Is tobacco control a "best-buy" for the developing world?

William Savedoff and Albert Alwang recently identified taxes on tobacco as, “the single most cost-effective way to save lives in developing countries” (2015, p.1). This is a strong claim and one that should pique the interest of any effective altruist. Is the claim true? And, if so, does tobacco taxation present an opportunity to do the most good? In this post, I examine whether tobacco tax advocacy gives other highly effective interventions a run for their money. However, this post will not evaluate or recommend a particular charity. My aim is rather to assess whether tobacco tax advocacy is a cause that effective altruists and EA organizations should investigate further and, if so, where further investigation is needed.

Tobacco control and tobacco taxation

The WHO assesses global progress on tobacco control in terms of a set of measures called MPOWER.

- Monitoring tobacco use and prevention policies

- Protecting people from tobacco smoke

- Offering help to quit tobacco use

- Warning about the dangers of tobacco use

- Enforcing bans on tobacco advertising, promotion, and sponsorship

- Raising tobacco taxes

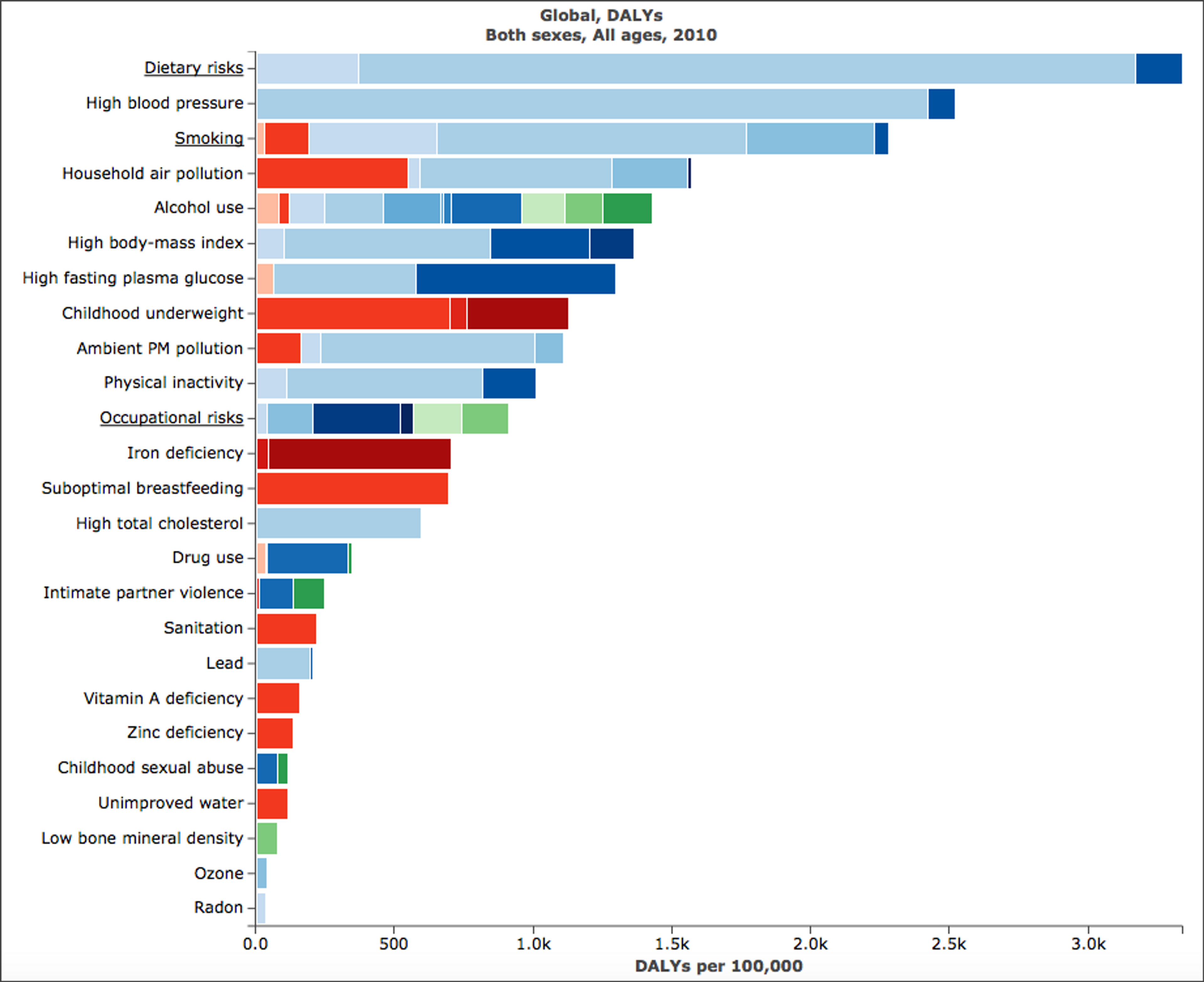

Tobacco control programs often pursue many of these aims at once. However, raising taxes appears to be particularly cost-effective — e.g., raising taxes costs $3 - $70 per DALY avoided(Savedoff and Alwang, p.5; Ranson et al. 2002, p.311) — so I will focus solely on taxes. I will also focus only on low and middle income countries (LMICs) because that is where the problem is worst and where taxes can do the most good most cost-effectively.

None of this is to say, of course, that we should not pursue other tobacco control measures.They are well-studied and effective life-saving interventions. In fact, there is some evidence that advertising bans and public smoking bans can be highly cost-effective (Lai et al. 2007 and Donaldson et al. 2011).

How effective is tobacco taxation as a public health intervention?

It’s clear that smoking is a health risk. As Savedoff and Alwang note, non-smokers live 10 years longer on average than smokers (Jha et al. 2013, p.347); smoking can kill up to two thirds of smokers (Banks et al. 2013); and smoking greatly increases the likelihood of coronary heart disease (2-4x), stroke (2-4x), and lung cancer (25x) (CDC 2014). ( A recent study of US smokers found that 17% of deaths attributable to smoking were caused by diseases not previously linked to smoking (Carter et al., 2015). The implication of this finding is that we may have been significantly underestimated smoking deaths.) The WHO estimates that in the 20th century 100 million people died as a result of cigarette smoking (Jha 2012, p.469).

What does this mean for the future? If current trends in population growth and tobacco use continue, smoking will cause 1 billion deaths in the 21st century, the vast majority of which will be in the developing world (Savedoff and Alwang, p.3; Jha 2012 p.570).

But current trends need not continue. We can prevent deaths from tobacco use. Tobacco taxation is a well-tested and effective means of decreasing the prevalence of smoking—it gets people to stop and prevents others from starting. The reason is that smokers are responsive to price increases,provided that the real price goes up enough. According to one estimate, preventing smoking deaths by raising the real price of cigarettes by 10% costs $3 - $70 per DALY (Ranson et al., p. 315). Another estimate puts the cost of saving a life by diminishing tobacco use at $1462 (5.5millions lives saved over 10 years at an annual cost of $804 million dollars). If 1/3 of the lives saved are due to price increases from higher taxes, which probably underestimates the relative impact of this measure, then the cost of saving a life by raising taxes is about $795 (1.8 million lives saved over 10 years at an annual cost of $143 million) (Asaria et al., 2007, pp.2047-8 and Web table 7).

Even if these numbers are off by a factor of 2 or 3, tobacco taxation appears to be on par with the most effective interventions identified by GiveWell and Giving What We Can. For example, GiveWell estimates that AMF can prevent a death for $3340 by providing bed nets to prevent malaria and estimates the cost of schistosomiasis deworming at $29 - $71 per DALY.

At first glance, then, tobacco taxation seems like an obvious choice for those looking for cost-effective public health interventions. But does its initial attractiveness stand up to scrutiny?

There are a few reasons to balk at recommending tobacco tax advocacy to those aiming to do the most good with their donations, time, and careers.

- Tobacco taxes may not be a tractable issue

- Tobacco taxes may be a “crowded” cause area

- Unanswered questions about the empirical basis of cost-effectiveness estimates

- There may not be a charity to donate to

Spoiler alert! I don’t have a charity to recommend. If, at the end of this post, you’re convinced by the cost-effectiveness of tobacco tax advocacy, there won’t be a donation link for you to click. However, I will have a few things to say about how effective altruists might make a difference in this area.

Importance, tractability, and neglectedness

Even if tobacco taxes are as cost-effective as their proponents suggest, and even if there were a charity capable of effectively advocating for tobacco taxes, we might still have reason not to support or recommend it. When deciding whether to support a particular cause, we typically assess the proposed project along three dimensions: importance, tractability, and neglectedness (or crowdedness).

Is tobacco taxation important?

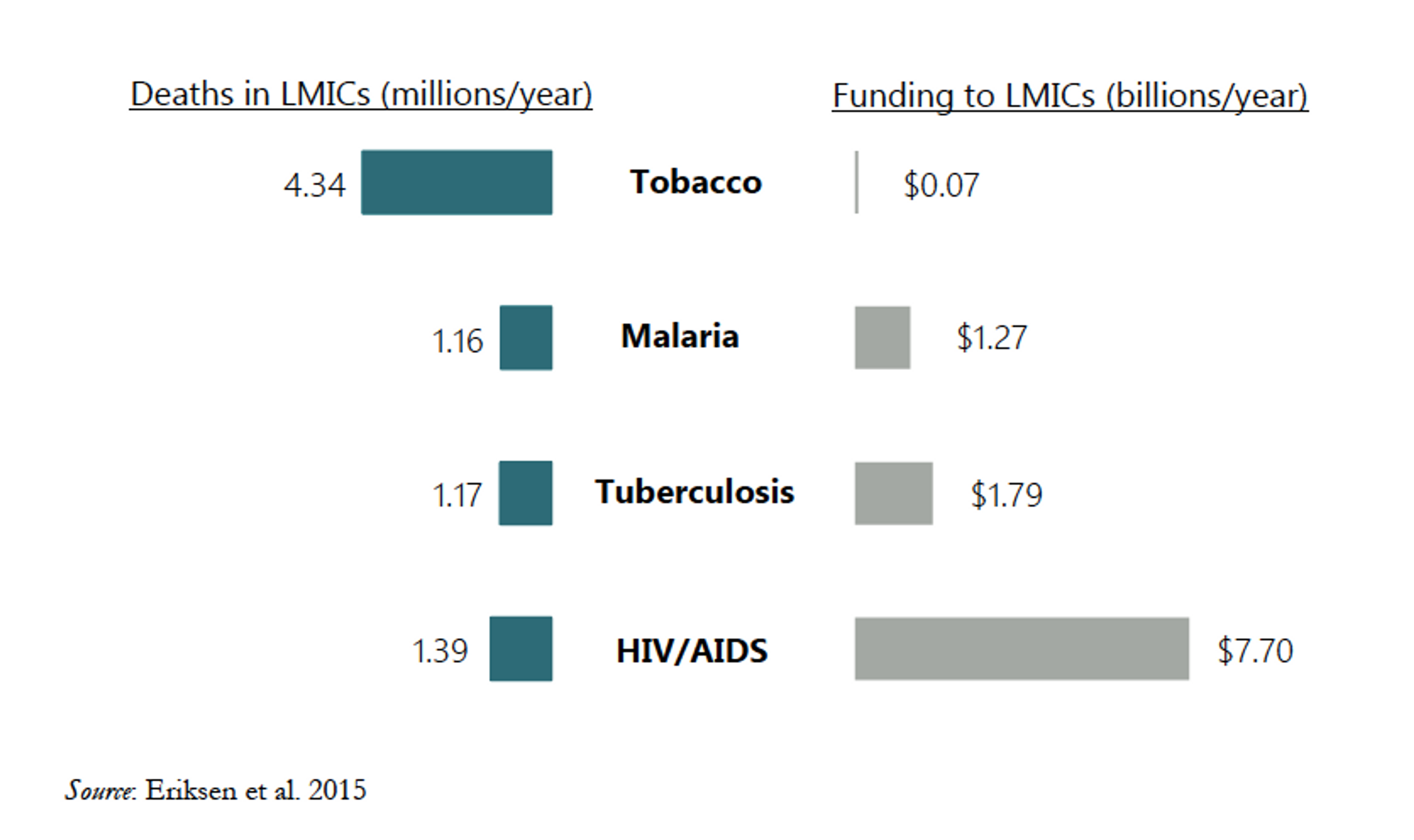

Yes, definitely. Smoking is very harmful and very common. Globally, 21% of people over 15 smoke (WHO GHO). In the developing world, it causes more deaths each year than malaria, tuberculosis, and HIV/AIDS combined (Savedoff and Alwang, p. 4). Preventing even a fraction of the deaths, disease, health costs, and other economic losses caused by smoking would be an enormous benefit. Tobacco control, especially tax increases, could prevent at least 110 million smoking deaths in the next few decades ( Jha 2012, p.591). By comparison the eradication of small pox, one of the most effective public health interventions in human history, has saved upwards of 50 million lives since the campaign concluded 35 years ago. Well-designed and well-managed tobacco taxes have been shown to decrease smoking, and, once established, tobacco tax revenue can be used to support further tobacco control measures or other public health programs.

Is tobacco taxation a tractable intervention?

This question is more difficult to assess, but the available evidence is promising. Many rich countries and various US states have substantially reduced smoking prevalence through taxation. This took quite a while in some places—30years in the US and UK—but was much faster in others. For example, France cut its smoking rate in half between 1990 and 2005 by using tax to steadily increase the real price of cigarettes. And South Africa, a middle-income country, was able to do the same over a similar period (Jha and Peto 2014, pp.64-65).

However, there is one powerful reason to think tobacco taxation might not be a tractable intervention. The tobacco industry and its agents directly and indirectly oppose tobacco control measures, including taxation. They lobby governments, spread misinformation, and bring costly lawsuits against governments that attempt to control tobacco use (see e.g., Mamudu et al. 2008 and Sebrie at al. 2006 ). And other organizations do the same on their behalf. As a result, organizations that advocate for tobacco taxes not only have to design and build support for effective tobacco taxes, but also help defend the policies against the tobacco industry’s attempts to block, dismantle, and neuter them. In addition to this kind of direct opposition, tax advocates may find themselves operating in places where the institutions needed to establish and maintain the tax system are weak, dysfunctional, or corrupt. Such factors and others may explain the (relative) absence of “global level policy prescriptions” and the “lack of public involvement in tax-related policies” noted by Uwe Gneiting (2015, pp.9-10). Finally, some countries may be parties to international agreements that, in practice, limit their ability to defend the legality of tobacco taxes even when these taxes are morally and politically justified.

Nonetheless, even if we acknowledge these obstacles, there are many reasons to be optimistic about the tractability of tobacco tax advocacy.

- There are many venues within which to advocate tobacco taxation. Advocacy efforts can focus on city, state, or national governments. And researchers have identified 23LMICs that together account for 80% of the world’s chronic disease burden, in which to pursue tobacco control measures (Asaria et al.).

- Tobacco control is an active cause area in which opposition and obstacles are being overcome.

- In most countries a majority of people support increased taxes, especially when some of the revenue is used to improve domestic health programs ( WHO Report, pp.30-31) .

- There is an existing tool—excise taxes that sufficiently raise the real price of cigarettes— that can be applied and that is is known to work. In fact, almost all LMICs—121 of 132,for which we have data—already levy excise taxes on tobacco. The problem is that very few levy sufficiently high taxes—i.e., taxes that constitute 45-75% of the retail pack price(WHO Report, pp.78-79).

- The political context—increasing taxes and reforming tax systems to make them more effective—is amenable to incremental change, e.g., 106 countries increased their excise taxes between 2012 and 2014 (WHO Report, p.79), including this recent tax increase in Ghana .

- We have data on the strength of target countries’ tax and regulations systems and tobacco control infrastructure that can allow organizations to target governments most likely to pass and enforce effective taxes (Asaria et al., Webtable 3).

- Large donors are currently funding tobacco tax advocacy in 112 countries and their successes and failures can inform future advocacy (Gates and Bloomberg).

- Successes in places like the Philippines, in the face of tobacco industry opposition, suggest that well-funded advocacy can work, though rigorous evaluation of the cost and cost-effectiveness of these efforts is still needed.

Tobacco tax might seem like an intractable issue, but this concern is not borne out by the evidence.

Is tobacco taxation a neglected cause?

This question is difficult to answer, but my sense is that it is neglected. As I said above, tobacco control is underfunded relative to the harm it causes (Eriksen et al., pp.76-77; use the Savedoff chart on relative funding). HIV/AIDs prevention and treatment received 10 times more funding in LMICs than tobacco control despite the fact that tobacco causes 3 times more deaths in those countries. (Of course without that funding the number of HIV/AIDS deaths would have been much higher, but proponents of tobacco taxes are not suggesting that we divert funding from AIDS to tax advocacy. They are arguing that we ought to fund tobacco control in order to save lives.) The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Bloomberg Philanthropies have recently begun to fund tobacco control at a higher level ($600 million since 2007). And, given the extent of this funding, one might reasonably suggest that tobacco control is not a neglected cause. If it remains cost-effective to increase funding, Gates and Bloomberg will do it. If this is true, then our money would be better spent elsewhere.

However, I am not persuaded that tobacco control is as crowded as these critics suggest. Even accounting for Gates’ and Bloomberg’s contributions, tobacco control is underfunded relative to the harms caused by smoking. Nor is there much evidence to suggest that there is not room for more funding. Hana Ross and Michal Stoklosa consider the possibility that Gates and Bloomberg might be “crowding out” other Development Assistance for Tobacco Control (DACT). After 2006, when Bloomberg and Gates committed to funding tobacco control, some other organizations reduced or ended their funding. However, this drop in funding might be due instead to the effects of the global financial crisis (Ross and Stoklosa 2012, pp.468-469). More evidence is needed to establish both the effects of the financial crisis on DACT and the effects of these large donors on both DACT and domestic funding for tobacco control.

The academic research seems to suggest that spending more would be highly cost-effective. Gates and Bloomberg have contributed $600 million since 2007. This represents about half of total DACT (Ross and Stoklosa, p.466). However, one estimate of the amount needed for the four “best buys” in tobacco control, which includes tobacco taxation, is $600 million per year (or $0.11 per capita per year) (Eriksen et al., pp.76-77). Another estimate puts the cost of decreasing smoking prevalence in key LMICs to 5% by 2040 at $6 billion per year. Tobacco control accounts for about 10% of those costs, or $600 million per year (Beaglehole et al. 2011, pp.1440 and 1444). Finally, if we think that the estimated costs for advocacy are too low, then these numbers will be even higher.

At the very least, these numbers suggest that the amounts of money currently moved by GiveWell ($27 million as of April 2015), which includes the amount moved by Giving What We Can ( $7 million over 5 years), could all be used effectively for tobacco tax advocacy.

Questions about cost-effectiveness

Should we be satisfied with the cost-effectiveness numbers cited by Savedoff and Alwang and others? Perhaps, but effective altruists interested in supporting tobacco tax advocacy, or tobacco control more generally, should consider the following questions.

Would more funding allow us to decrease smoking prevalence more quickly at the same level of cost-effectiveness?

Tobacco consumption decreases by 4% for every 10% increase in price (Savedoff and Alwang, p.4), so if additional funding would achieve higher tax increases over the same time period, it would do even more good. However, we want to know not only whether additional funding will do more good, but also whether cost-effectiveness will change? Does achieving a 20% increase in price costs twice as much as achieving a 10% increase within the same time period? Or does it cost half or 4 times or 10 times as much? We need to know the answer to this question.

How would cost-effectiveness estimates change if we assumed that some proportion of tobacco tax revenues would be used for tobacco control or other highly cost-effective public health programs?

Currently, LMIC governments collect $10.74 per capita in revenue from excise taxes on tobacco products, but spend only $0.0078 per capita on tobacco control—DACT provides another $0.011 per capita. This may well be justified. Directing just 1% more of these revenues (or $0.1074 per capita) to tobacco control would increase total spending on tobacco control by more than 500% (Eriksen et al., pp.76-77). Increasing funding in this way may diminish or even eliminate the need for additional DACT, including charitable donations, in the long term. But designing policies that directly fund domestic tobacco control or other cost-effective public health interventions could substantially improve the overall cost-effectiveness of tobacco taxes in the short term, while strengthening domestic public health services.

How would cost-effectiveness estimates change if we discount future lives in the way some economists and philosophers suggest?

First of all, time discounting is a controversial moral question. Second, at least one of the estimates given above discounts projected future DALYs at the standard 3% rate (Ranson et al., p.314). Moreover, even if we accept such a discount rate, increasing tobacco taxes has both short term benefits (for those who quit smoking) and long term benefits (both for those who quit smoking and those who never start (Jha and Peto, pp.63-64). Indeed, Asaria et al. estimated that 5.5 million lives could be saved in the next decade (this estimate was for the period from 2006-2015).

Are the proposed tobacco taxes regressive—i.e., does their burden fall primarily on the poor?

This is an important question and a natural one to ask given that we’re proposing taxes in LMICs on a product used mostly by the poor. However, the evidence strongly suggests that the tax is not regressive. Savedoff and Alwang point out that while poor people smoke more thanaffluent people, they are also more sensitive to price increases. This means they are more likely to smoke less or quit in response to price increases. As a result, most of the health benefits of tobacco taxes will accrue to low-income individuals, while most of the tax burden will be born by richer smokers who continue to smoke even when the price has increased (Savedoff and Alwang, pp.8-9, Jha et al., 2012, p.8 ).

Do current estimates accurately assess the cost and cost-effectiveness of advocacy for tobacco taxation?

This is the crucial question for effective altruists interested in donating to tobacco tax advocacy. Organizations funding tobacco control pay for political advocacy, institutional support, and research and they advocate for tobacco taxes by lobbying and advising politicians and civil servants. Thus it is crucial that we have an accurate estimate of the cost of personnel and material resources necessary to complete a successful campaign. However, it is often difficult to measure the effectiveness of political advocacy ( Teles and Schmitt 2011 ), specifically whether and to what degree the campaign made the difference. And, even when we can measure its effectiveness, we may not be justified in generalizing from one context to another—e.g., a successful campaign in Thailand might not be successful or might cost much more in Nigeria. However, rather than generalize, researchers calculate program costs based on general WHO estimates and the strength of a country’s tax and regulation systems and then total the costs for each country (Johns et al. 2003, Asaria et al., Webtables 3 and 7).Nonetheless, if we were to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of a particular organization, we would quite reasonably ask for more concrete numbers based on actual past campaigns. This seems particularly important given that tobacco tax advocacy is likely to experience direct opposition from tobacco industry agents (Ranson et al., p.314). And it seems reasonable now that large,outcome-focused donors have funded a number of successful campaigns.

What can you do with this information?

At the beginning of this post, I asked whether tobacco taxes can really claim to be one of the most—or even the most—cost-effective way of saving lives in the developing world. I think we have good reason to think they are, though we should ask for answers to the above questions—or at least better answers than I’ve been able to give.

I also asked whether tobacco tax advocacy provides an opportunity to do the most good with our time, careers, and charitable donations. Unfortunately, with regard to donating, the answer seems to be no—at least for now. The Gates Foundation and Bloomberg Philanthropies currently provide almost all the charitable funding for tobacco control. It is not possible to donate to Bloomberg Philanthropies. You can donate to the Gates Foundation, but cannot direct your donation to tobacco control. You can donate to some of the tobacco control organizations that these large donors support, e.g., the Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids, but robust evidence of the effectiveness of these organizations’ particular advocacy efforts is currently unavailable. Tobacco taxation may indeed be the most cost-effective way to save lives in the developing world, but it’s not a good option for individual donors at this time.

But donating to a charity is only one way to do good. So what, if anything, can you do with the information I’ve provided? I think the evidence warrants further attention to tobacco taxes and there are a few ways in which a person may be able to do a lot of good.

Investigate and evaluate the effectiveness of actual tobacco tax campaigns. Bloomberg and Gates both fund organizations that advocate for tobacco taxes as part of their tobacco control missions (check out the Gates grantees and Bloomberg grantees) and Bloomberg identifies 52 countries where they work that have passed tobacco control legislation. For example, they fund organizations like the Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids, who have pursued tax advocacy at the state level in India, Action for Economic Reforms, who were involved in the Philippines’ “sin tax” reforms, the Southeast Asia Tobacco Control Alliance, and other organizations that advocate for tobacco control. I think the time is right for Giving What We Can and GiveWell to do this kind of research.

Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids is one place to start. Using easily available information, a quick back of the envelope calculation for CTFK’s Indian state tax campaign—assuming that their estimate of the premature deaths averted is roughly accurate (1,205,241)</>, that their advocacy was responsible for just 5% of that outcome, and that their entire program services budget ( $16 million for 2013) went to the India campaign for 3 full years—suggests a cost of $800 to avert 1 death. This is very promising.

Are you already a convert to the tobacco tax cause? Then work for an effective tobacco control organization. If your time or expertise allows you to make the biggest difference (on the margin) in this area, take advantage of that fact—here are some jobs at CTFK if so.

Or identify an effective research organization working on tobacco control—and with the capacity to expand; and fund an expansion of their work. For example, the Open Philanthropy Project is funding Dr. Michael Clemens’ research on labor mobility at the Center for Global Development.Some areas of tobacco tax research seem particularly important: evaluating the cost-effectiveness of tax advocacy campaigns, identifying which types of tobacco tax to advocate in which contexts, designing policies that use tobacco tax revenue effectively, identifying andr anking suitable venues for future advocacy, and tailoring campaigns for difficult but high value targets like China, which consumes more cigarettes than all other LMICs combined (Eriksen etal., p.31).

Finally, if this post has made tobacco tax advocacy look like a compelling cause, consider investigating other public health measures where what’s needed is political advocacy, rather than direct delivery of goods like deworming pills. Advocacy for policies to control salt intake is one such option (Asaria et al.).

Tobacco taxes appear to be a highly cost-effective way to save lives in the developing world. I suspect that further research will show that well-run tax advocacy organizations can save lives as cheaply as the charities currently touted by organizations like GiveWell and Giving What We Can. For now that research remains to be done, but I want to close by noting one more consideration in favour of tobacco tax advocacy. The effective altruism movement has been criticized for its “narrow view of impact”—e.g., ignoring the kinds of effects that can’t be or aren’t measured by randomized controlled trials. Emily Clough suggests that the effectiveness of a program that, say, delivers bed nets should be assessed, in part, on the degree to which it“unintentionally demobilized political pressures on the government to build a more effective malaria eradication program.” But tobacco tax advocacy does not face this kind of worry. Indeed, its raison d’être is to mobilize citizens, civil servants, and political leaders in pursuit of a home-grown and self-supporting public health program. Whether or not one agrees with criticisms like Clough’s, effective altruists should welcome and encourage greater attention to this sort of cause.

Thanks to Hauke Hillebrandt, William Savedoff, and Scott Weathers for helpful feedback on an earlier draft of this post.

References

Asaria et al. 2007. “Chronic disease prevention: health effects and financial costs of strategies to reduce salt intake and control tobacco use.” The Lancet 370, 2044-53.

Banks et al. 2015. “Tobacco smoking and all-cause mortality in a large Australian cohort study:findings from a mature epidemic with current low smoking prevalence.” BMC Medicine 13, 38.

Beaglehole et al. 2011. “Priority actions for the non-communicable disease crisis.” The Lancet 377, 1437-47.

Carter et al. 2015. “Smoking and Mortality—Beyond Established Causes.” New England Journal of Medicine 372, 631-40.

Donaldson et al. 2011. “A Cost-Effectiveness Analysis of India’s 2008 Prohibition of Smoking inPublic Places in Gujarat.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 8,1271-1286.

Eriksen et al. 2015. The Tobacco Atlas 5th ed. The American Cancer Society.

Gneiting, Uwe. 2015. "From global agenda-setting to domestic implementation: successes and challenges of the global health network on tobacco control." Health Policy and Planning, 1-13.

Jha, Prabhat. 2012. “Avoidable Deaths from Smoking.” Public Health Reviews 33.2, 569-600.

Jha, Prabhat and Frank Chaloupka. 2000. “The economics of global tobacco control.” British Medical Journal 321, 358-61.

Jha et al. 2012. Tobacco Taxes and Health: A Win-Win Measure for Fiscal Space and Health. Manila, Asian Development Bank.

Jha et al. 2013. “21st Century Hazards of Smoking and Benefits of Cessation in the United States.” New England Journal of Medicine 368, 341-50.

Jha, Prabhat and Richard Peto. 2014. “Global Effects of Smoking, of Quitting, and of Taxing Tobacco.” New England Journal of Medicine 370, 60-8.

Johns et al. 2003. “Programme costs in the economic evaluation of health interventions.” Cost Effectiveness and Resource Allocation 1,1.

Lai et al. 2007. “Costs, health effects, and cost-effectiveness of alcohol and tobacco control strategies in Estonia.” Health Policy 84, 75-88.

Mamudu et al. 2008. “Tobacco industry attempts to counter the World Bank report curbing the epidemic an WHO framework convention on tobacco control.” Social Science and Medicine 67.11, 1690-99.

Ranson et al. 2002. “Global and regional estimates of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of price increases and other tobacco control policies.” Nicotine and Tobacco Research 4,311-19.

Ross, Hana and Michal Stoklosa. 2012. “Development assistance for global tobacco control.” Tobacco Control 21, 465-70.

Savedoff, William and Albert Alwang. 2015. “The Single Best Health Policy in the World: Tobacco Taxes.” CGD Policy Paper 062 . Washington DC, Center for Global Development.

Sebrie et al. 2005. “Tobacco industry successfully prevented tobacco control legislation in Argentina.” Tobacco Control 14.5.

Teles, Steven and Mark Schmitt. 2011. “The Elusive Craft of Evaluating Advocacy.” Stanford Social Innovation Review.

WHO. 2003. Making Choices in Health: WHO Guide to Cost-Effectiveness Analysis. Eds. Edejer et al. Geneva, World Health Organization.

WHO. 2015. WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic, 2015: Raising taxes on tobacco. Geneva, World Health Organization.