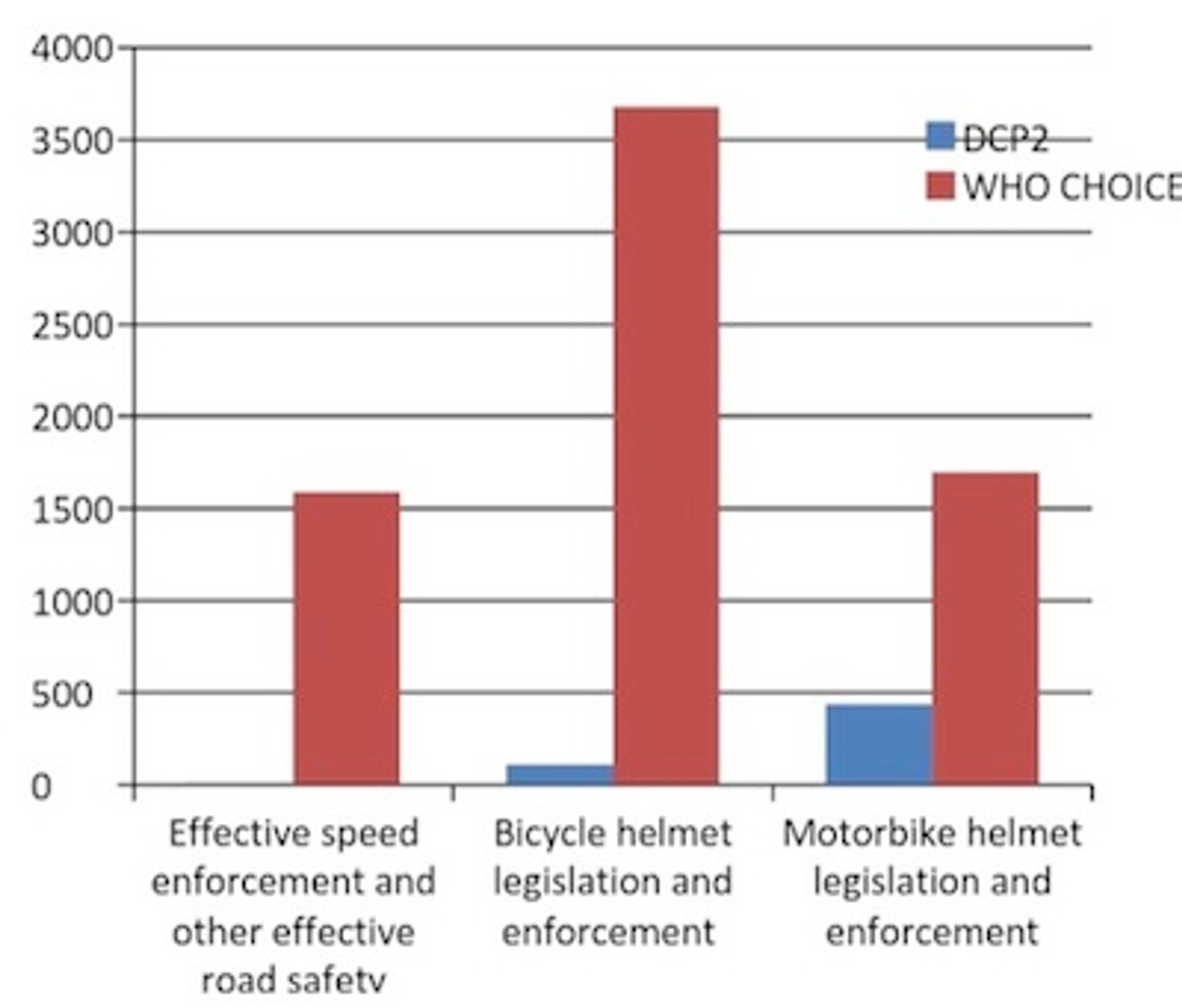

DCP2 and WHO CHOICE give very different estimates of the cost-effectiveness of road safety interventions implemented by governments. Professor Adnan Hyder, Director of The International Injury Research Unit, John Hopkins (IIRU-JH), who was involved in both the DCP2 chapter and the WHO CHOICE paper, told us that this is chiefly because they answered different questions. For WHO CHOICE the question was: what must be spent per DALY averted if there is no good legislation and no social momentum? In contrast, DCP2 asked: what must be spent per DALY averted if there is already good legislation and a supportive social environment? The results are as follows.57

| Intervention | As measured by DCP2 | As measured by WHO CHOICE |

|---|---|---|

| Enforcement of speed limits and other effective road safety regulations | $10/DALY | $1,500/DALY |

| Bicycle helmet legislation and enforcement | $107/DALY | $3,678/DALY (SE Asia); $1,233/DALY (Sub-Saharan Africa) |

| Motorcycle helmets legislation and enforcement | $437/DALY | $1,696 (SE Asia); $6,683 (Sub-Saharan Africa) |

The chart below summarises the difference:

The following three interventions are assessed by only one source:

- Speed bumps - DCP2: $5

- Drink driving legislation and enforcement - WHO CHOICE: $2236 in Sub-Saharan Africa and $2731 in South East Asia.

- Seat belt legislation and enforcement - WHO CHOICE: $4579 in Sub-Saharan Africa and for $2502 in South East Asia.

Which estimate is most helpful for our purposes?

If the DCP2 figures can be matched by any charities, that would make them serious contenders to be amongst our recommended charities. If the WHO CHOICE estimates are more applicable, then road safety charities are much less effective than our recommended charities.

Which estimate should guide us? There are a number of factors to consider. Firstly, it is not immediately clear which of the questions by DCP2 and WHO CHOICE is more relevant for our purposes here. On the one hand, governments rather than road safety charities would bear most of the costs of sustaining the interventions over time but, on the other, some of the areas in which the most promising road safety charities operate – South East Asia and Africa – to a large extent lack a supportive regulative and social framework.

We suspect that the cost-effectiveness of road safety charities will be somewhere between the DCP2 and WHO CHOICE estimates. A cost-effectiveness projection of a programme recently implemented by the road safety charity Bloomberg Philanthropies may be instructive. The study projects that the intervention would save a year of life for around $300, which is around a fifth as cost-effective as our recommended charities.8

All of this said, the most important thing to note here is that the existing data appears to be very limited. Esperato et al note that the available academic articles on cost-effectiveness exhibit four main weaknesses:

These are (1) not focusing on a specific intervention, (2) not having specific baseline data, (3) not having a control group (i.e. counterfactual), and (4) not adjusting for potential confounders.8

For example, only two of the effectiveness studies they found accounted for the counterfactual by having a control, and only one study accounted for potential confounders. Given that Esperato et al engaged in such a wide-ranging literature view, this should make us have serious doubts about the robustness of any existing cost-effectiveness estimates of road safety interventions in the developing world. WHO CHOICE and DCP2 also seem to be working with very limited developing world data.

In sum, we do not yet have reason to completely rule out road safety charities, but we should be suspicious about claims that they could rival our currently recommended charities. Unless a road safety charity presents strong evidence showing the high cost-effectiveness of their activities, we ought not to recommend them.

Assessing Road Safety Charities

There are relatively few road safety charities and of the major ones than exist, many of them are quite young. We looked at a range of traffic charities and have concluded that though none should be recommended now, three may be worth assessing again in a few years’ time.

The International Road Assessment Program (iRap)

iRap engages in a range of activities, including inspecting high-risk roads and developing star ratings, safer roads investment plans and risk maps. They also track road safety performance so that funding agencies can assess the benefits of their investments.

iRap has numerous cost-effectiveness analyses of prospective road infrastructure projects across the world. They suggest that some government projects can avert a death or serious injury for less than $200. However, these are cost-effectiveness assessments of government projects, not of donating to iRap itself. So far as we know, they have yet to perform a cost-effectiveness assessment of their own work and they did not respond to our queries about their own cost-effectiveness. Nonetheless, there work appears to potentially have a large impact. It would be worth enquiring again in a one or two years to see if they have performed any cost-effectiveness analyses of their own work.

Asia Injury Prevention (AIP) Foundation

The AIP Foundation is an Asian NGO which has a five pillar approach to road safety: programmes targeted at vulnerable road users; public awareness education; legislative advocacy; helmet production; and research monitoring and evaluation of their efforts.

Source: AIP Foundation - Helmet Safety

AIP Foundation has various impressive achievements so far. In 2007, they combined legislative advocacy and public awareness education to successfully push for mandatory motorbike helmet laws in Vietnam. This has undoubtedly saved many lives. Nellie Moore, their Junior Monitoring & Evaluation Manager, told us that, by their own estimates, as a result of the programme, $2.6bn was saved, 412,200 road injuries were avoided and 20,600 fatalities were prevented in Vietnam. If this is accurate, then AIP Foundation is potentially very cost-effective. It spent nearly $2.5m in 2013. If we assume it spent $2m every ten years with the sole consequence of a mandatory helmet law in Vietnam which saved 20,600 lives, then their activities would have saved a life for $970. This is around half the cost offered by our recommended charities.

However, there are a number of caveats. Firstly, they have yet to do a rigorous cost-effectiveness study of their own work. Ms Moore told me they are carrying two out at present, which should both be ready by next year. Secondly, it is not clear whether the helmet legislation would have happened anyway without the efforts of AIP Foundation. Thirdly, Vietnam might have been a particularly good opportunity for motorbike helmet intervention, which could not be matched in other countries.

There is, then, reason to be cautious around claims about the cost-effectiveness of AIP Foundation, but nevertheless to be optimistic about the good it does. We recommend returning to this charity in one or two years to look at the outcomes of its cost-effectiveness assessments.

Amend

Amend operates in Africa and according to the WHO “the interventions promoted by Amend are perfectly in line” with those being promoted by the WHO.

Amend’s Director Jeffrey Witte provided helpful information when asked about cost-effectiveness. Overall, the message was that at the moment we simply do not know enough to reach a verdict about the cost-effectiveness of interventions in the developing world. He said that there are very few or zero papers which prove to a standard publishable in a peer-reviewed journal that any intervention has reduced RTIs in Africa (or anywhere else in the developing world). However, in January, Amend is to embark on a two year project funded by the FIA Foundation to perform a rigorous evaluation of the impact of their infrastructure programme on injury rates.

Amend’s scientific focus is certainly to be commended and it would be worth looking again at them in a few years’ time.

The Bottom Line

RTIs are a huge and growing problem across the world. However, what data there is at the moment suggests that it is unlikely that any road safety charity could rival our currently recommended charities. Moreover, there is very limited data on the cost-effectiveness of road safety interventions in the developing world. Some charities operating in the area are promising and we ought to return to assess them again in a few years’ time. For now however, we cannot recommend any road safety charities.

Further Reading

[Road Traffic Injuries: Assessing The Global Burden And Charities Working In The Area], Giving What We Can's comprehensive report into Road Traffic Injuries