Development, Population Growth and the Mortality-Fertility Link

Many people express the concern that population growth is a barrier to development . Different mechanisms have been postulated as to how population growth could impede development. For instance, when parents have large families they may be less able to invest in their children, whether this be by providing them adequate nutrition, healthcare or schooling. [1] [2] [3]The effects of this lack of investment are thought to undermine development.

Sometimes these concerns are raised regarding charities that save lives through medical interventions, with some claiming that money would be better spent limiting population growth. What’s more, if limiting population growth is an objective for development, then saving lives might at first glance seem to run counter to this goal.

One popular response is to argue that saving lives does nothing to increase population growth and in fact actually decreases population growth . The Gates Foundation and Gap Minder have both claimed that reducing mortality causes the fertility of the population (the number of children per woman) to decrease. The long-term effect of this is will be to reduce population growth. [4][5]

There are biological reasons for supposing high levels of mortality will not constitute a barrier to population growth. The death of an infant will lead to a cessation of breastfeeding meaning that the mother is able to fall pregnant again sooner than if the child had survived. [6]Further, if a large family size is desired for cultural or economic reasons, parents may take into account high levels of mortality by having more children in order to ensure that they reach their desired family size. [7]

Reducing mortality may actually decrease population growth. We might think that parents choose to have large numbers of children because they rely on at least some of their children surviving to provide for them in old age and carry on the family lineage. If mortality is high then parents will choose to have more children to try to increase the odds that at least some of them reach adulthood. However, if mortality is lowered, parents will have more confidence that their children will reach adulthood. Therefore they will have less of an incentive to conceive more children. [8]

If the above arguments are sound, then we have a strong response to concerns about population growth. By saving lives we also reduce population growth. But is this always the case?

In this report I look at the link between mortality reduction and population growth. I find that we should not be confident that reducing mortality will always reduce population growth . Methods other than reducing mortality seem more effective in reducing population growth.

A Strong Correlation Between Mortality and Decreased Fertility

Since 1950 we have seen extremely strong correlations between reductions in mortality and reductions in fertility. [9] [10]A recent review states that:

“A ‘folk regression’ of the fertility trend on the mortality trend would conclude that saving one life prevents two births.” [11]

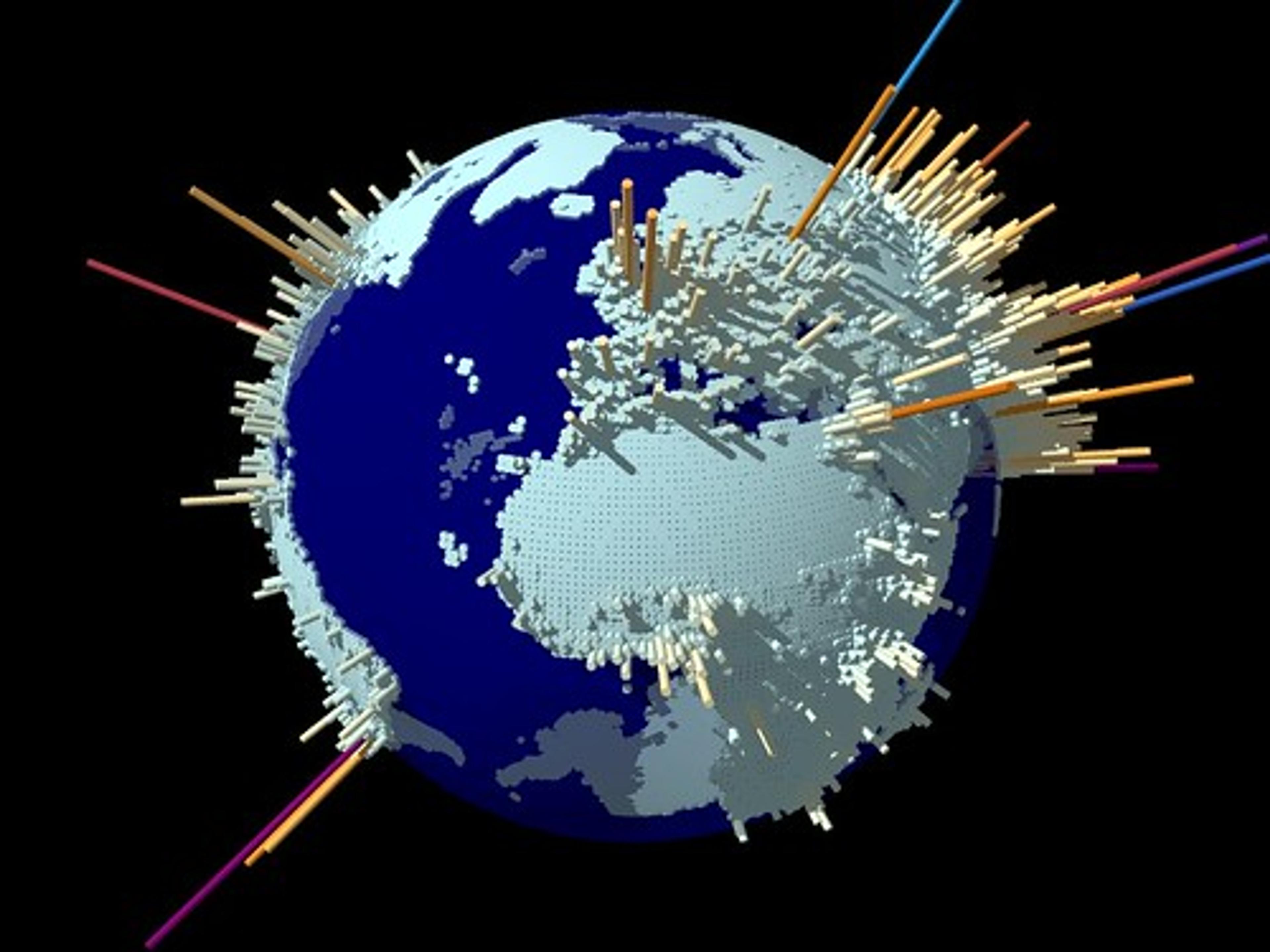

Furthermore no country has ever experienced a fall in fertility without first experiencing a fall in mortality . Contrary to popular belief, it does not look like we are heading towards an ever increasing population. Across most of the world, we have seen dramatic reductions in fertility accompanying drops in mortality. In Europe and North America the number of children per family has fallen to between 2 and 3 children, which keeps the population at its current size. In Latin America and Asia, we have also seen rapid convergence to lower fertility rates, with many countries that were once characterised by large families now near the fertility rates of the richest countries. [12]

If family size remained at around 2 children we would see dramatic population growth over the next few decades due to decreased mortality, but ultimately by 2100 the population size would stabilise. [13]

Taking a Closer Look

But correlation does not mean causation. The drop in mortality since 1950 took place alongside many other developments such as economic growth, increasing levels of education, female empowerment, and provision and acceptance of family planning services. Although we might expect all of these trends to lead to decreased fertility, identifying the relative effect of each of these factors is extremely difficult. [14]

For one, it is plausible that there are complex causal relationships between each of these factors. Maybe a combination of increased education and decreasing mortality is needed to see any significant impact on fertility. Also, the desire to limit family size might struggle to translate into drastically lower fertility without widely available modern methods of contraception.

That reductions in mortality are not always the best way to reduce population growth can be seen by comparing the fertility rates of different countries. Both Bangladesh and Niger have traditionally had large family sizes. Bangladesh has now reached a fertility rate of 2.4 children per women whereas Niger has a fertility rate of over 7 children per woman. It does not look like a high level of mortality is the main issue preventing Niger from reaching lower levels of fertility. In Bangladesh child mortality fell at a steady rate from 198.4 out of 1000 in 1980, to 143.7 out of 1000 in 1990. During this time total fertility dropped from 6.4 children per woman to 4.6 children per woman. Contrast this with recent developments in Niger: over a ten year period between 1998 and 2008, Niger experienced an even more dramatic fall in child mortality than was seen in Bangladesh, from 245.2 per 1000 to 141.4 per 1000, yet total fertility only fell from 7.8 to 7.6. [15]

To cite another example, Ethiopia and Uganda have similar levels of child mortality. In 2010, under 5 mortality was 75.6 per thousand in Ethiopia and 78.4 per thousand in Uganda. Both countries had seen large drops in child mortality since 1990 when under 5 mortality stood at 205 per thousand in Ethiopia and 178.7 in Uganda. Yet total fertility in Ethiopia presently stands at 4.8 children per woman as opposed to 6.2 children per woman in Uganda. It doesn’t look like it is high levels of mortality that are preventing Uganda from reaching Ethiopian levels of fertility. [16]

A recent review of the literature relating mortality to decreased fertility and population growth by David Roodman came to the following conclusion:

I think the best interpretation of the available evidence is that the impact of life-saving interventions on fertility and population growth varies by context, above all with total fertility, and is rarely greater than 1:1 [rarely enough for the fertility decline to exceed the mortality decline in terms of effect on population size]. In places where lifetime births/woman has converging to 2 or lower, family size is largely a conscious choice, made with an ideal family size in mind, and achieved in part by access to modern contraception. In those contexts, saving one child’s life should lead parents to avert a birth they would otherwise have. The impact of mortality drops on fertility will be nearly 1:1, so population growth will hardly change.

In light of these findings it seems we should be wary of supposing that further decreases in mortality in high fertility countries will lead to decreased population growth . Indeed, as the above extract claims, in some contexts decreasing mortality may be increasing population growth as the impact of declining fertility on population growth may be less than the contribution of more people living long enough to start families of their own. The above review claims that in certain countries, such as Niger and Mali, for every six children that do not die in infancy, only 3 or 2 fewer children will be born. Here, saving lives can be expected to increase population in the short-term. [18]

Nonetheless, it is important to remember that the causal pathways relating mortality to population growth are complex and difficult to assess. In some contexts high levels of mortality might well have been the chief barrier to decreasing fertility. Additionally, although the effect of mortality decreases on fertility might be weak in isolation, it might be that in some contexts decreasing mortality alongside other interventions may be necessary to reduce fertility and limit population growth. This belief is evidenced in another review of the literature:

“If a consensus emerges at all from the wealth of past studies on mortality and fertility declines, it would be that while a direct, independent effect of mortality change on fertility change is often found to be weak, ‘child survival and family planning programs play important complementary roles’.” [19]

It seems fair to say that we cannot assume that decreasing mortality is an effective means of reducing population growth. The impact of reduced mortality on population growth will depend on the specific context in which the reduction takes place .

Population Growth in Sub-Saharan Africa

Those who are concerned with the effects of population growth on development should predominantly be concerned about Sub-Saharan Africa. Whereas other regions of the world have converged on or are about to converge on average fertility rate of just over two children per family, fertility declines in Sub-Saharan Africa have lagged behind the rest of the world. [20]This lag in declining fertility rates is projected to lead to high levels of population growth in Sub-Saharan Africa. [21]

A particular extreme example is that of Niger, where the population has tripled since the 1970s and is expected to triple again before 2030. [22] Fertility declines have begun later and been slower in Sub-Saharan Africa than in other regions. [23]In part this might be due to the fact that declines in mortality took place later than in other regions. But it appears that there are other factors which are preventing a more rapid decline in fertility.

Some of these are regional-specific factors that lead to a desire for large families, including religious beliefs, marriage practices and communal land ownership. [24]However, many of these factors - such as low levels of female education and a lack of governmental enthusiasm for family planning - have been faced in other areas. [25]

The success of some African countries in dramatically lowering fertility has been attributed to the provision of family planning programmes. This is the case in Ethiopia [26], Kenya [27(which reached a fertility rate of 4.6 in 2010), and Rwanda [29], which has seen a particularly dramatic decline in fertility from 6.1 in 2005 to 4.6 in 2010.

We have good reason to suppose that decreasing child mortality in Sub-Saharan Africa will lead to decreases in fertility. But we also have good reason to think that in many instances falls in mortality may in fact lead to population growth in the short term, as the decrease in fertility may be outweighed by the increasing number of people who survive to have families of their own.

Comparing countries in Sub-Saharan Africa to one another as well as to countries from other regions indicates that factors other than the level of mortality are the major impediment to decreasing fertility and population growth. We have good reason to believe the conclusion of a recent UN report that suggests that the most effective means to achieve decreases in fertility and population growth in Sub-Saharan Africa would be to invest in family planning services and female education.

Mortality, Population Growth and Aid: Some Conclusions

Decreasing mortality may have an important role to play in moving to a low fertility society. Nevertheless, we cannot assume that reducing mortality in a particular instance will lead to decreases in fertility that are significant enough to outweigh the direct contribution to population growth caused by reduced mortality.

There is good reason to believe that the major barrier to decreasing fertility and population growth in Sub-Saharan Africa today is not high mortality but factors such as the low levels of female education and lack of family planning programmes . If reducing population growth is of overriding concern, it seems that the most effective means to do this would be to attempt to implement the above programmes rather than trying to further reduce mortality.

It is worth remembering that reducing population growth is but one concern amongst many when deciding which interventions to support in low income countries . Just how damaging population growth is for development is unclear and there is dispute as to whether it is particularly damaging at all. Even if population growth does significantly impede development, it is still plausible that donating to charities that directly save lives and reduce morbidity confers more valuable benefit than donating to charities that try to reduce population growth.

Finally and most importantly, the historical record shows us that we are able to massively reduce fertility and thus (in the long-term) population growth whilst also dramatically reducing mortality . Additionally, over the long-term it is plausible that these processes are mutually supporting. Concerns about population growth at worst may give reason to move marginal dollars from health interventions to interventions supporting other causes such as family planning, but they certainly do not give any reason to abandon the process of attempting to reduce mortality and morbidity in low income countries.

References

[1]Health and Economic Growth, Wile pp. 656-657 http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780444535405000033#

[2]When Does Improving Health Raise GDP?, Ashref et al p. 8

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3860117/

[3]Copenhagen Consensus 2012 Challenge Paper on Population Growth, Kohler p.50

[4]Gates Foundation Annual Letter 2014

http://www.gatesfoundation.org/Who-We-Are/Resources-and-Media/Annual-Letters-List/Annual-Letter-2014

[5]Will saving poor children lead to overpopulation?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BkSO9pOVpRM

[6]Mortality Decline and the Demographic Response: Toward a New Agenda, Montgomery pp 5-6.

http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.175.9555&rep=rep1&type=pdf

[7]Ibid

[8]Will saving poor children lead to overpopulation?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BkSO9pOVpRM

[9] http://blog.givewell.org/2008/08/03/infant-mortality-and-overpopulation/

[10]Macroeconomics and Health: Investing in Health for Economic Development, Sachs pp. 35-38.

[11] http://davidroodman.com/blog/2014/04/16/the-mortality-fertility-link/

[12]Ibid

[13]Don’t Panic

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FACK2knC08E

[14] http://davidroodman.com/blog/2014/04/16/the-mortality-fertility-link/

[15]Numbers taken from http://www.gapminder.org/data/

[16]Ibid

[17] http://davidroodman.com/blog/2014/04/16/the-mortality-fertility-link/

[18]Ibid

[19]Demographic pressure, economic development, and social engineering: An assessment of fertility declines in the second half of the twentieth century. Heuveline p.389.

[20]How Exceptional is the Pattern of Fertility Decline in Sub-Saharan Africa? Bongaarts pp. 1-4.

[21]Don’t Panic

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FACK2knC08E

[22] http://davidroodman.com/blog/2014/04/16/the-mortality-fertility-link/

[23]How Exceptional is the Pattern of Fertility Decline in Sub-Saharan Africa? Bongaarts pp. 1-4.

[24]Ibid pp. 1-2.

[25]Ibid.

[26]Ibid p.11

[27] http://www.gapminder.org/data/

[28]The Effects of Improved Survival on Fertility: A Reassessment, Cleland pp. 84-85

http://www.jstor.org/stable/3115250?loginSuccess=true&seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

[29]How Exceptional is the Pattern of Fertility Decline in Sub-Saharan Africa? Bongaarts p.11