Improving global health

Each year, millions of people — almost all from low-income countries — die each year of preventable and curable conditions like tuberculosis, malaria, and diarrhoeal disease.

As of 2021, approximately 700 million people — just under 10% of the world's population — live in "extreme poverty," defined as $1.90 per day. These are in “international dollars,” meaning it takes into account that one dollar can go a lot further in some countries than others.1 This means they are severely deprived of basic human needs, including food, water, shelter, healthcare, and education. This has a profound negative impact on their health and wellbeing.

Charities working in global health aim to improve and save the lives of people around the world. The most effective charities reduce suffering by focusing on diseases that are preventable and easily treated, allowing them to impact the maximum number of people.

Why is global health important?

We think global health is a high-priority cause because its scale is so significant and the cost-effectiveness and scalability of interventions in this area indicate that we can make immense progress with further resources. While funding has increased significantly in recent years, this cause is still neglected relative to its scale.

What is the scale of the problem?

As mentioned above, 700 million people live in extreme poverty, defined as living on less than the local equivalent of $1.90 USD per day. The UN estimates that 1.3 billion, or over 20% of the world's population, live in multidimensional poverty. Multidimensional poverty is a more holistic assessment of poverty that looks at a person's healthcare, education, and living standards to determine poverty levels. Although rates of multidimensional poverty have decreased over the last few decades, and people are living longer and healthier lives, a significant portion of the world's population are still multidimensionally poor.

Another concern is that the COVID-19 pandemic — as well as emerging challenges like global conflict, famine, and climate change — threaten to slow down, or even reverse some of this progress. For example, recent research suggests that climate change could pull over 100 million people into extreme poverty.

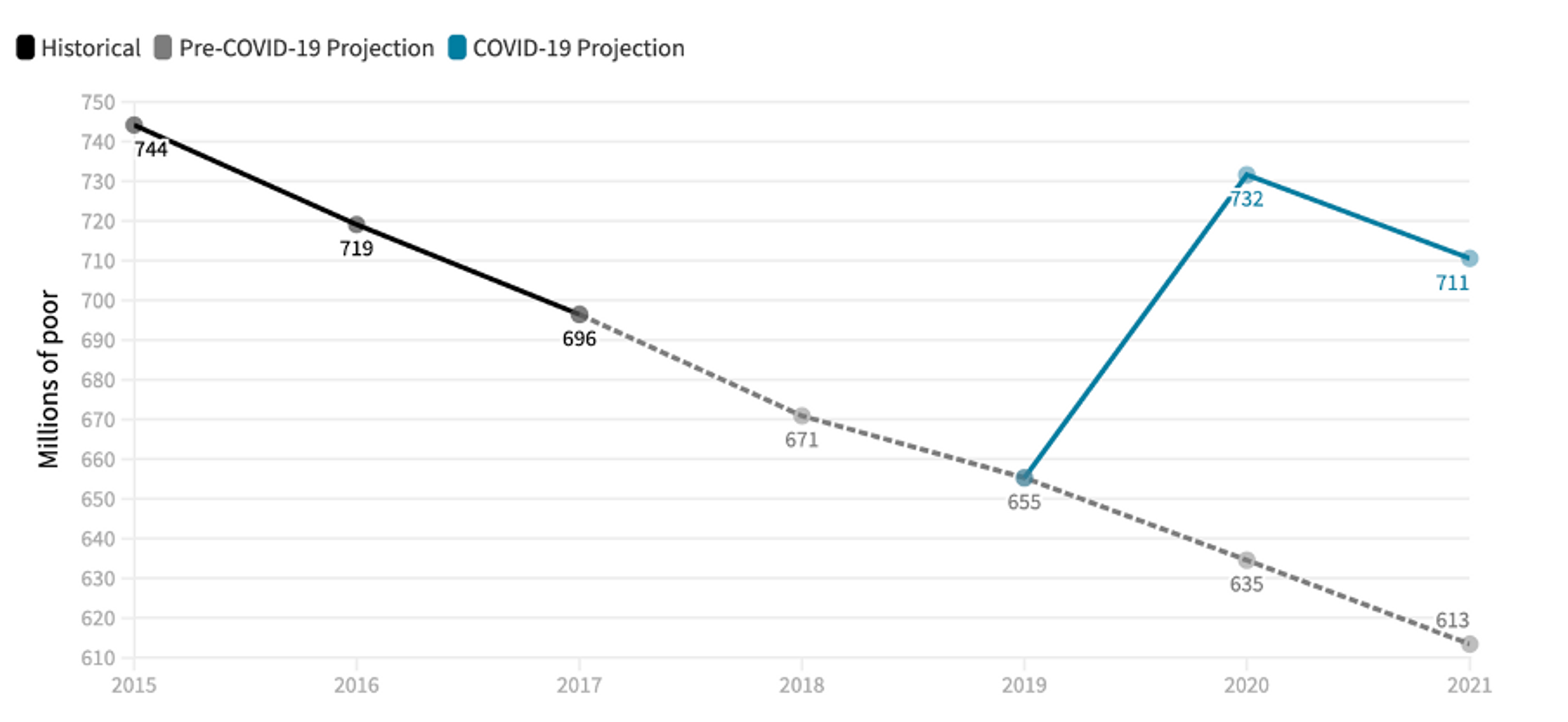

Data from the World Bank shows that the number of people living in extreme poverty is generally decreasing, but in 2020 it rose (for the first time in 20 years). This is likely due to COVID-19.

Is more money needed for global health?

A significant amount of work is being done in global health and development in general, with much of that going to support global health specifically, so global health is less neglected than other high-priority causes. Over $160 billion USD in grants and loans is given each year by wealthy countries to support (and influence) countries in need. Although this is a lot of money, it only represents 0.32% of the combined gross national incomes of these countries, which is less than half the 0.7% commitment target set by the UN. Further, of this amount, only a small fraction is spent on global health.

There is an enormous amount of work yet to be done, and therefore there is still a strong need for more funding. The US Agency for International Development estimates that we need to triple our global health funding to achieve the UN's health and wellbeing Sustainable Development Goals. Many global health charities doing impactful work have a current funding gap and the capacity to effectively use more money.2

If funding for global health were to drop, current levels of progress may stagnate or even reverse. For instance, according to WHO projections, even moderate disruptions in the access to malaria preventative measures and treatments could lead to over 46,000 additional deaths from the disease per year. As a result, we cannot afford to be complacent about the amount of money donated to global health.

Therefore, relative to the scale of the problem — and even with the increased levels of funding — we think that global health is a neglected cause area.

Does my money reach those who need it?

A common concern is that charitable donations may be wasted, and that only a fraction of money donated to charities reach those in need. And it's true that there is significant variation in how much good different charities within global health achieve: while some charities may have a profound impact, others may do little, or no good. Therefore, if you are considering donating to a charity within global health, it's helpful to think about how you can donate effectively.

Certain charities in global health have a proven record of doing incredible amounts of good through evidence-based and cost-effective interventions. These impactful charities tend to focus on diseases that affect a large number of people, and implement established and effective interventions such as bed nets to prevent malaria. For example, if you donate to Against Malaria Foundation (AMF), you can be reasonably confident that for each $5 USD you donate, you will distribute one insecticide-treated bed net that will prevent at-risk people from contracting malaria. From this, GiveWell estimates that you can save a life for between $3,000–5,000 USD.

The benefit of charities in global health can be measured through cost-effectiveness analyses, which attempt to measure how much good can be done with a given amount of money. From this, we can estimate how much it costs to gain a unit of a health outcome, such as an extra year of life or a life saved.

When possible, these analyses often use the results of randomised controlled trials (RCTs). RCTs provide high-quality and unbiased estimates of the impact of a treatment. They involve getting a select group of people and randomly giving half of them a promising treatment (such as a supplement for Vitamin A). The other half are given no treatment, a placebo, or the standard treatment. We can then measure the difference in outcomes between the two groups. Any improvements as a result of the promising treatment are often expressed in lives saved, or disability-adjusted life years (DALYs). One DALY represents the loss of the equivalent of one year of full health. This is then combined with the cost of implementing an intervention to estimate a cost per DALY, or cost per life saved.

This method is how GiveWell estimated that the charities we recommend can each save a life for between $3,000–5,000. They do this by:

- Preventing malaria (Malaria Consortium and Against Malaria Foundation).

- Incentivising routine childhood immunisations (New Incentives).

- Providing supplements to prevent Vitamin A deficiency (Helen Keller International).

Some charities that focus on improving lives through treating parasitic worm infections can similarly lead to an increase of $1,100 USD in additional earnings for each $100 USD donated (SCI Foundation, Evidence Action, Sightsavers, and the END Fund).

There is some uncertainty in these estimates, as the effectiveness of an intervention as measured by an RCT does not perfectly capture the cost-effectiveness in the real world. For example, the cost of implementing an intervention may vary according to the size and scale of the charity. Despite this, these strong and quantifiable estimates are incredibly valuable in determining how much good each dollar donated to charities in global health can do.

Compared to other cause areas, there are more RCTs in global health. As a result, it's easier to perform cost-effectiveness analyses of charities in this area than it is for an organisation whose impact is difficult to measure with an RCT — for example, projects with outcomes that are less tangible, or are further in the future. There is certainly a tradeoff here between a more definite impact, and a less certain (but potentially greater) impact in another cause area that's harder to quantify. This is something to consider when choosing to donate. But if you are looking for a robust and proven way of improving and saving lives, global health is a good choice.

Why might you not prioritise global health?

We think that supporting global health is an evidence-based and cost-effective way of doing good. That said, there are some reasons you might choose to prioritise something else instead.

You might think this is just treating the symptoms rather than the root cause

A common objection to global health interventions is that they only tackle the symptoms of poverty and health inequity, and not the underlying cause — in other words, such solutions are only a "Band-Aid" fix.

Although there may be some merit to this argument, there are a few limitations to this logic that should be addressed.

The first is that the two approaches are not mutually exclusive: we can focus on concrete, tractable things like reducing disease, and also systemic change.3 In fact, there are a number of organisations and causes dedicated to systemic change. In addition, by improving fundamental determinants of health and reducing preventable morbidity and mortality, it is likely that countries with high levels of extreme poverty can then be in a position to empower themselves to contribute to and lead systemic change.

At the same time, we need to consider the systems and structures that perpetuate poverty and inequality. Reforms to health policy may have less immediate and tangible effects, but could have a greater impact on poverty in the long run. Evidence in this field is currently limited, so more research on the effectiveness of work in this area would be valuable. Some areas of health policy reform that seem particularly promising are tobacco control, alcohol policy reform, reducing lead paint exposure, and food policy. If you are interested in learning more about this, see our page on health policy.

You might be concerned about deciding what people from lower-income countries need

A common concern that some people have is that we should be wary of helping people in low-income countries without understanding their situations and needs, and that foreign aid may be perceived as paternalistic and ineffectual.

Foreign aid can certainly be controversial and unethical, if not managed appropriately. Aid has historically been misused to support despotic regimes and compound misery, and has been a weapon for wealthy countries to support their own strategic allies and commercial interests.

However, to paint all global health and development initiatives with such a broad stroke would be a generalisation. Angus Deaton, the winner of the Nobel Prize in Economics, is often critical and sceptical of foreign aid, but says that certain types of foreign aid — for example, offering vaccinations, or developing cheap and effective drugs to treat malaria — have been hugely beneficial to low-income countries. In addition, it would be hard to imagine how we could be "wrong" about the need to prevent suffering or deaths from malaria. Although there are certainly more controversial facets of foreign aid, the most cost-effective and evidence-based initiatives seem to avoid most, if not all, of this concern.

However, if you still have concerns, you can support the approach of GiveDirectly, which sends money directly to people living in poverty, offering agency and empowerment without any strings attached.

Source: SCI

What are the best charities in global health?

Within global health, we recommend GiveWell's top charities.

GiveWell is an organisation that spends around 50,000 hours a year researching and synthesising a wealth of evidence to share their recommendations on the most cost-effective, evidence-based charities within global health. They have an in-depth and independent evaluation process that models the cost effectiveness of each charity, and they also conduct interviews and site visits. They also look at the budget and outcome data from each charity and frequently review any recommended charities to ensure that they continue to meet their criteria.

GiveWell recommends the following charities working to improve global health:

Learn more

- Health in poor countries (80,000 Hours)

- 80,000 Hours' podcasts on global health and development (80,000 Hours)

- GiveWell's research overview (GiveWell)

- Cost-effectiveness analysis for health interventions (WHO)

- If you want to learn more about the field of global health, consider these free introductory courses from Yale University and Johns Hopkins University.

Our research

This page was written by Akhil Bansal. You can read our research notes to learn more about the work that went into this page.

Your feedback

Please help us improve our work — let us know what you thought of this page and suggest improvements using our content feedback form.