Dementia (Alzheimer's Disease)

Giving What We Can no longer conducts our own research into charities and cause areas. Instead, we're relying on the work of organisations including J-PAL, GiveWell, and the Open Philanthropy Project, which are in a better position to provide more comprehensive research coverage.

These research reports represent our thinking as of late 2016, and much of the information will be relevant for making decisions about how to donate as effectively as possible. However we are not updating them and the information may therefore be out of date.

Cause Area: Dementia (Alzheimer's Disease)

The following cause-level investigation was completed as part of a bespoke report for an individual donor. Giving What We Can has not prioritised dementia as a primary cause area and our investigation to date has not suggested a high level of cost-effectiveness or of neglectedness. In addition, for this report we only considered charities working within the United Kingdom. Although anti-tobacco advocacy groups in general are likely to be one of the more cost-effective methods of reducing dementia prevalence, they may be a great deal more or less cost-effective than Action on Smoking and Health UK. Given this, the following report may provide some useful insights into dementia as a cause area, but we do not recommend donations in this area or to this charity as one of the most effective ways to improve overall human health.

Summary

Dementia, particularly Alzheimer’s disease, constitutes a large portion of the burden of disease and total mortality in high-income countries (HICs) such as the United Kingdom (see Section 2). However, no effective treatments are currently available for Alzheimer’s disease nor is there a clear understanding of the causal mechanism by which the disease develops (see Sections 1 and 3).

Nevertheless, there is a large body of evidence linking the disease to tobacco use, and it has been estimated that smokers have a 40-79% greater probability of developing Alzheimer’s disease (see Section 4). This indicates that mortality and morbidity due to the disease might be greatly reduced by reducing the number of people who smoke, and this led us to evaluate the UK advocacy charity Action on Smoking and Health (ASH), given its relative cost-effectiveness.

It is likely that there are opportunities in the developing world to more cost-effectively reduce Alzheimer’s prevalence through tobacco control, particularly due to the large projected increase in prevalence over the coming decades (see Section 2). However, for this report we restricted our scope to domestic UK charities in accordance with the donor's wishes.

Nonetheless, we are quite confident that, of the charities operating in the UK, ASH is one of the most cost-effective in reducing the incidence of Alzheimer’s disease and improving health. Although it works through indirect means, through tobacco control and also through lobbying, and although its cost-effectiveness does not exceed that of our top recommended charities, we do believe that the expected impact of ASH’s activities on Alzheimer’s morbidity and mortality are quite considerable. This is due to the consistently high quality of its implementation, how well-placed it is to effectively lobby and advocate for tobacco control, its past successes (which were both sizeable and also achieved on quite a low budget), its strategic approach to future activities, and the projected cost-effectiveness of those future activities.

We estimate that for every £1 spent throughout the year, ASH’s public advocacy is able to reach 281 viewers through the news media as well as 1,079 online viewers. In the past, ASH’s activities have reduced annual deaths at a cost of £283,000-£525,000 per Alzheimer’s death per year (£14,000-£26,000 per death prevented over 20 years, undiscounted). We estimate that, in the future, ASH’s activities over the next 5 years may continue to do so at a cost of £531,800-£985,000 per Alzheimer’s death per year (£26,600-£49,200 per death over 20 years, undiscounted). This figure improves significantly if other ill health due to smoking, such as lung cancer, stroke and other health conditions would also be included, falling to £30,600 per death per year and £1,800 per DALY per year (£1,500 per death and £90 per DALY over 20 years, undiscounted). Overall, tobacco control and anti-smoking campaigns are some of the most cost-effective health interventions available in the United Kingdom, with some estimates suggesting that they might as low as £49-91 per additional quality-adjusted life year gained.1 For Alzheimer’s disease specifically, these figures indicate that ASH’s cost-effectiveness is not as high as for the top charities working in developing countries, but it still appears to be one of the best opportunities for reducing the burden of Alzheimer’s disease and improving overall health in the UK.

1. What is Alzheimer’s disease?

Alzheimer’s disease is the most common form of dementia, constituting 60-70% of cases and the bulk of its disease burden,23 and will hence be the primary focus of this report. However, another relatively common form is vascular dementia, which is responsible for 17% of cases.4 Together, and including mixed cases, Alzheimer’s and vascular dementia account for close to 90% of all dementia cases.5 Also, notably, the risk of both Alzheimer’s and vascular dementia is increased by smoking by a similar amount (see Section 4). Thus, the scope of this report will be largely restricted to these two forms, with a particular focus on Alzheimer’s.

Alzheimer’s disease is characterised by a progressive decline in cognitive and motor function, which begins with minor symptoms such as memory loss but later results in severe brain damage and death.678910 However, research into the disease has been somewhat inconclusive thus far. As yet, the exact biological changes which cause Alzheimer’s are unknown, as are the reasons for it progressing more quickly in some patients than in others, and also how it might be prevented or effectively treated.111213 It has been observed that the brains of Alzheimer’s patients have reduced mass, larger cavities for cerebrospinal fluid production, a large percentage of dead neurons, and much smaller mass in areas related to memory.1415 Two abnormal protein structures have also been observed in the brains of Alzheimer’s patients - amyloid plaques and tau tangles - though research has not established the exact causal relation between these structures and the disease itself.16 Notably, these physical changes begin approximately 20 years before symptoms are exhibited.17181920

Commonly observed symptoms include: memory loss; impairment of problem-solving and planning ability; difficulty in performing even familiar tasks; confusion regarding location and time; loss of visual comprehension and spatial reasoning ability; difficulty with speaking and writing; impaired judgement; social withdrawal; mood and personality changes, including depression.212223242526

It is believed that, in a small proportion of patients, Alzheimer’s disease develops due to specific genetic mutations and that individuals who inherit this mutation have a 95% likelihood of developing the disease.2728 However, this accounts for only 1% of all cases.2930 There is also some evidence linking Alzheimer’s disease more broadly to the herpes simplex virus and several different types of bacteria, although the exact causal relation is not yet fully understood and this remains the focus of ongoing research.313233

For Alzheimer’s cases more generally, although no specific causes have been established, a variety of probable risk factors have been identified:34

- family history - those with parents and relatives who experienced Alzheimer’s are more likely to contract it;353637

- age - the vast majority of those diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease are over the age of 65;3839

- **cardiovascular disease and poor cardiovascular health404142434445464748 - particularly due to and exhibited by smoking, hypertension, obesity, and diabetes - which, unlike the other factors listed here, is supported by not only correlational but also causal evidence;4950

- traumatic brain injury;51

- lack of social and cognitive engagement throughout life;5253545556

- education - lower levels of education have been linked with increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease later in life;5758

Of these risk factors, many seem to correlate, but cardiovascular problems are the only factor which is clearly causal.[^fn-a]59 In addition, cardiovascular problems are likely to be the most easily preventable.

2. How does it affect people?

In addition to the symptoms mentioned in Section 1, which may cause considerable suffering for Alzheimer’s patients and their families, the disease is ultimately fatal.60

Alzheimer’s is a significant contributor to global mortality, accounting for 3.02% of all deaths (see Figure 1 below)61 - this equates to 1.66 million deaths each year.62 919,000 of these deaths occurred in developed nations while only 737,000 occurred in developing nations.63 This represents a sizeable overrepresentation of developed nations as the total population size of developed nations is significantly smaller - for comparison, Alzheimer’s causes only 1.76% of all deaths in developing nations, while it causes 7.02% of all deaths in developed nations.64 Thus, it is somewhat accurate to describe Alzheimer’s as primarily a developed-world disease. However, Alzheimer’s prevalence is expected to increase considerably in developing countries over the coming decades (see below).

Figure 1: Annual deaths due to Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia, as a proportion of total global mortality.65

As for disability-adjusted life years, Alzheimer’s disease accounts for a lower proportion, only 0.91% of total DALYs incurred (see Figure 2 below), because it primarily affects those over the age of 65 and so a death caused by Alzheimer’s does not result in as many years of life lost as, say, the death of an under 5 year old due to malaria or a middle aged person dying due to heart disease.66 This percentage of DALYs rises to 2.84% in developed nations and falls to only 0.55% in developing nations. In comparison, malaria accounts for 2.68% for DALYs globally and 3.18% of DALYs in developing nations,67 suggesting that the impact of Alzheimer’s on morbidity and mortality may be comparatively small.

Figure 2: Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) incurred by Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia each year, as a proportion of total disease burden.68

Alzheimer’s and dementia also result in a considerable economic burden. Worldwide, $818 billion in healthcare costs associated with dementia were incurred in 2015.69 Approximately $200 billion of these were in the United States,70 and £26 billion (approximately $37 billion) in the United Kingdom each year.71

The prevalence and costs of dementia are projected to increase greatly over the coming decades. It is estimated that neurodegenerative diseases such as these will surpass cancer to become the second most common cause of death worldwide by 2040.72 By 2030, dementia cases will have almost doubled from 46.8 million in 2015 to 74.7 million, and continue to increase to 131.5 million in 2050.73 Global economic costs are also expected to increase greatly, reaching $2 trillion by 2030.74

Notably, much of the increase in prevalence of dementia over the coming decades is expected to occur in low and middle income countries (see Figure 3). This indicates that interventions which focus on dementia prevention and which take some time to have an effect, such as tobacco control (see Section 4), may therefore have greater impact in developing countries. Nevertheless, at a domestic level, dementia appears to be comparatively tractable and high-impact due to its current high prevalence. Also, tobacco control and anti-smoking campaigns are some of the most cost-effective overall health interventions available in the United Kingdom, with some methods costing only £49-91 per additional quality-adjusted life year gained.75 This surprisingly low cost, combined with the high prevalence of dementia in the United Kingdom (at 8.46% of all deaths),76 has led us to recommend a domestic British charity for this cause area specifically. It is worth noting, however, that the similar tobacco control interventions may be even more cost-effective when conducted in developing countries and may prevent many more cases of dementia, particularly in regions that are poorly equipped to properly care for dementia patients.

Figure 3: Predicted number of dementia cases from 2015 to 2050, separated into HICs and LMICs.77

3. How can you address the problem?

Based on the current scientific understanding, there are few proven interventions to treat or prevent Alzheimer’s disease, and it is impossible to predict with any accuracy whether any particular intervention will interrupt the causal mechanism that results in any particular patient contracting the disease and later dying from it. Broadly, potential interventions to reduce the incidence of Alzheimer’s can be categorised into: direct treatment of the condition; activities which focus on the prevention of Alzheimer’s cases; and further research into the disease. Of these, there does exist one intervention which we are fairly confident may greatly reduce the probability of contracting the disease and, thereby, cost-effectively prevent a large portion of Alzheimer’s cases - namely, smoking cessation, which will be discussed below.

Treatment

At present, treatment is not a promising form of intervention. There exist only six drugs which have been approved by the United States’ Food and Drug Administration for Alzheimer’s treatment and none of these are able to slow down or halt the progress of the disease in damaging neurons and resulting in death.78 Each of these drugs has been shown to be effective only in temporarily alleviating symptoms of the disease, and only for a minority of patients.7980 In addition to these, there exist several nonpharmacologic treatments which have been observed to have some effect. These include general exercise, music therapy, reminiscence therapy, and others.818283 Again, these therapies do not slow down or halt progress of the disease but merely alleviate symptoms such as depression, memory problems, and agitation. They are also lacking in clear evidence, and few have been subjected to randomised control trials.84858687 Thus, neither pharmacologic or nonpharmacologic treatment is promising as an effective health intervention.

Prevention is more promising. From above, there is evidence that certain characteristics do correlate with incidence of Alzheimer’s disease: family history;88 age;89 poor cardiovascular health, as contributed to by smoking, hypertension, obesity, and diabetes;90 tobacco use in general (in addition to its effects specifically on cardiovascular health);, traumatic brain injury;91 lack of social and cognitive engagement throughout life;9293 and low levels of education.94 Not only is it unclear if several of these are causally linked with the disease or simply correlated, but most of them are also unlikely to provide cost-effective means of reducing the disease burden of Alzheimer’s. For example, greatly improving the education system of an already-developed nation is extremely costly. Reducing the incidence of traumatic brain injury would be quite a difficult endeavour, and potentially not at all neglected, with strict laws already in place in the UK regarding occupational health and safety,95 the mandatory use of motorcycle helmets,96 and so forth. Improving social and cognitive engagement over individuals’ entire lives would likely be extremely costly and intractable to implement (as well as it being least likely to be causally related), although the co-benefits might be considerable. Intervening on family history, that is genetics, is not possible. Anti-aging research could have considerable co-benefits, but does not seem to be very tractable as it requires more basic research at this point.97 This leaves only the improvement of cardiovascular health and the reduction of smoking. The latter might be most easily achieved through tobacco control and smoking cessation campaigns. The former might be achieved through combating obesity, diabetes, hypertension, poor diet and, again, tobacco control.98 Of the available interventions in these areas, tobacco control and broader smoking cessation appear to be the least costly (even in developed countries) and also most easily tractable. See Section 4 for an indepth discussion of this.

Research

Research is another area which initially appears promising. After all, there is still a lack of effective treatments available and a lack of evidence in favour of many cost-effective methods of prevention (with the exception of tobacco cessation).99100 Further research into Alzheimer’s disease and potential interventions is the only method by which such treatments and prevention methods might be developed. Hence, if there do exist other effective methods of treating Alzheimer’s and dementia then research is first necessary in order to develop them. However, the outcomes of research are highly uncertain and, if cost-effective interventions already exist, then there is very low probability that more cost-effective interventions will quickly arise from additional research. As will be addressed below, tobacco control may already provide the opportunity to cost-effectively reduce the burden of Alzheimer’s disease, and thereby of dementia in general, at a potentially net-neutral cost (see Section 4.2). Even lobbying for tobacco control may reduce the burden of Alzheimer’s at a rate potentially as low as £14,000-£26,000 per life saved over 20 years, undiscounted (see Section 4.4). Alzheimer’s research, which focuses largely on rather costly treatments and diagnostic methods,101102103104 is unlikely to uncover interventions which reduce the disease burden at a comparable cost at any point in the near future. Even if cost-effective treatments are discovered through research, the cost of delivering those treatments aggregated with the substantial cost of research is unlikely to be less than the currently quite low cost of prevention through tobacco control.105 Notably, there is promising work being done on potential methods of vaccination, but it is still extremely unclear how efficacious this might be,106 and the likely cost of the therapy per QALY gained is still prohibitive.107

In addition, it is questionable whether Alzheimer’s research is sufficiently neglected for additional donations to do more good here than for other conditions which have a greater disease burden - dementia in general accounts for only 0.91% of global DALYs while, for example, back pain accounts for 2.94%, migraines for 1.18%, diabetes for 2.27%, and HIV for 2.84% (with prevalence currently increasing at 5.1% per year).108 $800 million is spent on dementia research each year by G7 nations.109 This is a larger allocation per DALY than for tropical diseases (which, along with other diseases which make up 90% of the global disease burden, typically receive less than 10% of research funding),110 migraines (only $13 million per year in the United States, for instance),111 diabetes and back pain which are not even widely recognised as warranting focussed research programmes, and even HIV, which is considered quite well-funded (at $1.25 billion per year).112 In particular, given the recent large increases in public funding of dementia research in the United Kingdom and internationally (with annual UK spending doubling between 2010 and 2013 to £74 million,113 the establishment of the $100 million Dementia Discovery Fund by G8 health ministers,114 and the UK government’s £300 million commitment to further research115), it seems very unlikely that additional private donations to dementia and Alzheimer’s research will have a high marginal impact, particularly in comparison to conditions which receive less funding but also in comparison to existing prevention strategies such as tobacco control.

4. Tobacco control

There is a growing body of evidence supporting the claim that tobacco use, and secondhand smoke, greatly increases Alzheimer’s and dementia risk.

This may be through several different mechanisms. Tobacco use increases the levels of homocysteine in the body, which then increase the risk of neurological changes associated with dementia. It also increases oxidative stress, which has also been linked to Alzheimer’s disease.116 Most importantly, smoking impacts negatively on cardiovascular health and also contributes to higher incidence of diabetes and stroke.117118 Each of these is a major risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease, and dementia more broadly, but cardiovascular health specifically has been suggested to be causally linked to dementia incidence (based on a natural experiment looking at reduction of alcohol taxes in Finland).119120

A variety of extensive studies and meta-analyses have established empirically that current smokers increase their risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease by between 40% and 79%.121122123124125 Other research has indicated that high-consumption smokers also have a greater risk of Alzheimer’s later in life compared to low-consumption smokers, increasing their chances of Alzheimer’s by roughly 100% (118% for medium smokers versus 140% for heavy smokers).126127128 There is also a sizeable body of evidence of a clear dose-response relationship between tobacco exposure and Alzheimer’s risk, indicating that incremental increases in exposure are associated with increases in the risk of contracting the disease.129130131132 For vascular dementia, it is much the same case, as smoking is estimated to increase risk by 35-78%.133134

It is estimated that one third of all cases of dementia would be prevented if the basic risk factor of poor cardiovascular health were addressed by completely eliminating smoking, poor diets, excess alcohol consumption, lack of exercise and excess weight.135 This may be overly ambitious, but computational modelling has also estimated that dementia risk would reduce by 2% for every 5 percentage point reduction in tobacco use in developed countries (with a low estimate of 1.86% and a high estimate of 3.45%).136137 The World Health Organisation estimates that 14% of all cases of Alzheimer’s worldwide may be attributed to smoking, and hence potentially preventable.138 Assuming that this percentage is consistent with the percentage of mortality and morbidity due to smoking, this indicates that smoking results in 232,000 dementia deaths per year and 3.11 million DALYs (of a total of 1.66 million deaths and 22.24 million DALYs),139 all of which might be prevented through smoking cessation.

4.1 How does it work?

Among the most effective large-scale interventions for tobacco control are those available to national governments - taxation of tobacco, health education, restrictions on sales, advertising and packaging, and various other legislative methods - although awareness campaigns which reach a wide audience may also be highly effective. For private philanthropists, it is therefore likely that the greatest opportunities lie in funding lobbying and advocacy efforts, as well as in the funding of awareness campaigns to curb smoking uptake.

4.2 Tractability and cost-effectiveness

Tobacco control may be tractable or intractable in two distinct senses: tractable in that there exist highly effective policies or initiatives which can be implemented (and which have not already been implemented, such that there remain simple improvements which may be made); and intractable in that lobbying efforts and awareness campaigns by their very nature, might not succeed in leading any changes in policy or in general awareness.

Reducing smoking through tax increases, thereby increasing cigarette price, has been shown to be quite tractable on a governmental level, particularly when it comes to reducing smoking amongst young people.140141142143 A report by the World Bank estimated that for every 10% increase in cigarette cost, tobacco consumption would drop by 4% in high-income countries such as the UK.144145146 Young people, who obtain the greatest benefit from quitting, are also more likely to quit and less likely to start when prices are high.147 The WHO therefore recommends that excise taxes should account for 70% of cigarette cost.148

Initially, it appears that tobacco control may not be sufficiently tractable in HICs due to existing regulations and the crowdedness of public health relative to LMICs. Indeed, the UK already has mandatory standardised packaging for tobacco products,149150 laws prohibiting smoking in almost all enclosed public spaces,151152 and a tobacco duty of 16.5% of retail price, plus £3.79 per pack of 20, for cigarettes153 which is applied alongside 20% VAT. Tobacco manufacturers have argued that this is much higher than nearby European countries, and that this already constitutes 77% of the cost of a typical pack of cigarettes154 although, excluding VAT, the excise taxes appear to still be only approximately 60% of total cost - slightly lower than is recommended by the WHO.

Nevertheless, for Alzheimer’s prevention specifically, lobbying and government policy impact on a national (or sub-national) level and hence will generally be more tractable in nations with high Alzheimer’s prevalence - that is, HICs such as the UK. As shown in Figure 4 below, the disease burden of dementia in many HICs (in DALYs per 100,000 population each year) is roughly 10 times higher than many LMICs. The UK rate, for instance, is 4.5 times higher than the developing world average (877 versus 193 DALYs/100,000).155 Even in age-standardised figures it is still considerably higher (448 versus 348 DALYs/100,000).156 This indicates that, even though Alzheimer’s prevalence in developing countries is set to increase enormously alongside life expectancy over the coming decades (see Figure 3 in Section 2 above), it still disproportionately affects HIC such as the UK and is likely to continue to. Thus, the tractability of Alzheimer’s prevention, through tobacco control or otherwise, is unlikely to be a great deal less in HICs.

Figure 4: Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) incurred by Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia each year per 100,000 people, by location.157

In addition, there is also still an opportunity for further progress (or for a reversal of progress). 2015 marked the end of the UK government’s Tobacco Control Plan,158 so there is currently a gap in the government’s strategy for the future and an excellent opportunity for advocacy groups to push for a new strategy which minimises mortality and morbidity as much as possible (however it also poses an opportunity for pro-tobacco lobbying to do the opposite). This suggests that the issue is particularly tractable at present.

In addition, there are a variety of promising policies which have yet to be implemented, as recommended by ASH, and these include159:

- The announcement of specific goals, such as the reduction of smoking prevalence to 5% in all socioeconomic groups by 2035 (there is currently substantial inequality in smoking rates, with routine and manual workers smoking more than twice as much as professionals and managers);160

- Greater funding of mass media campaigns, which are particularly neglected (see Section 4.3 below);

- A direct levy on tobacco companies to fund smoking cessation services and other tobacco control initiatives;

- Requiring tobacco companies to make their sales data, marketing strategies and lobbying activities public;

- Increased funding for the NHS’s Stop Smoking Services, and improvements in the availability of this service to all smokers, particularly to lower socio-economic groups;

- Including instruction on smoking cessation in medical training;

- Regulation of the market of nicotine products which do not contain tobacco (e.g. ‘vaping’), in order to maximise their availability to smokers for smoking cessation and minimise the chance of uptake by non-smokers;161

- Further increasing the excise tax on tobacco products, including an increase in the tax escalator to at least 5% above the rate of inflation;

- Removing the tax differential between manufactured and hand-rolled cigarettes;

- A positive licensing scheme for all tobacco retailers;

- Consultation about the prohibition of smoking in select outdoor areas; and

- Warnings and possible reclassification for films and television shows containing tobacco use.

ASH claims that such policies would likely be sufficient to reduce smoking among adults to 13% by 2020 and 9% by 2025, and to achieve the goal of reducing smoking among all socioeconomic groups to less than 5% by 2035.162

As for the lobbying required to bring such policy about, it appears that it may be quite tractable. Of course, the tractability of lobbying may vary enormously depending on the exact policy being lobbied for, the exact methods used, the reputation and connections of the charity doing the lobbying, and many factors which are impossible to accurately predict. For this, therefore, there is a great deal of uncertainty. Due to this, and the potentially enormous differences between charities lobbying on the same issue, it is much more useful to consider the tractability and effectiveness of individual charities. The charity we recommend in this report, Action on Smoking and Health, does appear to find a great deal of traction in its lobbying work and has a number of demonstrated past successes - for instance, the implementation of standardised packaging in March of 2015 was recognised by the Shadow Public Health Minister as largely the result of ASH’s work.163164 See Section 4.4 for further details.

Mass media awareness campaigns also appear to be highly tractable, given their extremely high cost-effectiveness and current neglectedness (see Positive Wider Impacts and Section 4.3 below).

Cost-effectiveness

Based on the available evidence, tobacco control and smoking cessation activities appear to be quite cost-effective for reducing the prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease, as well as for improving health more generally. However, there is the additional question of whether lobbying for such policies and activities is also cost-effective, which is highly dependent on the organisation in question and will therefore be discussed in Section 4.4.

It has been estimated that dementia risk reduces by 2% for every 5 percentage point reduction in tobacco use in developed countries, although this is quite uncertain and also based on data from the United States rather than the United Kingdom.165 Based on our analysis166 of the more comprehensive studies mentioned above, which estimated that smokers have a 40-79% greater chance of dementia than non-smokers, the estimated impact of a 5 percentage point reduction in tobacco use ranges from a 1.86% to a 3.45% reduction in dementia prevalence, morbidity and mortality. This equates to a case of dementia being prevented each year for every 109-202 smokers who quit, a death due to dementia being prevented each year for every 1,896-3,511 smokers who quit, and one DALY averted for every 167-310(distributions shown below in Figure 5).166(None of this includes health impacts other than dementia.) This is extremely useful as it allows us to estimate the reduction in dementia prevalence for any reduction in smoking.

Figure 5: Modelled distributions for, on average, the number of UK smokers needed to quit to prevent a case of dementia, a death due to dementia, or a DALY due to dementia (generated with the assistance of Guesstimate.com).

Given that tobacco consumption would drop by 4% for every 10% increase in cigarette cost (through taxation or otherwise),167168169 we can estimate that every 12.5% rise in the cost of cigarettes would result in approximately 2% fewer cases of dementia (or 1.86-3.45% by our own modelling) and presumably a reduction of approximately 2% in both morbidity and mortality due to dementia, although this is all with a high degree of uncertainty. For the UK, where there are 559,000 DALYs and 49,350 deaths due to dementia each year,170 this would equate to roughly 11,200 DALYs and 987 deaths averted each year (or 10,400-19,300 DALYs and 920-1,700 deaths). However, a 12.5% higher cigarette cost due to taxation is likely to last more than one year and, over the first 20 years, would potentially result in 19,740 lives saved and 223,600 DALYs averted (or 18,390-34,060 lives and 208,400-385,900 DALYs; also, all estimates undiscounted - see below). Of course, this is at a net-negative cost to government but a significant, but difficult to estimate, cost to those who continue to smoke. Therefore, a cost-effectiveness analysis is difficult to perform. However, the WHO claims that a tax rate of 70%-of-total-cost is optimal, so it seems unlikely that tax increases up to this point would not have net-positive effects (particularly as tobacco smuggling is presumably not as much of a problem in richer countries). Given that even an increase in cost of even half the amount mentioned above would likely save almost 10,000 lives over the next 20 years (undiscounted), an increase in the excise tax for tobacco may hence be highly cost-effective in reducing Alzheimer’s morbidity and mortality, all the more so if it is at a negligible or net-negative cost. Notably, an increase in excise tax, according to a tax escalator which outpaces inflation is one of the policies which ASH continue to advocate (see Section 4.4).

Another extremely cost-effective policy for reducing tobacco use, also advocated by ASH, is for increased funding of anti-smoking mass media campaigns. These are currently quite neglected, receiving only £5.86 million in public funding per year171 and, although they can vary in efficacy due to many design and implementation factors,172 can improve general health at a cost of only £49 per additional QALY.173 The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) estimates that such campaigns have an estimated cost-effectiveness of £162 per child prevented from taking up smoking.174175176177 This equates to a cost of roughly £17,670 - £32,730 per case of dementia averted each year (£883 - £1,636 over 20 years, undiscounted), and of £306,800 - £568,100 per death due to dementia averted (£15,300 - £28,400 over 20 years, undiscounted). This still does not compare favourably to some of the most cost-effective charities, but it is still more cost-effective than a great many other dementia interventions, as there is not currently any effective means of treatment and reduction in smoking prevalence is still the most straightforward means of prevention.

NICE has also recommended smoking cessation interventions which are not much less cost-effective than childhood prevention campaigns (£49 per QALY) for overall health, such as programmes which improve access to smoking cessation services (£136-£195 per QALY),178179180181 client-centred cessation services (£50 per QALY),182 programmes to identify and reach populations in deprived areas (£460-£510 per QALY),183184185 drop-in community cessation schemes (£50 per QALY),186 and various others. Overall, we are confident that there are a variety of health interventions in this area which can reduce smoking prevalence with high cost-effectiveness.

Positive wider impacts

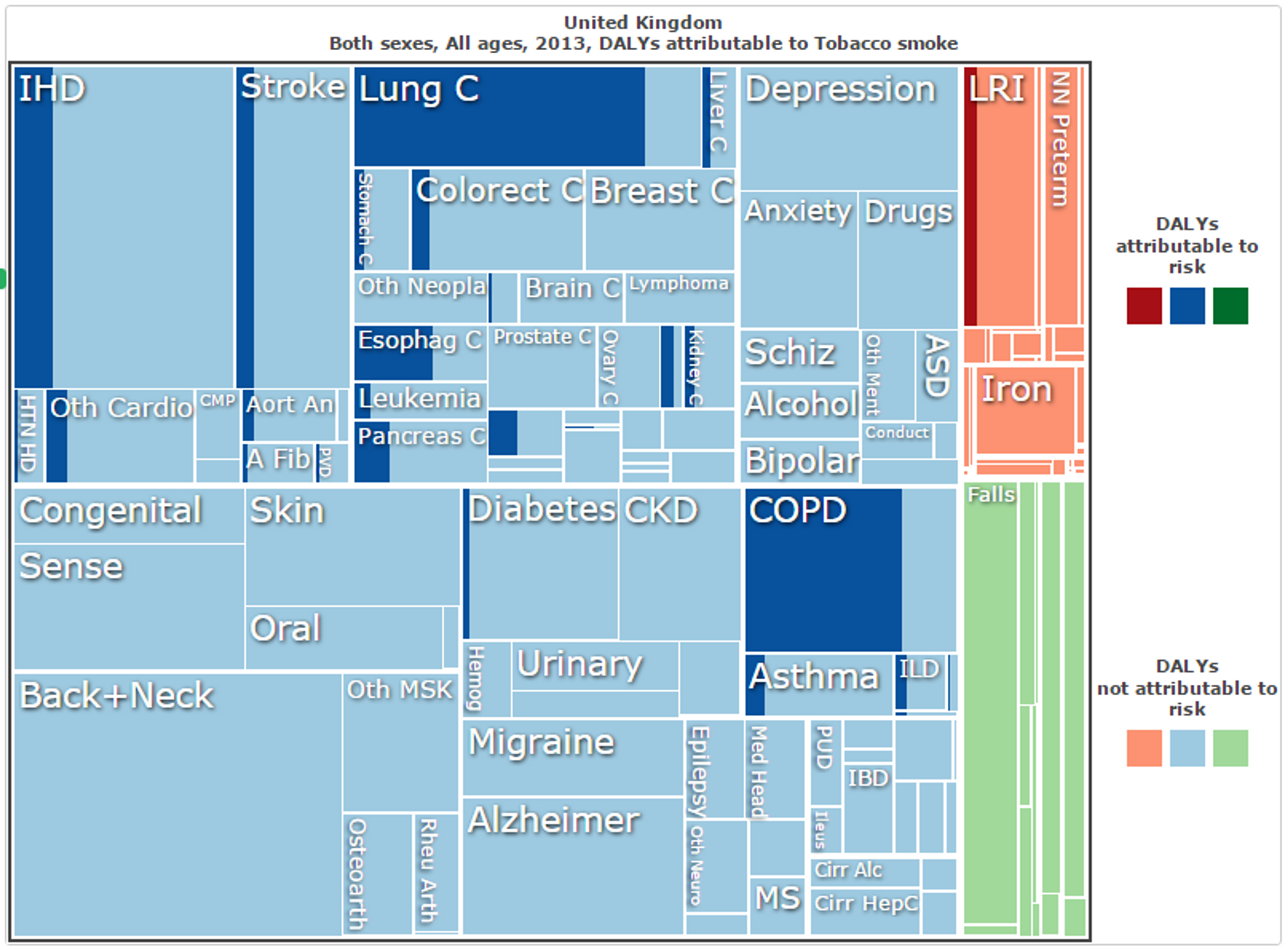

Alzheimer’s disease makes up only a small fraction of the total disease burden attributable to tobacco smoke. Exposure to tobacco smoke has long been confirmed as a major risk factor for various forms of cancer (particularly lung cancer),187 heart disease,188 lung disease,189 stroke,190 aneurysm,191 diabetes,192 asthma,193 and lower respiratory infections (see Figure 6).194195 Despite the fact that only 19% of the population are smokers,196 it is estimated that smoking causes more than 78,000 deaths in England each year.197 This includes 36,800 cancer deaths, 23,800 deaths due to respiratory diseases, 900 due to digestive diseases, and 16,700 due to diseases related to the circulatory system.198 With reductions in smoking prevalence expected to lead to reductions in all of these disease burdens,199 it is therefore fairly certain that tobacco control will have benefits much greater than just the reduction in Alzheimer’s prevalence.

_Figure 6: Proportion of DALYs attributable to tobacco smoke in the United Kingdom each year, excluding those due to dementia, represented by the shaded areas.200

For tax increases, for instance, it is estimated that for every 10% increase in cost there will be a 4% drop in consumption.201 From this, it can be very roughly estimated that a 10% increase in cost would save 3,100 lives per year that it is in effect in the UK (in addition to 790 for dementia) - 62,400 over the first 20 years (in addition to 15,800 for dementia). This is for a policy which not only does not cost any sizeable amount of public funds, but in fact brings in revenue which can then be used for other health interventions.

Likewise, other tobacco control strategies such as mass media campaigns also have sizeable co-benefits. It has been found that such campaigns can improve overall health at a rate of £49-91 per QALY, making them one of the single most cost-effective health interventions available.202

While the increased risk of dementia due to smoking is indeed considerable, even without this increased risk, the broader health benefits still provide an extremely compelling case for tobacco control and ensure that awareness and lobbying activities may still be extremely cost-effective from a cause-neutral perspective.

Due diligence: Possible offsetting/negative impacts

Would more funding decrease smoking at the same level of cost-effectiveness?

Tobacco consumption decreases by 4% for every 10% increase in price in HICs such as the UK,203 so if additional funding would achieve higher tax increases over the same time period, it would do even more good. However, it is unclear whether the cost-effectiveness of doing so would remain constant after already achieving several tax increases - does achieving a 20% increase in price costs twice as much as achieving a 10% increase within the same time period, or does it cost half or 4 times or 10 times as much? Advocacy work is particularly vulnerable to this uncertainty - is there a point of diminishing returns, or perhaps some level of taxation beyond which a serious public backlash might occur? These are extremely difficult questions and the answers are unclear. This introduces considerable uncertainty into our estimates of cost-effectiveness, although it is fairly certain that additional work on tobacco control will continue to have net-positive impacts.

Are the benefits too far in the future? (If discounted with time, are they still greater than for other interventions?)

Whether to discount lives saved (or DALYs averted) with time is a controversial moral question. Note that tobacco control as a health intervention in particular, any cost-effectiveness estimates might be substantially higher once they are time discounted. This means that because the positive health effects from reduced smoking often only occur in many years from the time of the intervention, one may choose to discount their value, and instead prefer other health interventions that have an immediate pay off. This is not only because interventions that have immediate effects might have societal benefits, but also because we might have cost-effective treatment for dementia in the future. In other words, there is an opportunity cost involved in donating money to a cause now when the same donation could instead be made later and still have the same effect at the same time - however, this does not seem to be a significant factor for donations to anti-tobacco lobbying as the actions which are taken to improve health, and for which donations are required, are taken within a year or two and hence discounting is not a major problem in this sense.

More problematic is the cost of having health improvements occur later rather than at present, which results in the flow-on effects of better health only beginning sometime in the distant future. We have not considered such flow-on effects in our analysis of tobacco control and Alzheimer’s disease, but it remains the case that the consideration of such effects may result in other interventions being found to be more cost-effective. This is particularly due to Alzheimer’s disease taking approximately 20 years to develop (see Section 1), the potential delay between price changes (and other tobacco control measures) and individuals quitting smoking, and the delay between lobbying efforts and legislative changes. In total, this may potentially delay the health benefits (for Alzheimer’s specifically) by perhaps 30 years. At a 3% annual discount rate (as is often used by economists), this reduces the effect size by 69% and increases the cost per case, death and DALY averted by 142% (for instance, for ASH, from £531,800-£985,000 per one life saved per year to £755,200-£1,399,000). This is quite concerning, as the effects may be discounted to less than half of what we estimated above.

One possible objection to this level of discounting would be that there was a relatively short time before follow-up used in the studies which demonstrate the link between smoking and dementia. This is true - although the follow-up time varied in these studies from 1 year to 47 years, the majority were less than 10 years.204205206 However, there is likely a very strong correlation for individuals between smoking at present and smoking in previous years so, although the follow-up time may be less than 10 years, the tobacco use which is relevant to whether an individual had developed dementia at the time of follow-up may still have occurred 20 years beforehand. Given this, it remains plausible that the benefits of reducing Alzheimer’s prevalence may still occur several decades after individuals initially quit smoking.

Despite this, the continuing benefits over time still appear to outweigh the discount rate. Even if the benefits of lobbying do not occur until 30 years afterwards, the accrued benefits over the following 20 years still add to 629% of the initial per-year effect size (or 971% over 40 years) - for example, this reduces the cost per life saved after a 30 year delay from £755,200-£1,399,000 per life per year to £120,100-£222,500 per life over 50 years.207 With a lower discount rate of 1% or 2% as is occasionally used for some purposes, this effect size is even larger (and closer to . Thus, we do not believe that discounting is likely to reduce the cost-effectiveness of tobacco control for reducing Alzheimer’s prevalence by a great deal.

Also, tobacco control remains highly cost-effective in improving general health. The figures of less than £100 per additional QALY mentioned above already have discounting accounted for. Thus, we are still confident that tobacco control is highly cost-effective in reducing overall morbidity and mortality, with or without discounting.

4.3 Neglectedness

We have previously investigated the neglectedness of tobacco control and awareness raising in developing countries,208 but it is less clear whether it is as neglected in developed countries such as the UK. However, given that tobacco control in the UK is currently lower (in proportion to disease burden) than for other health initiatives, that funding for awareness campaigns is far less than is spent on pro-tobacco advertising, and that funding for anti-tobacco lobbying remains far less than for pro-tobacco lobbying, we can conclude that it does remain a sufficiently neglected cause area.

Firstly, current funding for smoking cessation is relatively low. The NHS spends roughly £88 million each year on its Stop Smoking Services,209 HMRC spends approximately £90.7 million on combating tobacco smuggling,210 public funding for anti-smoking mass media campaigns in England and Wales is only £5.86 million per year (despite this being one of the single most cost-effective health interventions available, at £49 per QALY gained),211212 and there are also minor expenditures on the efforts of local authorities to combat smoking,213 on the National Centre for Smoking Cessation and Training,214 and on anti-smuggling media campaigns.215 Including the unknown costs of policing tobacco sales, this equates to little more than £200 million per year on tobacco control, which is responsible for more than 11% of the total disease burden in the UK (in DALYs).216 In comparison, all forms of cancer combined make up 17% of the disease burden,217 yet £5 billion is spent each year by the NHS on cancer treatment.218219 Even more disproportionately, mental health and and neurological disorders constitute 18% of national disease burden,220 yet more than £11 billion is spent each year on their treatment.221 Given this sizeable disparity, prevention of deaths due to tobacco appears to be relatively neglected and it is quite likely that a redistribution of funds could potentially reduce the overall burden of disease significantly.

Expenditure on anti-smoking awareness campaigns is also relatively low. Public funding, the primary source of funding for these campaigns, provides only £5.86 million per year.222 In comparison, before tobacco advertising and sponsorship was outlawed, £25 million was spent each year by tobacco companies on advertising in the UK.223 In addition, more than £10 million is currently spent on e-cigarette advertising each year.224225 Given that £25 million could be used productively to increase tobacco use, it seems plausible that a comparable amount could be used productively to decrease it (particularly as tobacco use is still at 18.4% in the UK, compared to 26% in 2002).226227

For political advocacy in particular, the lobbying against tobacco appears to be severely underfunded. ASH, seemingly the most prominent single organisation in this area,228 spent only £723,000 in 2015 on all of its activities, of which lobbying is only a small percentage.229 To compare to corporate pro-tobacco lobbying is quite difficult, as there is little information about lobbying spending made available to the public. Nonetheless, tobacco sales in the UK totaled more than £18 billion in 2013, and annual industry profits are estimated to be in the range of £1.1-1.7 billion in the UK alone.230 In addition, of all companies involved in the practice, Philip Morris International has been ranked as the single biggest spender on lobbying in the European parliament (for which there is information available) with an expenditure of more than £4 million in 2013.231232 Given the sizeable profits made on tobacco products in the UK and the practices of tobacco companies elsewhere (as well as evidence of their lobbying activities in the UK),233234235 it seems that it is extremely unlikely that the funding for anti-smoking lobbying is at all comparable. Thus, it is quite likely that political advocacy against tobacco would continue to benefit from further funding, as a relatively neglected area.

Finally, it appears that ASH is in particular need of donations at present. Recent policy changes at the Department of Health require that grants made to charities such as ASH (which was previously funded largely by government) not be used for any form of political lobbying.236 Given that a large portion of ASH’s activities involve political lobbying, and that £200,000 of ASH’s funding in 2015 came from the Department of Health, this may lead to ASH experiencing a large funding gap in future.

4.4 Charities working in this area

See our full report on Action on Smoking and Health.[^fn-a]: Herttua, Kimmo, Pia Mäkelä, and Pekka Martikainen. "An evaluation of the impact of a large reduction in alcohol prices on alcohol-related and all-cause mortality: time series analysis of a population-based natural experiment." International journal of epidemiology (2009): dyp336.