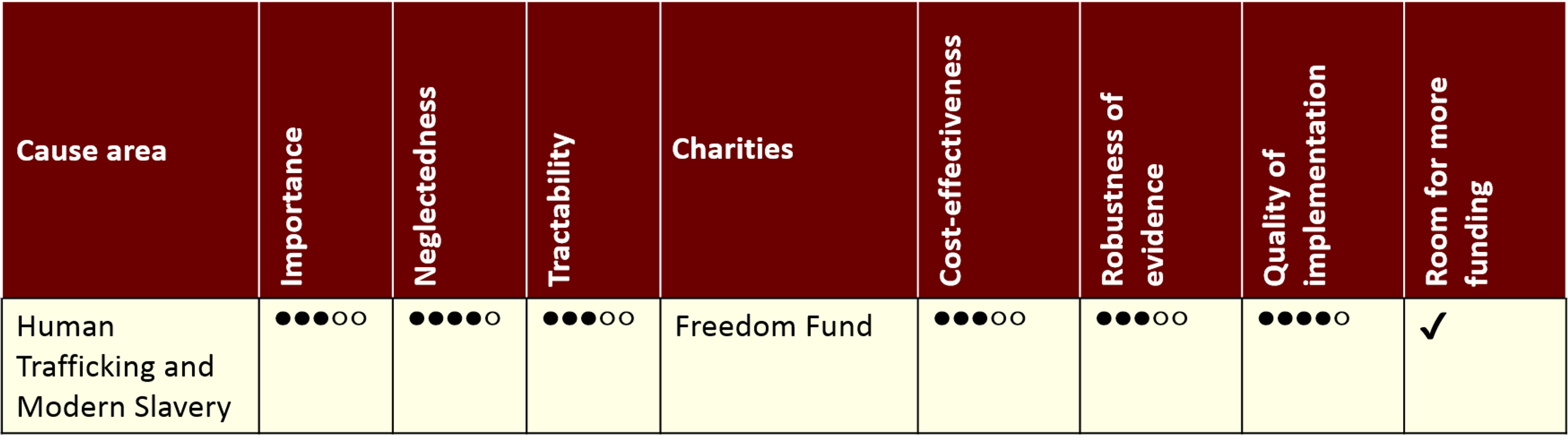

Human Trafficking and Modern Slavery

Giving What We Can no longer conducts our own research into charities and cause areas. Instead, we're relying on the work of organisations including J-PAL, GiveWell, and the Open Philanthropy Project, which are in a better position to provide more comprehensive research coverage.

These research reports represent our thinking as of late 2016, and much of the information will be relevant for making decisions about how to donate as effectively as possible. However we are not updating them and the information may therefore be out of date.

Cause Area: Human trafficking and modern slavery

Human trafficking and modern slavery have been estimated to affect 36 million people worldwide. In this area, the best charity we have identified is the The Freedom Fund, a regranting organisation that coordinates global attempts to eliminate modern slavery through a combination of direct interventions and political advocacy. Regranting and advocacy organisations are particularly hard to evaluate but, at a very high level, it has been estimated that one slave in India has been freed for every US$657 donated.

Importance

How badly does it affect people?

Modern slavery and human trafficking has a substantial toll on psychological, physical health.

Human trafficking causes physical, sexual and psychological harm, and is associated with occupational hazards, legal restrictions and psychological problems as a result of marginalisation and stigmatization[^fn-1].

Reported problems include headache, back pain, significant weight loss, sexual and reproductive health problems, and sexually transmitted infections1. Injuries, malnutrition, rape and infectious diseases (e.g. tuberculosis, hepatitis, malaria and pneumonia) worsen the situation of those trafficked and exploited1.

We believe it is reasonable to think of the human burden of modern slavery analogously to living with a severe disease burden. As such, we have assigned an approximate DALY weight to living in slavery of between 0.3 to 0.7. For comparison, acute low back pain with leg pain has a weight of 0.322, a moderate episode of major depressive disorder has a disability weight of 0.406, and the second most severe illness, severe multiple sclerosis, has a disability weight of 0.7072. While we don’t think that on average, the physical health problems are as severe as those of very severe disease, the physical problems combined with the psychological ones might warrant assigning such a high disability weight.

How many people does it affect?

The 2014 Global Slavery Index estimates that globally there are 35.8 million people who live in modern slavery3, and the International Labour Organisation estimated that there were 21 million victims of forced labour alone4. We have not yet been able to interrogate these numbers fully and so are not fully confident as to the precise conditions of those included (the Global Slavery Index seems to include forced or servile marriage, but it is unclear under which conditions). We are assured that both estimates are at least on the same order of magnitude.

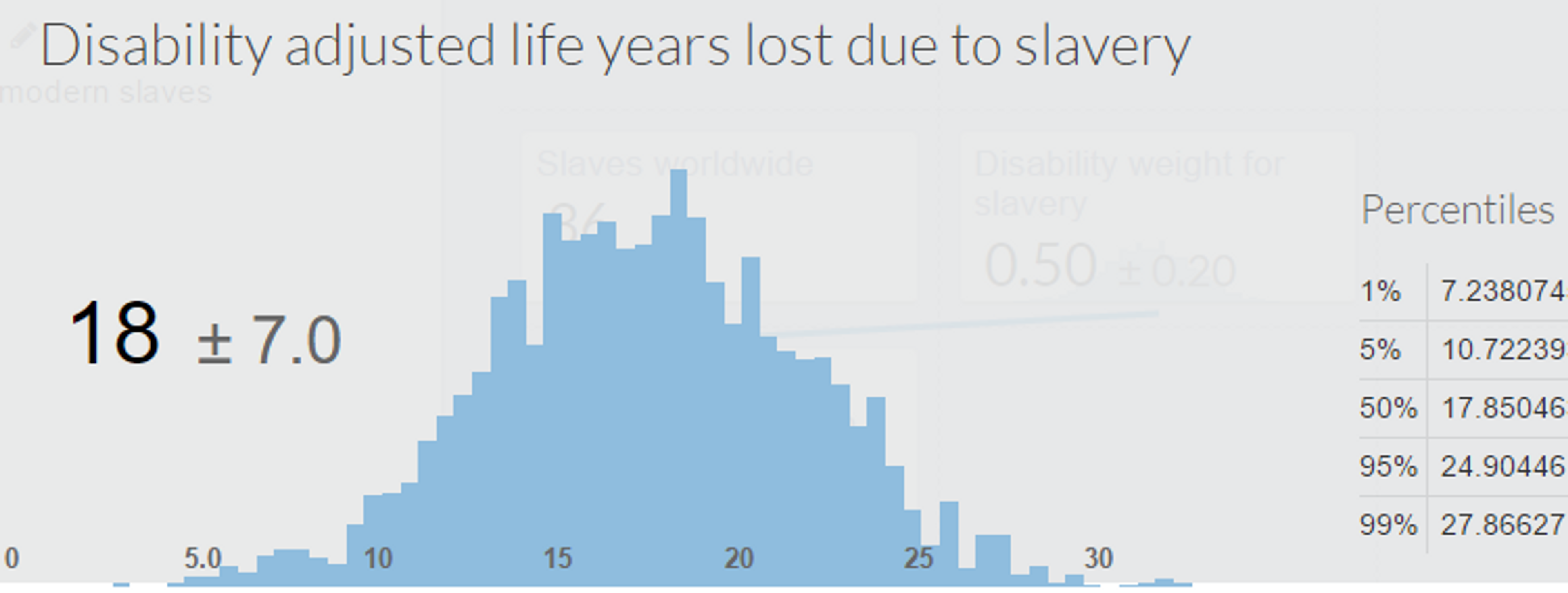

Multiplying these number with the disability weighting from above (0.3-0.7 × 35.8 million) suggests that modern slavery imposes a burden equivalent to 18 ± 7.0 million disability-adjusted life years (see Figure 1). This is comparable to intestinal infectious diseases (about 15 million DALYs), but lower than HIV/AIDS (in 2010 it was about 81.5 million DALYs5), the fifth largest cause of health loss in the world6. This is a surprisingly high result even when considering the lower bound.

Above and beyond the impacts on human wellbeing, slavery is universally considered a human rights violation.

Figure 1: Disability Adjusted Life years lost due to slavery in million: 18 million (± 7.0) disability adjusted life years are incurred due to slavery.

Neglectedness

In general, like many issues that disproportionately affect developing countries, we believe that the issue of modern slavery and trafficking is relatively neglected.

One recent paper7 estimates that donor countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) are spending only a total of about USD 124 million annually to combat modern slavery internationally.

Relative to the estimated disability burden, this seems quite low. This might be partially explained by the fact that slavery does not spread like a disease8, but even taking this into account, slavery seems relatively neglected.

Kevin Bales, who is generally considered an expert on the topic of slavery (three experts that we have contacted cite him as an authority on this subject), estimates that at $400 per freed slave and it would cost about 10.8 billion dollars to free all 27 million slaves (this was an earlier estimate)9 - though he has told us that the cost-effectiveness estimate is outdated and would now be higher. In addition, there is of course substantial uncertainty around these estimates. However, this estimate is roughly comparable to that of the Freedom Fund ($657 to liberate a slave in India - see the Cost-effectiveness section of our Freedom Fund evaluation).

A report by the International Labour Organization estimates that the illegal profits from exploiting forced labour total $150 billion each year. One paper comments that “A simplistic sum—dividing these profits [150 billion] by the amount invested in stopping human trafficking [124 million] might suggest that not enough is being spent.“4. We return to this point in the following section.

In 2013, the Freedom Fund was founded by three billionaires10 (with a combined wealth of about $11 billion), who each invested only 10 million dollars each in order to to raise an additional $70 million for smart anti-slavery investments by 2020.

Tractability

All countries, except North Korea, have domestic legislation which criminalises some form of modern slavery11. This suggests that there are few strong cultural or political barriers to combating slavery. Moreover, the cost-effectiveness estimates of fewer than $1000 per person liberated (see the Cost-effectiveness section of our evaluation of the Freedom Fund), suggest that this is a tractable intervention.

However, a report by the International Labour Organization12 estimated that the illegal profits from exploiting forced labour are about $150 billion each year, indicating that combating slavery is working against ‘business interests’. In other words, because slavery is profitable, slavers might use their resources to prevent slaves from being freed. In this sense it is less tractable than global health interventions such as preventing malaria, where other actors are not actively working against it.

For further information, see our full evaluation of the Freedom Fund.

- *[^fn-1]: Zimmerman, Cathy, Mazeda Hossain, and Charlotte Watts. "Human trafficking and health: A conceptual model to inform policy, intervention and research." Social Science & Medicine 73.2 (2011): 327-335.