Conducting and communicating effective altruist research

A key aspect of effective altruism (EA) is working out how to do the most good. As the EA movement is young, many causes and ideas around doing good are still relatively unexplored. Conducting research into these questions, and communicating our findings, might be one of the best ways we can increase our capacity to do good.

Some of the questions we might ask are:

- What are the best careers to do good?

- What are the most effective ways to improve the world through charity, money, action, and influence?

- How does doing good depend on our moral worldview, and what should inform that worldview?

- What possible interventions and approaches might be extremely important that we don't know about yet?

Given the amount of unexplored ground, it seems likely that there are highly promising ideas that are not yet on the EA community's radar, as well as a lack of measurement and evidence in many important areas.

EA research aims to address this gap by conducting and communicating research that could be influential in changing how we do good.

A core part of EA is being open to new ideas and paths to improving the world. EA promotes a cause-neutral approach that seeks to improve the world in a way that is not attached to any specific issue. Instead, we aim to impartially search for causes that will maximise our ability to do good overall. There is huge potential for more exploratory research to unveil new and promising opportunities to do good. This in turn will help us tackle the world's most pressing problems.

What does EA research look like?

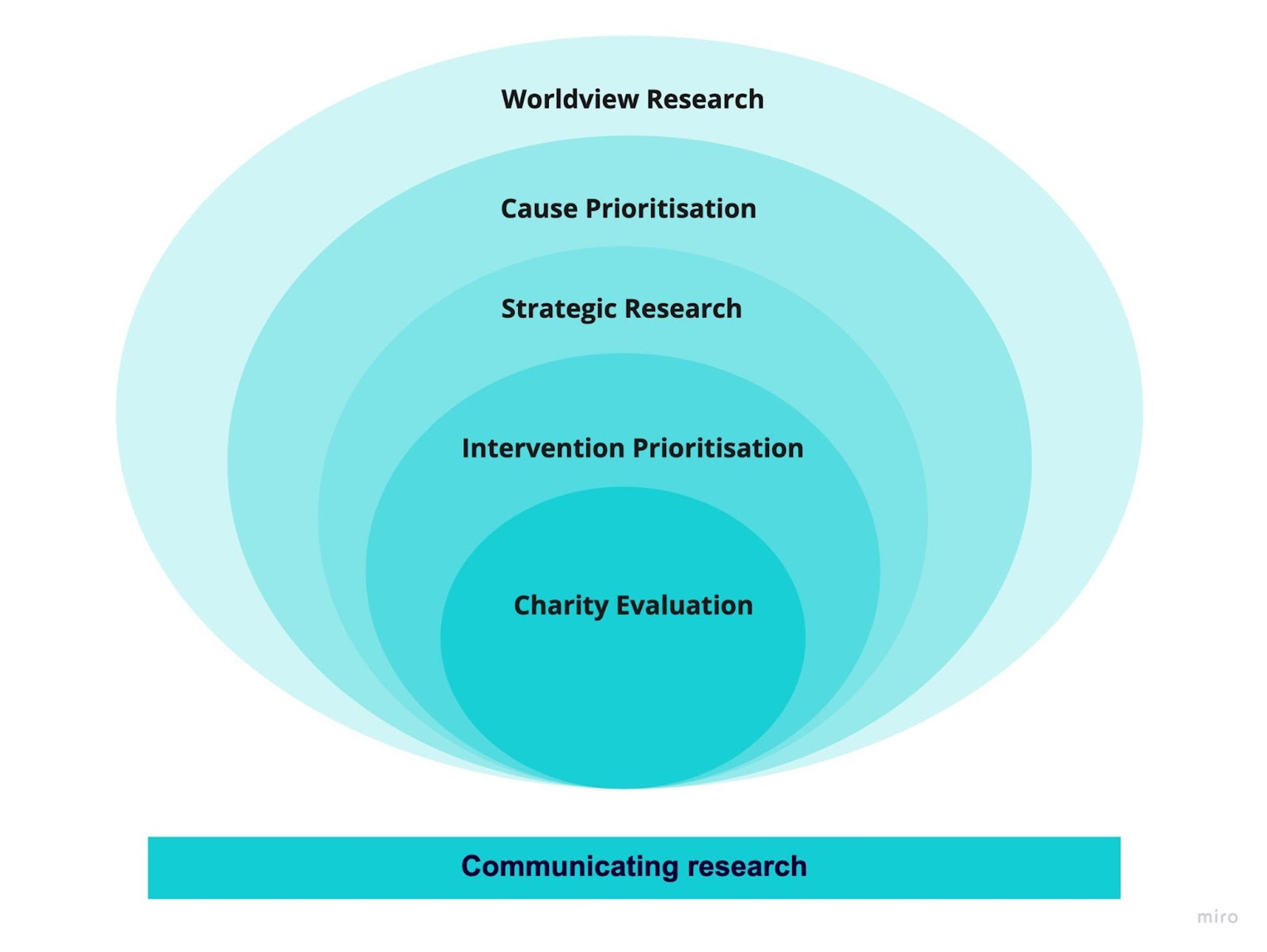

Conducting and communicating EA research can have several different focus areas. A rough taxonomy is below, although the distinctions between the forms of EA research are not clear cut. In particular, there is considerable overlap with global priorities research, especially when it comes to cause prioritisation and worldview research. Similarly, charity evaluations, such as those conducted by GiveWell, often include intervention prioritisation efforts. A visual overview of the taxonomy is further below, developed from this research by Charity Entrepreneurship.

- Worldview research: Research into what or who matters most in the world.

Example: How much should we value people alive now compared to those in the far future? - Cause prioritisation: Exploring, understanding, and comparing the value of different cause areas; and considering and estimating the relative value of additional resources devoted to each in a cause-neutral way.

Example: How important, neglected, and tractable is improving global poverty compared to voting reform? - Strategic research across cause areas: Analysing different high-level strategies to make progress on pressing problems.

Example: How effective is policy advocacy compared to movement building for reducing global poverty? - Intervention prioritisation: Using evidence to determine the best interventions within a certain cause, based on our strategic research.

Example: Is policy advocacy best done via directly lobbying policymakers, encouraging the public to apply political pressure, or by releasing high-quality research? - Charity evaluation: Recommending charities based on the effectiveness of their programmes.

Example: Is Against Malaria Foundation or GiveDirectly a more effective way to help people alive now? - Communicating all the above: Promoting and disseminating key EA concepts to a broad audience. The ideas and research can only have an impact if they're used to inform people's decisions.

Example: 80,000 Hours via their podcast or their key ideas series.

Why is EA research important?

Conducting and communicating EA research may be one of the most impactful activities the EA movement has done to date. Over the past 10 years, we've seen a significant allocation of resources towards newer fields thanks to new research findings.1

In addition to the huge scope for impact, EA research seems relatively neglected. There are some indications (as discussed on the EA Forum and by Charity Entrepreneurship) that there isn't enough EA research being done, particularly in worldview research and strategic research.

What is the potential impact of EA research?

Conducting and communicating EA research has significant potential to alter the trajectory of the EA community. The EA movement has experienced considerable shifts in its priorities over the past few years, with greater resources and community efforts being devoted to safeguarding the long-term future, and it's unlikely that we've already reached the end of our learning.

Given the recent increase in support for newer causes — such as wild animal welfare, building effective institutions, and AI governance — it seems that novel research does influence the priorities of the EA movement.2 Further exploratory research could influence billions of dollars of committed funding to EA going forward.

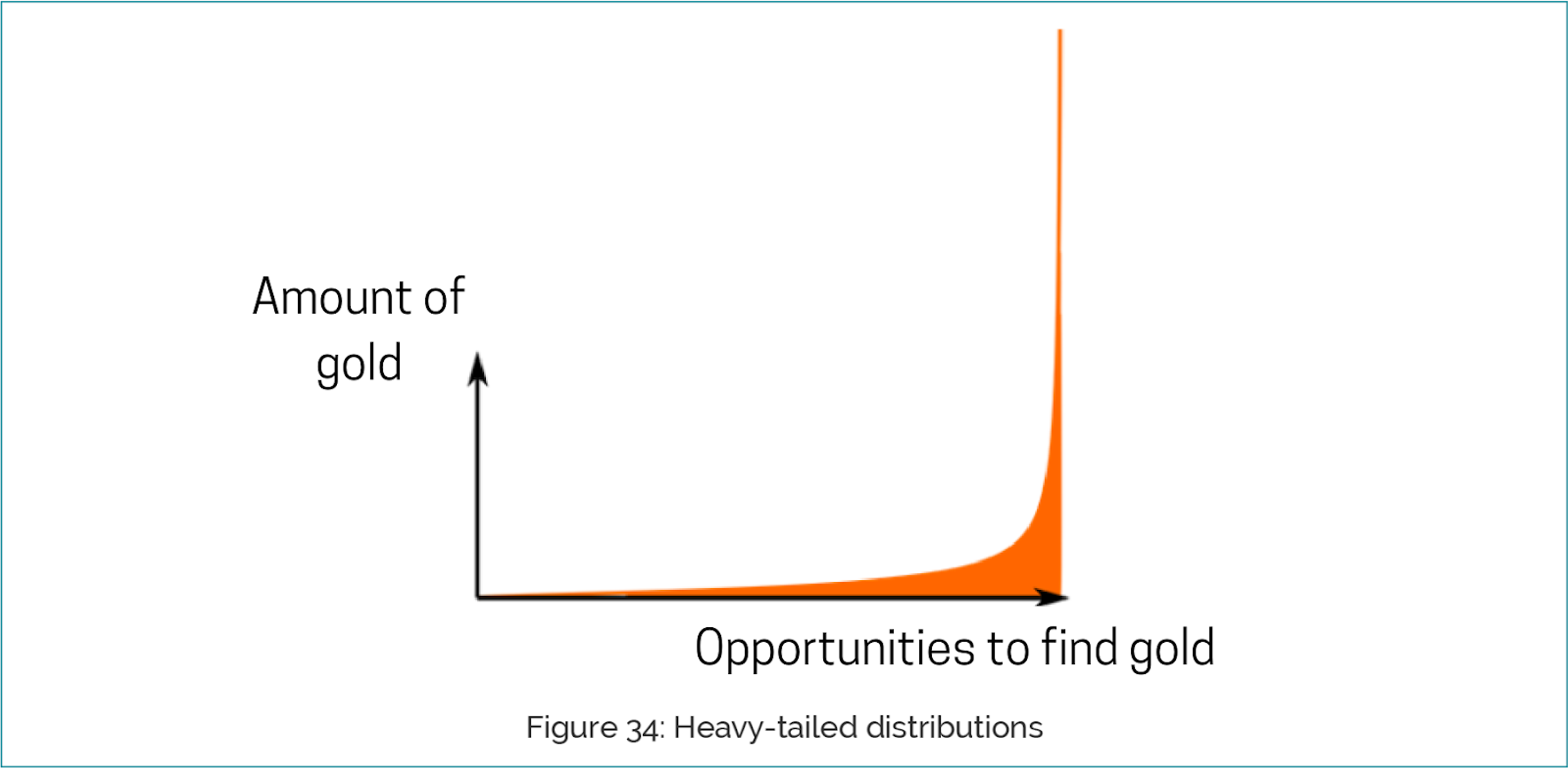

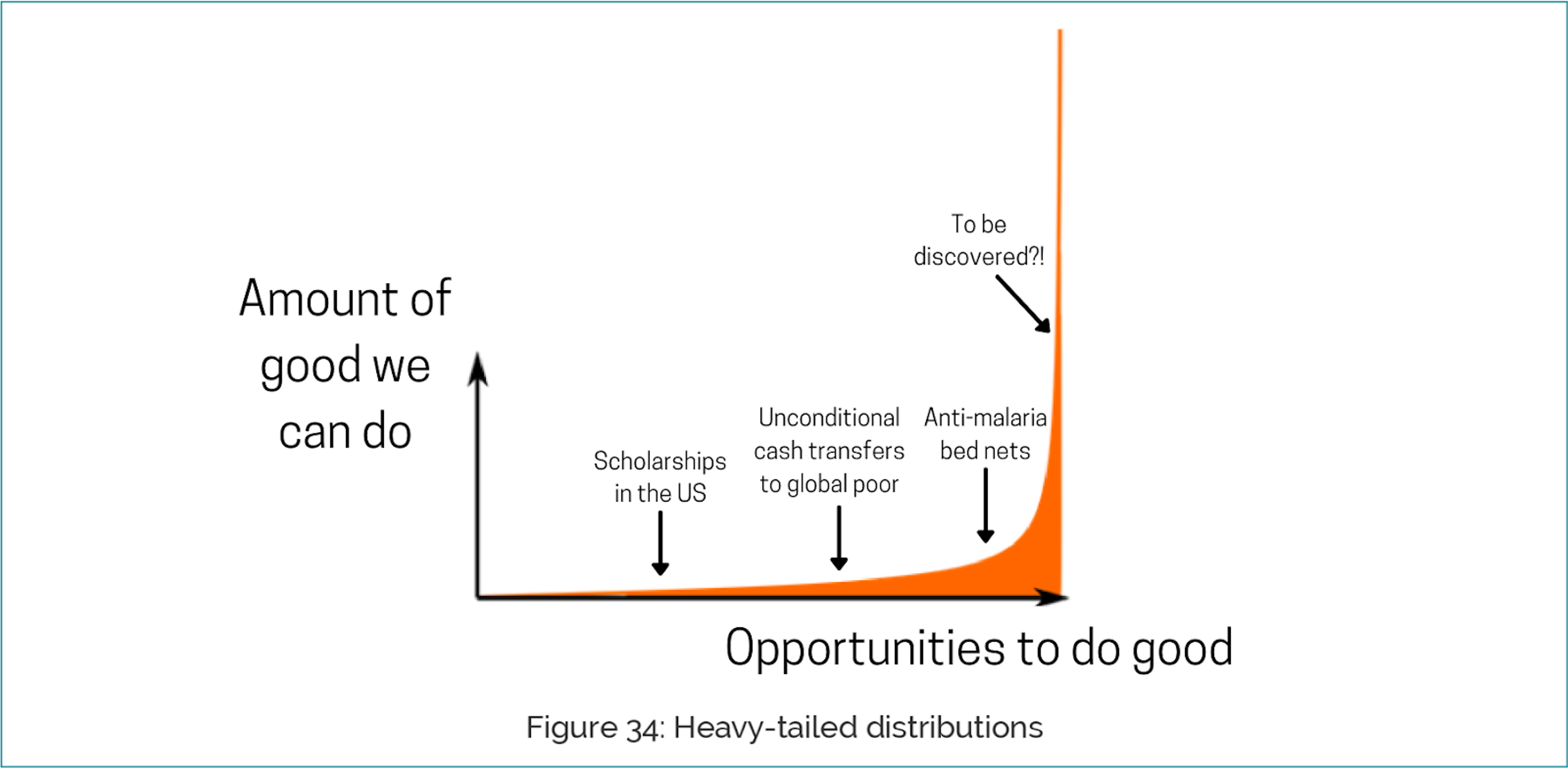

We can think of EA research looking into new causes or ideas as prospecting for gold. Unfortunately, the world does not have a clearly signposted mine where you can extract infinite amounts of gold. Instead, gold is often clumped together in pockets, some much bigger than others, hidden away until it is discovered.

Much like gold, the best opportunities to do good can be hard to find, and some of them are much larger in scale than others. Owen Cotton-Barratt, a researcher at the Future of Humanity Institute, argues that it's likely that most of the good we can do in the world is concentrated in a select few opportunities. Therefore it seems extremely important that we try to identify these opportunities early on and make the most of them. (This style of thinking is also applied in global priorities research, an emerging academic field that aims to understand how we can maximise our limited resources to do the most good.)

The graph above shows the various opportunities to find gold. We see that some opportunities have vastly greater amounts of gold — so we should try to identify those opportunities as quickly as possible.

Applying this analogy to doing good, we can see how moving up the graph towards more effective interventions can be hugely impactful. This is why it's important to keep exploring new ideas — identifying opportunities to have an outsized positive impact on the world.

One example of EA research is 80,000 Hours' research to understand the positive impact of various career paths. They research and write career profiles for impactful roles — such as AI safety technical researcher, founder of new projects tackling top problems, and grantmaker for a philanthropic foundation. In addition, they research how to actually obtain these impactful careers, with a career guide exploring various questions such as how to build up relevant skills, when to explore other options vs focus on one role, and how to balance impact with your passions.

To illustrate the impact of this style of EA research, we can look at the case study of Dr Cassidy Nelson. Cassidy had been a doctor in Australia when she came across 80,000 Hours' research on biorisk and decided that she wanted to move into public health, specifically to assist with the prevention of future pandemics. After receiving career advising from 80,000 Hours, she decided to do a PhD in pandemic modelling, and now co-leads the biosecurity team at the Future of Humanity Institute. She has also consulted with the World Health Organization on health security, and advised the UK Government on their response to COVID-19 and other pandemics.

Most of us would probably already consider being a doctor as a job that helps a lot of people. But the research conducted by 80,000 Hours allowed Dr Nelson to see that she could increase her impact even more: while previously she could only help the limited number of patients she could see each day, she now has the potential to influence the long-term future of humanity and prevent deaths from pandemics in the near term.

Finally, 40 EA community leaders were surveyed about which meta ideas they thought would be the most impactful. Results showed that exploratory research was the meta idea with the highest average score.3 Many believe that this research is core to the concept of effective altruism, and could be done more systematically.

Is EA research neglected?

We can consider the neglectedness of EA research from two angles:

- The allocation of resources.

- The number of unanswered questions.

In terms of resources, EA is currently spending approximately $416 million USD across all causes, yet less than 5% of that is being spent on exploratory EA research.4 Given that this research has the potential to influence billions of dollars within the EA movement (not including wider philanthropic spending), EA research seems neglected relative to the possible upsides.

We can also consider the fact that EA is a relatively new concept, as are real-world attempts to apply the general principles of using evidence, science, and reason to do the most good.5 That means we've only spent 200 years or so trying to figure out the best ways of improving the world using evidence-based concepts.6 Given that humanity has existed for 300,000 years to date (and could exist for millions more), we've only devoted a tiny fraction of our time to answering these challenging questions.

There has already been a significant amount of EA research conducted to date.7 However, considering the amount of potential research needed to understand what causes and interventions are best to work on, there seems to be room for more research. There are plenty of potentially promising focus areas, some with no published research beyond a single forum post. It's important to note, however, that some of this research is also being conducted through global priorities research, other private research organisations, and academic institutions.

On top of identifying new causes, we don't fully understand the causes that we already advocate for, such as reducing global poverty or improving animal welfare. For example, we generally focus on the short-term effects of interventions,8 rather than how they might affect the far future.9 This is because it is extremely challenging to model the long-term impacts of interventions, especially when considering time scales of thousands or millions of years.

However, some argue that the impact of our actions on future generations is much more significant than the impact on those alive today. This could be true for several reasons, with the possible astronomical number of future beings and the vast potential of humanity being key drivers. In this case, it would be vital to understand the long-term implications of our actions today.

For example, we can confidently say that anti-malaria bed nets are an effective intervention to save lives from malaria in the short term. What is much less clear is whether saving a life will be better or worse for the village, country, or world in the long run. For example, saving a life has implications for the population size, which may have long-term consequences for the climate, local politics, animal welfare, and many other areas of life that are difficult to quantify.10 There is no obvious way to weigh these considerations — and different people have wildly different views on the topic, and it's not clear how to reconcile them.

These long-term considerations introduce several uncertain factors, where we're not sure if our actions are good or bad for the far future. The crux of this issue is that these uncertain factors might actually play a greater role in how much good we do, relative to the factors we do understand.11 In short, studying the long-term effects of the interventions we're currently advocating for seems highly important to ensure they have a positive impact on the future of humanity, as well as those alive today.

In addition to intervention prioritisation research that seems neglected, there are many unanswered strategic questions that could affect how we solve globally pressing issues. For example:

- How effective is policy advocacy compared to building grassroots organisations?

- How does direct charity work compare to impact investing?

- How do we best build career capital to have a large impact in our careers in the future?

In summary, although several organisations and researchers are conducting EA-aligned research, there still seems to be a substantial amount of important work that could be done. Given the potential scale and leverage of this research (such as influencing billions of dollars towards highly effective causes), we believe conducting EA research is still neglected.

Is EA research tractable?

This research is difficult to conduct, as the scope is very broad and it often requires interdisciplinary thinking: researchers need to have a good understanding across a range of disciplines, such as economics, philosophy, and psychology.

However, there have been some notable successes in recent years that indicate this research is tractable:

- 80,000 Hours' research and communications work has garnered over 8 million readers since its launch in 2011, leading to 1,000+ career plan changes and therefore 80 million hours switched towards more effective careers.

- Animal welfare within EA has experienced a shift in funding from farmed animal welfare towards wild animal suffering in recent years, due to research produced by Wild Animal Initiative and Rethink Priorities highlighting the huge scale of suffering experienced by wild animals.

- There are now increased efforts going towards mental health and improving subjective wellbeing, thanks to the work of Charity Entrepreneurship and the Happier Lives Institute.

- Research conducted by Founders Pledge showed that supporting low-carbon technology innovation is one of the most cost-effective ways to reduce global carbon emissions and reduce extreme risks from climate change. As a result of this, EA climate funding and efforts shifted from rainforest protection organisations towards think tanks that advocate for policies that boost low-carbon innovation.

Why might you not prioritise EA research?

You think we've already found the best causes, interventions, and other ideas

You might think that we're quite far along in finding the best opportunities, so additional efforts here might not be that fruitful.

While this could be true, it seems unlikely. Given that the EA movement is just over 10 years old, it's hard to imagine that we've figured out all the best ways to improve the world in such a short time. In just the last few years, we've seen EA research that has shifted our priorities (such as towards wild animal welfare or low-carbon technology innovation), so there are still large shifts happening. In addition, even if we've identified the best causes and concepts, there is still essential work in communicating this research so we can successfully steer resources in more effective directions.

The research might not actually change anything

Even if research is conducted that clearly shows one idea is more effective at improving the world than another, there's a risk that these findings might not be acted upon. There are a variety of reasons this might happen. For example: the research doesn't reach the correct decision-maker, the decision-maker doesn't understand the research, or even just reluctance to change existing practices.

While this concern is plausible, the examples in the tractability section above highlight several cases where EA research has been instrumental in shifting our priorities. This may not extend to every case, but it shows there is clear evidence for it working. Specifically, good communication — clear presentation of the findings and wide dissemination — can increase the impact of EA research, by making sure the relevant people hear about and understand the research in question. This increases the likelihood of it being acted upon, making research communication a fundamental component of conducting and communicating EA research.

The questions are too difficult to solve

You might think this sort of research is too challenging, without guaranteed results that would improve the world. Organisations and individuals conducting this research would need to have a very broad understanding of the world and a highly interdisciplinary skillset, which are not easy to find.

While it's true this work will be challenging, the potential upsides of conducting it seem to outweigh the lower possibility of success — both the scale (potentially billions of dollars influenced) and neglectedness are quite significant. Using the principles of hits-based giving, the total expected value of how much good we can do (even with low likelihood of success) is still significant enough to be worth exploring further.

In addition, successful work in this area has already been conducted by organisations such as Founders Pledge and Charity Entrepreneurship, so this is an indicator that it is tractable.

What charities, organisations, and funds can you support?

You can donate to several promising programs working in this area via our donation platform. For our charity and fund recommendations, see our best charities page.

Learn more

- Prospecting for gold (Owen Cotton-Barratt)

- The case of the missing cause prioritisation research (Sam Hilton)

- Exploratory Altruism Report (Charity Entrepreneurship)

- Research Agenda (Global Priorities Institute)

Our research

This page was written by James Ozden. You can read our research notes to learn more about the work that went into this page.

Your feedback

Please help us improve our work — let us know what you thought of this page and suggest improvements using our content feedback form.