Economic Empowerment (Part 1 of 2)

Giving What We Can no longer conducts our own research into charities and cause areas. Instead, we're relying on the work of organisations including J-PAL, GiveWell, and the Open Philanthropy Project, which are in a better position to provide more comprehensive research coverage.

These research reports represent our thinking as of late 2016, and much of the information will be relevant for making decisions about how to donate as effectively as possible. However we are not updating them and the information may therefore be out of date.

Cause Area: Economic Empowerment

Poverty is a significant challenge to human well-being, and its eradication is a high-priority goal for development. This report focuses on the income-based definition of extreme poverty. There are a variety of interventions which attempt to alleviate poverty: we focus on microcredit and direct cash transfers since, for these interventions, we were able to find adequate evidence about organizations administering them.

Microcredit consists of the provision of small loans to people living in poverty. In the past, there has been limited evidence on its effectiveness and the evidence that did exist has been criticised for methodological deficiencies. A recent review, however, concluded that microcredit has had only limited success as a tool to escape poverty.

Direct cash transfers consist of direct disbursements to households. Conditional cash transfers (CCTs) make the disbursements conditional on the satisfaction of certain behavioural requirements, generally concerning the health and education of children resident in the household. Unconditional cash transfers (UCTs) do not make the transfer dependent on any conditions.

Cash transfers have been shown to increased consumption patterns among recipient households, with notable results in improved food consumption. Evidence also shows that transfers can increase investment, enabling long term improvement in earnings.

Conditional and unconditional cash transfers have different advantages. Evidence suggests that, at least in some circumstances, CCTs improve accumulation of human capital more effectively than UCTs. On the other side, UCTs unconditionally provide a safety nets for all poor households and allow vulnerable households to identify their own needs. Crucially, due to their ease of administration, disbursement, and the monitoring and evaluation of their effects, they are one of the most scalable interventions in development. The use of technology further decreases the administrative costs of unconditional cash transfers. A recent study comparing manual distribution of cash transfers with distribution via mobile technologies found that mobile delivery reduced both distribution costs for the implementing agency and collection costs for the recipients.

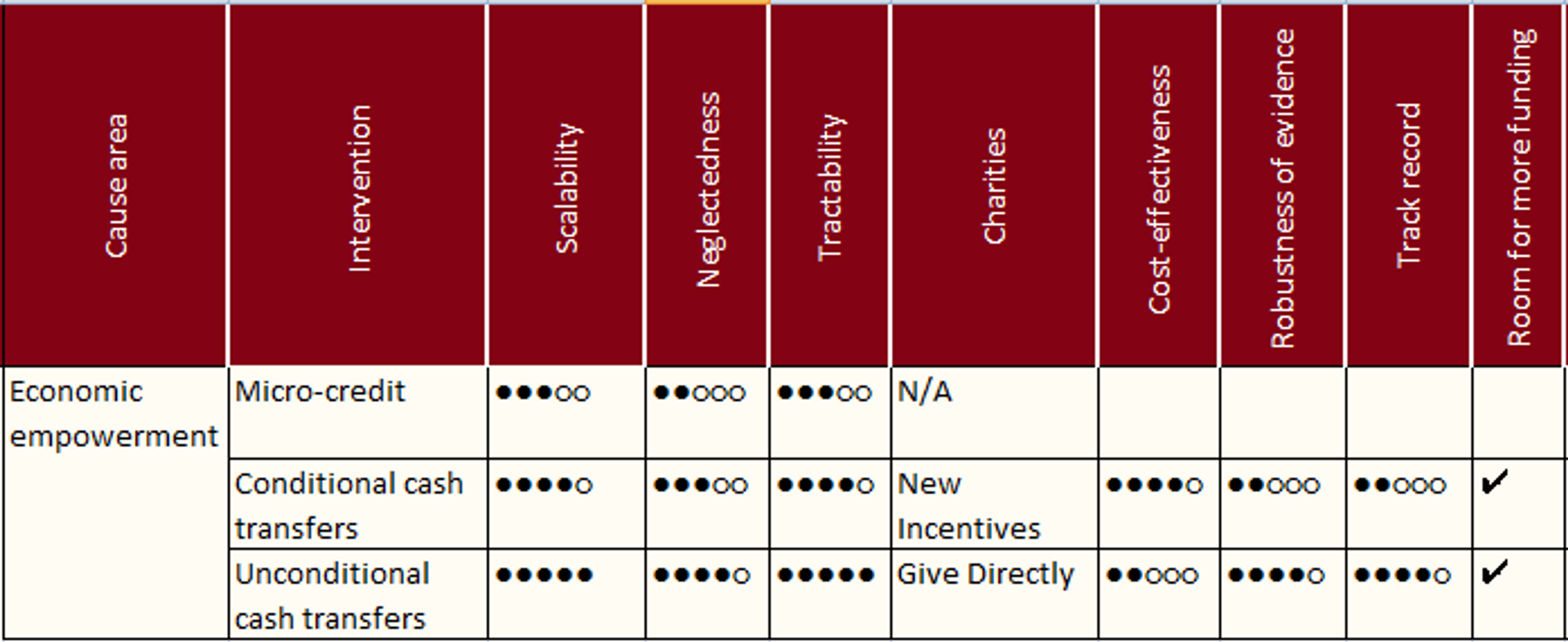

The table below summarises advantages and disadvantages for each of the interventions considered:

| Microfinance | Conditional Cash Transfers (CCT | Unconditional Cash Transfers (UCT) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Advantages | Self-sustainingAccess to credit | Increased consumptionAllows for savings and investmentAccumulation of human capital | Increased consumptionAllows for savings and investmentTargets the very poorestEasy to administer and scale |

| Disadvantages | Risks of harmDoes not target the poorestDifficult to take risksProfit objectives | Requires good enough supply of servicesRisks excluding the worst offHarder to measure and scale due to the conditions attached | Less accumulation of human capital than CCTs |

We conclude that the current evidence does not support microcredit as a high impact option for donors, although we would welcome further studies in this area. Donors who are looking to have a greater impact with their donations may be better off donating to charities which conduct direct cash transfers.

We have identified two effective charities working in this area. The first is New Incentives, which operates in the Akwa Ibom State in Nigeria. They offer conditional cash transfers to mothers who are HIV-positive or have at-risk pregnancies. They provide transfers conditional on the mother registering her pregnancy and being tested for HIV, delivering in a clinic, and (if HIV-positive) having their newborns tested for HIV. The second is GiveDirectly, which operates in Kenya and Uganda, making unconditional cash transfers to very low-income households. It uses an electronic payment system to transfer roughly $1,000 to each household, or around one year's budget for a typical household.

1.Cause level investigation

1.1 What is the problem and how badly does it affect people?

Poverty is a multidimensional concept, incorporating a number of different factors which impact the lives of the poor. This report however, will focus on the income-based definition of poverty. The World Bank estimates that 900 million people were living in extreme poverty (less than $1.90 PPP a day) in 20121. Poverty is a significant challenge to human well-being, and its eradication is a priority goal for development2. Lack of economic resources has direct consequences on food security3, access to healthcare4 and safe water services5. Moreover, living in poverty may generate a self-sustaining cycle keeping the poorest people from improving their living conditions, a so-called poverty-trap,6 though a recent study using 20 years of panel data in Northern Nigeria finds no clear evidence of poverty traps7.

1.2 What would it take to solve it?

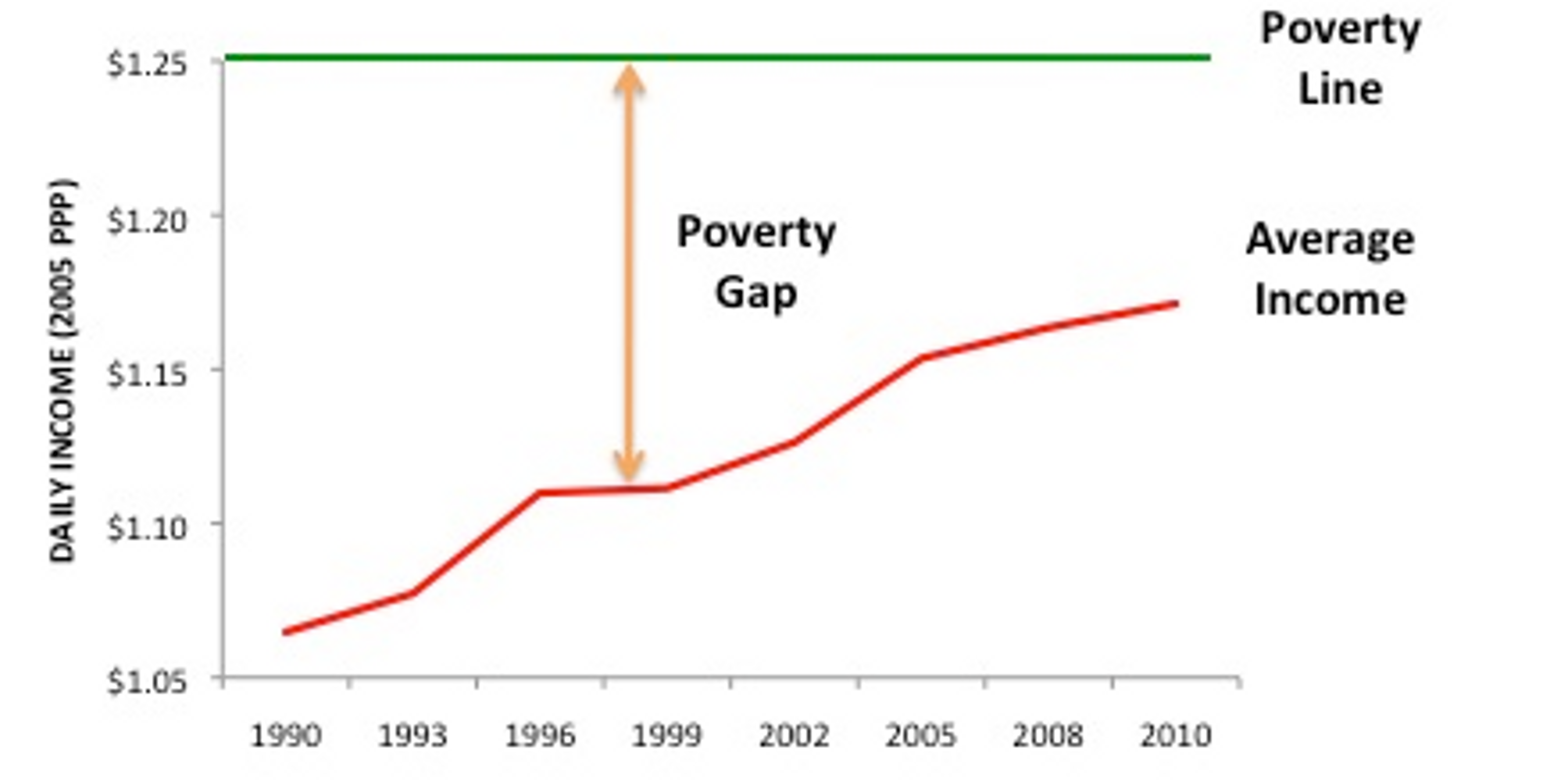

Extreme poverty is not inevitable. Poverty rates were cut in half between 1990 and 2010 mostly due to economic growth in China and India8. In 2011, 60 per cent of the world’s extreme poor lived in just five countries9. The average poverty gap, which represents the difference between the average income of those living in extreme poverty, and the poverty line, fell from over 25 cents to below 10 cents between 1990 and 201010 (see graph below). The aggregate poverty gap (the amount of money it would take to raise all incomes above the poverty line) has been estimated at $169 billion dollars (in 2005 PPP dollars)11. This is equivalent to every person in the OECD12 giving around $140 (although lump sum transfers on this scale may create distortionary incentive effects13.)

Figure 1: Poverty Gap over time. Source: World Bank14

1.3 How can you address the problem?

Poverty reduction policies are focused on three primary aims15:

- Social protection - alleviating the symptoms of poverty by ensuring a minimum level of consumption;

- Human capital accumulation - improving health and education for the next generation; and

- Sustainable exit from poverty - improving productivity and self-reliance of the current generation.

In recent decades, there has been an increasing recognition of the importance of human capital accumulation for intergenerational mobility16. More recently, interventions have been analysed according to their capacity to promote households out of poverty sustainably, so that ongoing support is no longer required.

There are a number of ways in which charitable interventions attempt to reach these objectives, with varying success according to the metrics used to evaluate them. The most common are:

- Directly transferring income or wealth to low-income people through conditional or unconditional cash or capital transfers

- Developing microfinance institutions to provide financial services to low income people, allowing them to borrow, save, or insure themselves

- Increasing productivity throughbusiness support, skills training, or coaching

The current literature seems to suggest cash transfers have a stronger track record than microfinance institutions across a range of indicators. In particular, cash transfers are better able to target the poorest, and avoid the risk of harm associated with providing loans. GiveWell explains that "the best available evidence seems to suggest that cash transfers are beneficial – increasing consumption over the short and long run – while the available evidence on microlending does not show clear positive (or negative) impact"17.

On the other hand, microcredit institutions are often profit driven companies, which may be self-sustaining in the long-run. The dual objective of these institutions however, may be problematic for donors. We tentatively suggest that, on balance, direct cash transfers are likely the best bet but the economic debate is still open and our position may change in the future.

Programs which aim to improve the productivity of the beneficiaries through business or agriculture support or direct job creation, in theory, increase income by improving productivity. We have not done a full literature review on these programs as there is little public information on charities' ability to overcome the challenges of transferring business knowledge from the developed to the developing world18.

Recently, attention also also been received by a new type of intervention: the multifaceted graduation approach. This approach aims to help the extreme poor set up sustainable self-employment activities and create lasting improvements in their well-being. It does so by delivering an integrated set of interventions, including: a productive asset grant similar to a cash-transfer, training and support, life skills coaching, temporary cash consumption support, and typically access to savings accounts and health information or services. This approach has shown promising results.19 However, we currently lack in-depth information to assess the cost-effectiveness of charities endorsing this type of approach.

2.Microfinance Institutions (MFIs)

2.1 How does it work?

Access to financial services is important as it allows people to manage the high level of risk associated with irregular income and vulnerability to outside shocks. Without access to MFIs, members of poor rural communities rely on informal institutions, which often charge high premiums or interest rates to fund short and long term consumption needs and invest in business or household items.

Borrowing in the developing world

Use of credit is widespread in the developing world. Low-income households use a variety of borrowing mechanisms to cope with risk and everyday needs for disposable income. In their Portfolios of the Poor study20, Collins et al. show that impoverished households employ complex financial tools to manage their money, many linked to informal networks and family ties. Borrowers’ lack of collateral to offer as security to banks means that moneylenders need to gather information about them and monitor their use of the money to prevent risks of willful default21. This leads to higher interest rates to compensate the cost of monitoring. It is harder for formal institutions to obtain information about the borrower than for local moneylenders who know their clients and can rely on coercive methods to ensure repayment22. This helps to explain why poorer people often only have access to informal lending mechanisms charging extremely high interest rates.

The role of microcredit

Microcredit attempts to fill the void between informal lending schemes and formal banking. MFIs use a variety of methods to reduce their monitoring costs and risk of default. This allows them to offer interest rates which are typically lower than formal institutions23.

MFIs traditionally rely on the ability to keep a close check on customers, by providing loans to groups of borrowers liable for each other’s loans24. In this group-lending model, the strong social pressure of shame as well as MFIs’ threat to cut off all future lendings in case of default help to prevent issues of adverse selection and moral hazard. The small group structure, often between people who are already acquainted, also increases the solidarity between group members who are more likely to help each other out in case of temporary difficulties to repay25.

In addition, the rigid repayment structures of MFIs concerning how and when the loan has to be repaid provide less flexibility for borrowers than informal loans but greater stability26, and reduces the administrative cost of lending which in turn lowers the interest rates. Weekly repayment schedules, as in India and Mexico27, are the norm in microlending schemes. The idea is to diminish the constraint of making a payment by imposing small amounts within easy reach of the customers28. However, it also makes it more difficult for people whose earnings tend to be unpredictable and who lack reliable ways of saving29.

2.2 Tractability

While there is a strong intuitive argument for the role of microcredit in improving the lives of the poor, the evidence suggests that MFIs have only had limited success in pulling people out of poverty30. According to the major systematic reviews of the available evidence313233, while microloans increase access to credit, they do not substantially benefit the poorest households, and have not been shown to bring about sustained increases in either income or consumption.

Are microcredit schemes self-financing?

The charitable status of MFIs is ambiguous, and their double mission - for profit on one hand, social impact on the other - can lead to unclear objectives as well as obstacles in their evaluation34. Banerjee and Duflo claim that MFIs are reluctant to gather rigorous evidence to prove their impact, claiming that if their clients come back for more, it must be beneficial to them35. But donors give to these institutions because they believe that microfinance is better than other ways to benefit the poor. If MFIs are indeed self sustaining and completely independent from donors’ generosity, there is no reason for resources to be spent on funding MFI lending schemes. If on the other hand MFIs do rely on external subsidies and donors’ support, they need to show that they actually have an impact in people’s lives, and more so than other programs competing for charitable resources.

How much does it cost?

One claim about microfinance is that a gift to an MFI gets lent out again and again, making its impact essentially infinite. However, many of the most important challenges of microfinance, such as developing effective outreach, creating incentives for repayment, and helping people to save as well as borrow, involve significant institutional expenses. Measuring the cost-effectiveness of microfinance schemes is difficult but GiveWell has attempted to estimate the potential cost of subsidising MFIs based on the available data36.

Givewell estimated that about $2.2bn of MFIs’ funds came from grants and donations in 2008 (about 19% of all funds). Since there were between 130 and 190 million MFI clients worldwide at that time, about $12 to $17 were spent in grants alone for every MFI borrower. Now suppose that MFIs expanded to cover the entire target population of 3 billion people while the annual subsidy of $2.2bn remained constant. It would then cost $0.75 per year to provide financial services to each person. In reality, it seems extremely unlikely that MFIs could expand to cover the entire target population without additional subsidy, particularly because the populations which are easiest to target effectively are likely to have been the first to be covered. We therefore expect the $12-$17 estimate to be a more accurate reflection of the average cost of providing financial services to each person.

If the $0.75 figure is taken as reflective of the potential cost of microfinance, the cost of providing five people with a year’s worth of financial service would be about the same as giving deworming drugs to 14 childrenleading to about one extra year of school attendance37. However, we feel that the true cost is likely to be closer to $12-$17, indicating that a better comparison would be deworming 300 children, leading to about 20 extra years of school attendance. A donor could therefore choose between providing five people with four extra years of schooling each, or providing them each with a single year of financial services.

Until recently, robust evidence was unavailable

Although a number of studies have been conducted on the impact of microcredit, they have suffered from a number of methodological deficiencies38. Even those attempting to address the challenge of mistaking correlations for causation failed to prove rigorously that the observed links between prosperity and loans were due to an improvement in living conditions thanks to a loan rather than to borrowers being better off to begin with. For instance, whilst some studies found positive effects of microcredit on labour supply, school enrolment, expenditure per capita and non-land assets39, others failed to replicate the results and criticised the methodology and data involved40.

Recent RCTs find evidence of low impact

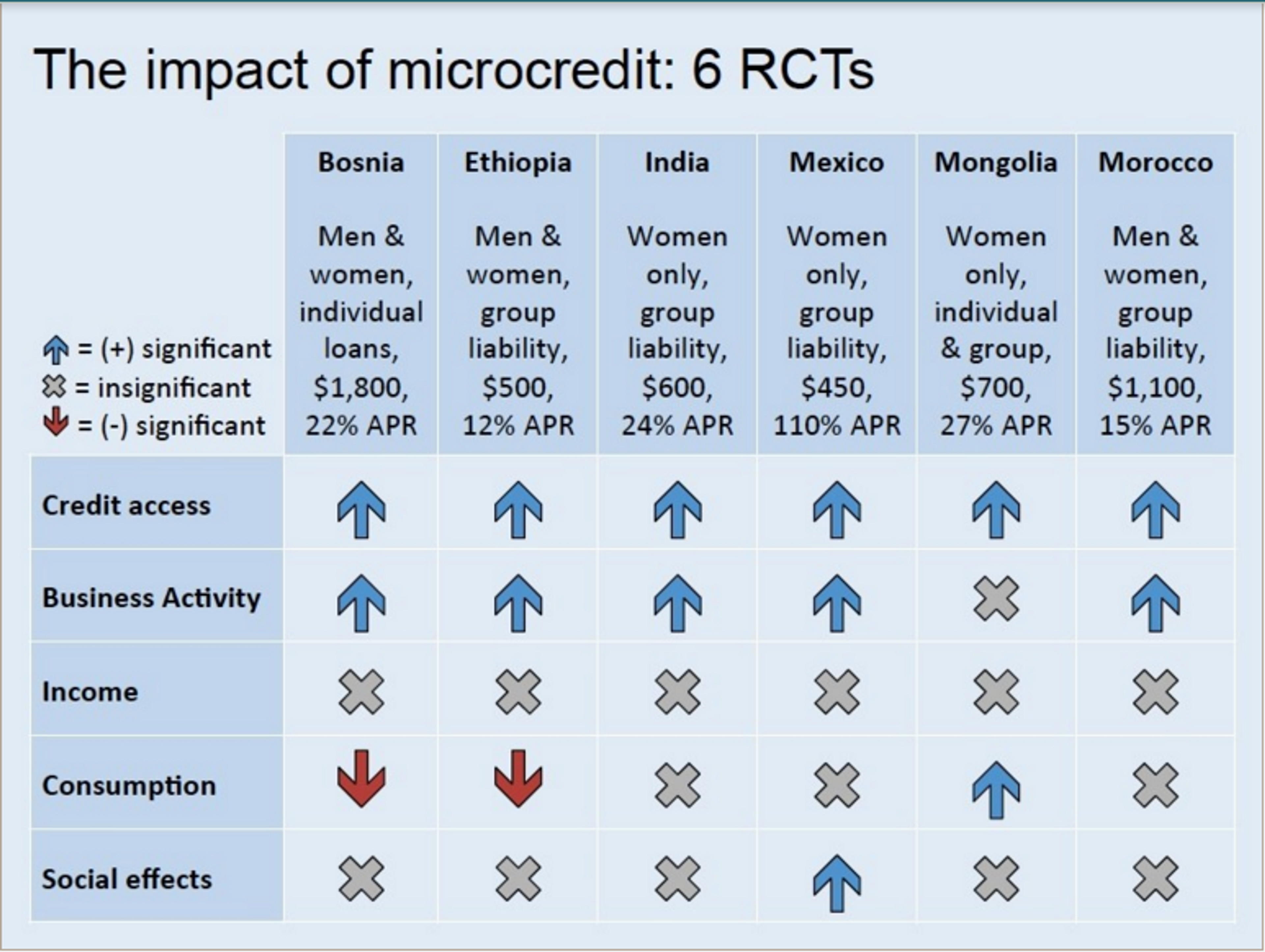

In recent years however, there have been an increasing number of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) on the impact of microcredit. Studies from the past few years include RCTs in a variety of countries, including Bosnia-Herzegovina41, Ethiopia42, India43, Mexico44, Mongolia45 and Morocco46. These studies are relatively consistent in their findings and do not produce strong evidence that effects vary substantially across different settings47. On the whole, they have found no statistically significant evidence of an increase in socio-economic indicators such as income, consumption, health, and education (see Figure 2). However, it would be hasty to draw strong negative conclusions from these results. First, all the studies found that microcredit improved access to credit (rather than crowding out alternative funding sources). Second, there was substantial heterogeneity between the null results, which often had large error bars48. Overall, the jury is still out on the impact of microcredit, but the current evidence seems to suggest that, while microloans are successful at providing access to credit, this does not necessarily translate to improved outcomes.

Figure 2: Summary of the findings of 6 RCTs on microcredit. Source: Center for Global Development49

Credit access

All the studies find that extending access to microcredit does not result in crowding out other lending sources. That is to say that MFIs are, to some extent, achieving their primary objective of increasing access to credit. Between 2006 and 2007, for example, the MFI Al Amana opened around 60 new branches in rural areas which had not been exposed to microcredit before the program was launched50. In India, the share of households taking up informal credit at high interest rates goes down by 5.2 percentage points in the treatment areas51, which suggests a substitution of expensive borrowing with cheaper MFI borrowing. Although there is some evidence of substitution among different credit types52, with the Mongolia study finding evidence of 20-25% crowd-out of other formal credit53, the strongly positive impact on access to credit means that people who would not have obtained loans otherwise are now able to borrow and invest in ways they could not have done before.

Despite the lack of transformative effects (see Social effects), microfinance can be seen as a tool to give people more freedom in their choices and the possibility of being more self-reliant. In his comprehensive book on microfinance Due Diligence, Roodman explains that the poorest people in the world face considerable financial uncertainty; by empowering them to manage their own lives, microloans as well as other financial instruments promoted by MFIs do have an important role to play54.

Nevertheless, these results are weakened by surprisingly low take-up rates55. In the study led with the MFI Al Amana in rural Morocco, for instance, less than a sixth of eligible families were interested in a loan56. This could suggest that, while financial constraints do affect some households, they may not be binding for the majority. Another possible explanation is that the small amounts lent, with interest rates and a regular repayment schedule, are not sufficient to solve households’ intertemporal budget constraint57. Finally, risk aversion and a lack of knowledge on how to invest the loan might also explain why some households are reluctant to accept loans when they are offered to them.

Business activity

A common conception of microfinance is that, by giving households the ability to borrow, microcredit helps them start or expand small businesses. There are many anecdotal success stories of business owners who have benefitted from these loans58. Banerjee et al.’s review concludes that “[...] each study finds at least some evidence, on some margin, that expanded access to credit increases business activity,”59 (see Figure 2) and in Hyderabad (India), 15 to 18 months after the introduction of microfinance, microcredit clients were found to invest more in the businesses they had or those they started, and there were small increases in average profits60.

However, this expansion was mostly driven by the businesses who already made the most profit before the introduction of microcredit, whereas the median marginal new business was both less profitable and less likely to have even one employee in treatment than in control areas61. Apart from a slight benefit for existing businesses, it seems that microloans have little impact on entrepreneurship, a conclusion which is consistent across the different studies. A possible explanation is that because of the small amounts given out and the regular repayment schedule, microloans might not provide a good tool for the long term and risky investment required to grow a small business62.

Another apparent indicator that microloans “work” and help businesses thrive is that defaults on loans are very rare. This suggests that recipients might be able to make substantial profits far beyond their original investment63. However, these high “repayment rates” are also misleading. GiveWell explains that unless the MFIs are very specific about how the repayment rate is computed, this figure is highly subject to interpretation. They show that, the way they are currently being reported, a 99% “repayment ratio” can be consistent with a default rate of over 30%64. For example, some definitions of repayment rates ignore loans that have been written off, even if they include defaults. In other cases, what is reported is the percentage of repayment on loans outstanding, which includes loans that aren’t yet due65. This means that an MFI can inflate its “repayment rate” by giving out new loans. In addition, because of the strong social pressure to repay the loan, necessary to the viability of lending schemes, repayment does not imply commercial profit: people have to find ways to repay their loans even if they do not make significant profits from their business.

Finally, loans are not exclusively used for business purposes. In their 2011 study in Mongolia, Attanasio et al. find that “although the loans provided under this experiment were originally intended to finance business creation, [...] about one half of all credit is used for household rather than business goals”66. Using the extra resources for consumption purposes is not necessarily a bad thing, but it contrasts with the common understanding of the way microfinance charities help the poor to come out of poverty.

Duflo and Banerjee offer one explanation. They suggest that, for the most part, the micro-enterprises set up by people living in poverty are small, unprofitable businesses undifferentiated from the many others surrounding them67. Many of the poorest people in the world run their own businesses: a study of eighteen low-income countries finds that on average, 44% of the extremely poor in urban areas operate a nonagricultural business68. In fact, becoming an entrepreneur is often seen as a way to make extra income when conventional employment is unavailable rather than something to aspire to69. The median business never grows to the point of having paid staff, and although the marginal returns are high at first, its growth potential tapers off fast70. They conclude that given that their firm is destined to stay small and never make much money, the poor direct their attention and resources to other things.

Income and consumption

None of the six recent RCTs finds statistically significant increase in income71, arguably the best indicator of poverty reduction. Four of the studies also measure household consumption, and again no statistically significant increase is found. In fact, there is even a reported decrease in consumption in some cases, and these results remain true when other proxies for living standards are used, such as food consumption72. The Morocco study for instance analysed levels of consumption two years after loans were received and found no statistically significant increase73.

The distribution of households’ use of the supplementary income varies from study to study, but one robust finding is the decrease in discretionary spending such as temptation goods and entertainment74. However, another finding on expenditures is the lack of significant increases in other types of spending, such as health and education75. This suggests limited impact on long term economic prospects and improvements in human capital.

In Mongolia, women who obtained access to microcredit often used the loans to purchase household assets, in particular large domestic appliances76. Attanasio et al. find a substantial positive effect on food consumption, particularly of fruit, vegetables, dairy products and non-alcoholic beverages77. A relation also appears between business investment and consumption. In the India study, Banerjee et al. find that households with a high propensity to start a new business reduce their consumption in the short term and use microcredit to deal with the fixed costs of starting a business, while those with a low propensity increase their current consumption against future income78.

Social effects

The studies do not find clear evidence, or even much suggestive evidence, of substantial improvements in social indicators79, although we should note the difficulty of measuring such impacts accurately80. Two particularly important outcomes are child schooling and female empowerment.

Child Schooling

Each of the six studies estimates treatment effects on schooling, and generally found inconclusive results. In fact, the Bosnian study actually found a significant decline in school attendance among 16–19-year-olds81, although this may be due to measurement error.

Female Empowerment

One of the major claims of MFIs is that microfinance contributes to female empowerment82. Many microlending schemes are directed at groups of women and explicitly aim to help them build up a business of their own. MFIs’ focus on lending to women is partly a consequence of commercial interest, given women’s higher loan repayment rates, but some development research also suggests that women tend to put more of their earnings back into the home or into services for their children (health, education, etc)83. Serving women, therefore, seems beneficial to both the business and the social impact missions of microcredit.

Although some studies find positive but non-uniform effects on female empowerment, other systematic reviews find they can neither support nor deny the claim that microcredit is pro-women84. There are obvious effects on female employment but, of the six recent microfinance studies reviewed, three find no effect on female decision-making power and/or independence within the household, whilst three estimate some effect85 - the RCT in Mexico, for instance, finds some hints of positive effects on female empowerment and well-being86. Overall, there is some evidence that female employment has increased as a result of microcredit but it is uncertain whether this has led to increased levels of female empowerment.

Benefiting the poorest

It is a common concern within the microfinance community that interventions and resources aimed at reducing poverty should target the poorest members of the population, and several methods have been used to ensure that microloans reach the very poor87. Nevertheless, participants in microfinance programs are on average richer than the population in the same area, and few MFIs reach the customers at the very bottom of their national poverty scale. In contrast, unconditional cash transfers do reach the poorest people (see report below). The number of poorest microfinance customers fell for the third straight year in 2013, with 114 million out of the 211 million worldwide living on less than $1.90/day88. In Bangladesh, where MFIs are strongly focused on serving the very poor, MFI concentration is highest among the second poorest quintile but lowest among the poorest quintile89.

Even interventions targeting very poor clients often fail to reach the poorest in their area. This conclusion is supported by a 2014 study of community-managed methods particularly suited for people living on less than a dollar a day, the Village Savings and Loan Associations (VSLA)90. Such microfinance models count more than two million members worldwide, but the randomized controlled trial on a VSLA scheme in northern Malawi finds that the targeting is regressive, with a higher percentage of nonparticipant households participants below the poverty line than for participant households. A possible explanation could be that extremely poor people may prefer not to borrow because they think debt is more likely to hurt them91. The strong capacity for resources, involvement and skills required from microloans borrowers also puts into question the ability of the poorest to participate92.

Potential for harm

Unlike other charitable interventions, microloans come with an obligation to repay. They therefore have a chance of hurting recipients by encouraging indebtedness at high interest rates. The high “repayment rates” are not clear proof of recipients’ ability to safely repay their creditors, and dropout rates are substantial, “averaging 28% and often exceeding 40%” according to a 2009 GiveWell report based on MixMarket data93. This means that clients who seem to be paying back their loans could be pressured into doing so despite low resources, and then drop out of the program.

In practice, there is little evidence that microfinance causes harm on average: none of the six studies find evidence of harmful effects94, including in Mexico where the annual interest rate averages 110%95. However, as we have mentioned above, null results looking at averages ignore potential heterogeneous effects and may indicate that some people benefit and others are hurt from access to loans. Donors would rightly be concerned about funding an intervention which may actually cause harm to some.

2.3 Neglectedness

Microfinance has received significant attention and resources in the past few decades96. Public funding especially has contributed to build microfinance institutions that are attractive to international and local private lenders. As of December 2013, public and private lenders have committed a total of over $31 billion to financial inclusion97 - a broader concept than microcredit, which includes a variety of other services (such as insurance, savings and payments services)98 and reflects a better understanding of the needs for financial services of the poor99. MFI benefits from support from charities and development finance institutions (DFIs) with a poverty reduction objective, as well as private investors who use it to “diversify their investment portfolios while doing good”100.

This raises questions over whether there is room for more funding, and even in some areas whether additional funding would result in overlending and actually cause harm, as may have been the case in Peru101.