Global priorities research

Global priorities research asks the question: if we were aiming to do as much good as possible, what should we prioritise?

This kind of research can involve:

- Identifying previously unknown cause areas.

- Deciding which cause areas deserve more attention.

- Resolving some of the difficult questions that arise given our limited resources.

To give some examples, global priorities research has helped to identify the importance of safeguarding the long-term future, and bolstered the case for devoting greater resources to biosecurity and beneficial artificial intelligence. One example of a "difficult question" that global priorities researchers work on is whether it is generally more effective to spend philanthropic resources now (or in the near future), or invest them to be spent at a later date.

Global priorities research asks questions about "how things should be" and "how things are":

- Questions that ask about "how things should be" require us to think through our values. For example, how much should we prioritise the welfare of animals? Research of this kind tends to fall in the domain of philosophy.

- Questions that ask about "how things are" require us to build an accurate view of how the world works. For example, does increasing economic growth reduce existential risk? Research of this kind tends to fall in the domain of economics.

Why is global priorities research important?

Global priorities research is important because its scale is potentially enormous, but it receives relatively little attention. Even though progress on global priorities research can be difficult to measure or predict, we think the expected benefit of devoting additional resources to this cause is very high.

What is the scale of global priorities research?

When thinking about the scale of a cause, we often look at how many people's lives it affects, and how significantly it affects them. But it's hard to measure the scale of global priorities research in this way, because its effects tend to be indirect: progress in global priorities research means identifying new problems, or determining which problems are more or less important, rather than solving the problems that directly affect individuals today. Therefore, it would be misleading to compare the number of people that could be affected by these two very different approaches (direct and indirect).

Another way to measure the scale of a cause is to think about how much room for improvement there is, and how good improvement would be. In the case of global priorities research, this means considering the question: "How much better would the world be if there were no need for further global priorities research?"

We can consider this question in two parts:

- The potential to identify new cause areas

- The value of adjusting our priorities over known causes

Historically, humanity's track record of identifying important cause areas does not look great. Many of the most important problems throughout history — including slavery and climate change — are things that most people, at most times, failed to recognise as problematic. More recently, we might add animal welfare and concern for future generations to this list. Therefore, there are likely to be important cause areas in the future that are unknown today, implying that the scale of global priorities research might be very large indeed — since it would include everyone impacted by the as-yet-unknown causes.

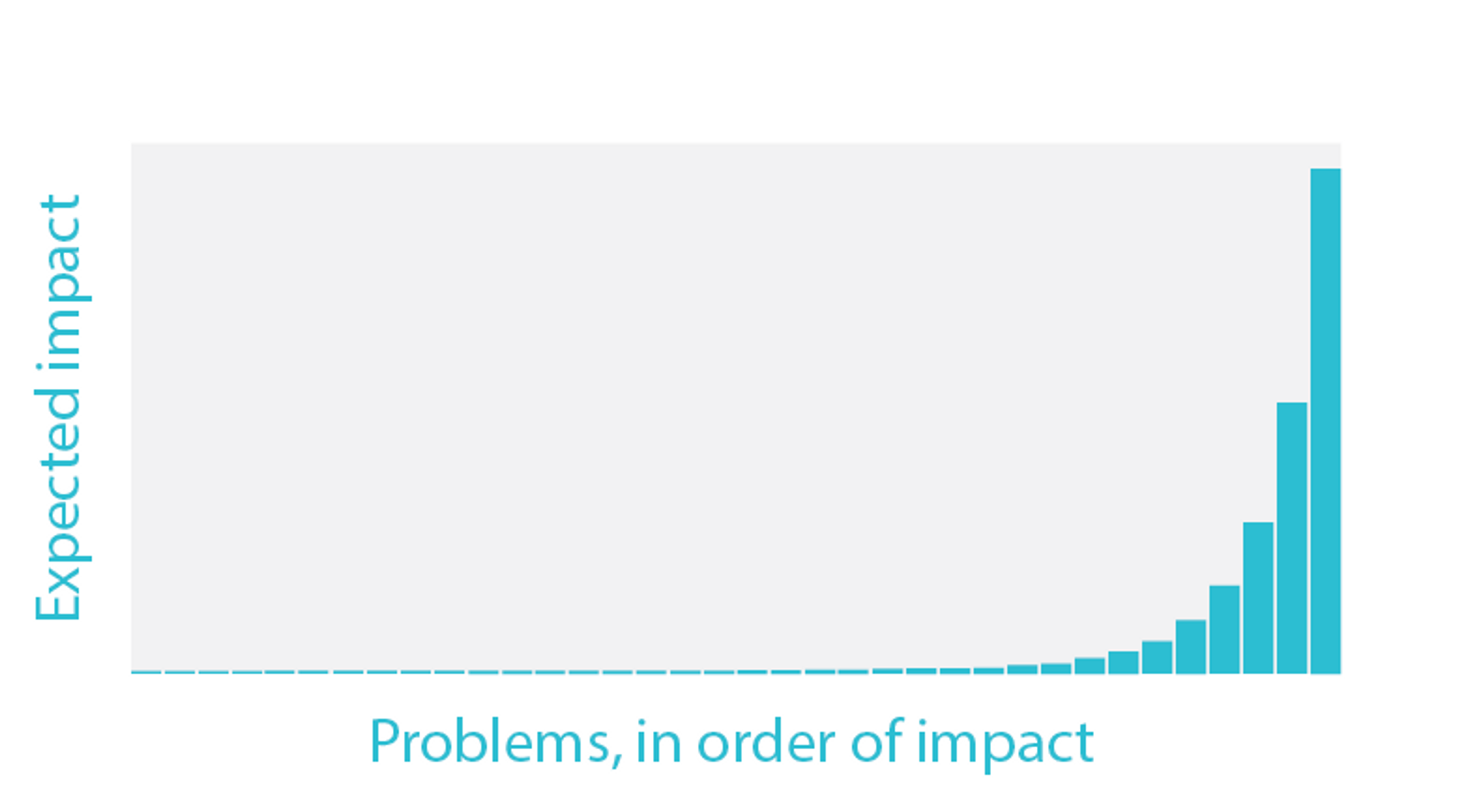

What about adjusting our priorities over known causes? We know that interventions can vary greatly in terms of their expected impact. For example, the cost effectiveness of a health intervention in a low-income country is typically many times greater than that of a similar intervention in a wealthy country. Also, estimates of this sort tend to be highly uncertain, suggesting that improvements to our estimates could lead to significant positive impact: we could avoid spending too much on causes we mistakenly think are high impact, and spend more on cause areas we mistakenly think are low impact. The graph below illustrates this — because of the big differences between problems, it is important that we recognise which problems fall on the right side of the graph.

Credit to 80,000 Hours.

This line of thinking seems particularly plausible when estimating the effectiveness of broad interventions like improving institutional decision-making or promoting peace, which focus on unforeseeable benefits and ripple effects. Broad interventions may be highly impactful, but their effects are especially difficult to estimate. In other words, it's particularly hard to place interventions like these on the graph above. By helping to improve our estimates, global priorities research could identify which broad interventions are unusually effective, and which are not.

Is global priorities research neglected?

There are only a handful of research centres around the world dedicated to global priorities. The number of people working directly on global priorities research is probably fewer than 300, while the total budget of all these centres is probably in the realm of $6–12 million USD per year. For comparison, an average secondary school in the UK supports around 1,000 students on a budget of around $6 million USD. These considerations suggest that global priorities research is highly neglected, especially when compared to its scale.

However, the boundaries of exactly what counts as global priorities research are a little fuzzy, and there is certainly research taking place outside of the main centres that could be counted. For instance, there are many people conducting research within specific cause areas whose work might be used to inform questions of prioritisation. As a result, the numbers above are probably an underestimate of the total resources being spent on global priorities research.

Is global priorities research tractable?

Global priorities research appears only moderately tractable. On the one hand, it is not a cause with known solutions, where all that is required is money to pay for them or people to implement them. On the other hand, it is an area with a fairly strong track record, which has consistently discovered decision-relevant results, and has already contributed to millions of philanthropic dollars being more effectively spent.1

There is also a lot of uncertainty around the tractability of global priorities research. Because global priorities research involves discovering new knowledge, we cannot say for sure that there are still highly valuable things to discover, nor can we rule it out. That said, there are certainly promising questions that remain unanswered, many of which can be found in the Global Priorities Institute research agenda. One example from this agenda is the question of whether or not we should extend political franchise to future generations — and if so, how this should be implemented.

Overall, we expect additional resources devoted to global priorities research to continue to make progress on questions of this sort, but it may be slow going, and the importance of the results may vary widely.

How can we make progress on global priorities research?

Doing the research

The main route to progress on global priorities research is to just do the research. In other words, we achieve progress by having researchers with relevant expertise apply their skills to the problems of the field. Many important and well-defined questions in global priorities research remain unanswered, and there is valuable work to be done addressing these.

Building the field

A complementary approach is to build the research community across multiple disciplines. Currently, the global priorities research community is relatively small, and draws primarily on the academic disciplines of economics and philosophy. But other disciplines could bring new techniques, insights, and perspectives. For example, the Legal Priorities Project addresses problems in global priorities research from a legal perspective. So there is field-building work to be done within these disciplines to establish global priorities research as a recognised sub-field where important and high-quality work occurs.

Why might you not prioritise global priorities research?

Results are not guaranteed

Unlike many other cause areas, donations to global priorities research are unlikely to lead directly to a certain number of lives being saved, or a specific reduction in extinction risk. Instead, work on global priorities research might yield only insignificant results for decades, or might quickly uncover considerations that radically alter the way we think about doing good. Supporting a cause area with such wide variation in outcomes is a matter of individual preference.

We might already be on the right track

Another reason to be sceptical of global priorities research is if you are optimistic about our current priorities. Maybe you think we mostly have things figured out, at least in terms of which cause areas are important. If so, this would mean that global priorities research is unlikely to discover new and important cause areas, or lead to significant adjustments in the way we prioritise important problems.

It is important to realise that this view aligns with our track record of changing global priorities over time. Though you probably agree that previous generations were badly mistaken about things like slavery and women's rights, you might think there are a finite number of moral breakthroughs to make. From this perspective, we would already have found the low-hanging fruit of global priorities research, with only a few small advancements remaining.

However, even if we have identified the main problems, there would still be a lot of valuable work to be done. There is a world of difference between correctly recognising that slavery, women's rights, or climate change is a problem, and building a rigorous — and persuasive — case to that effect.

Pure research is just not effective

A final reason to be wary of global priorities research comes from the idea that academia, or research more broadly, is generally not very effective. You might think that global priorities research loses importance because its results are unlikely to have practical impact — perhaps they will be politically unpopular, or are just likely to be ignored.

While there is some truth to this line of thinking — and our political leaders are often not as sensitive to new evidence from research as we might like — it is also true that research results do sometimes translate to real-world impact.

Many large government and industry organisations have already been receptive to results from global priorities research. For example, in September 2021, the UN Secretary-General released a report calling for a UN Declaration on Future Generations. This report was directly informed by advice from Toby Ord, a senior research fellow at the Future of Humanity Institute. In his address to the UN General Assembly, UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson quoted Ord in expressing the view that humanity is "just old enough to get ourselves into serious trouble." This shows that a finding from global priorities research — the idea that safeguarding the long-term future is extremely important — can lead directly to public statements of support from world leaders.

What charities, organisations, and funds work on global priorities research?

You can donate to several promising programs working in this area via our donation platform. For our charity and fund recommendations, see our best charities page.

How else can you help?

In general, discovering and adjusting our priorities is really hard. This is especially true when we are talking about things that many people care deeply about: it can be difficult to acknowledge that a given cause area might be more or less important than you had thought, or more or less important than another cause.

Perhaps one of the most useful things that individuals and organisations can do to further the work of global priorities research is to cultivate a mindset of adaptability. In doing so, we can help ensure that any results from global priorities research will be turned into real-world impact.

Learn more

- Global priorities research (80,000 Hours)

- An introduction to global priorities research (EA Student Summit)

- A research agenda for the Global Priorities Institute (Global Priorities Institute)

- Our common agenda (UN Secretary-General)

In addition, the following organisations offer a wealth of additional information on global priorities research:

Our research

This page was written by Toby Newberry. You can read our research notes to learn more about the work that went into this page.

Your feedback

Please help us improve our work — let us know what you thought of this page and suggest improvements using our content feedback form.