An update on the effectiveness of Deworm the World Initiative (DtWI)

The Deworm the World Initiative (DtWI) has been one of our highly recommended charities for several years now.

Our colleagues at Givewell have published an extensive update recently that was generally very favourable, and they continue to rank among Givewell’s top charities. You can read more about the general case for deworming on Givewell’s page on deworming.

In this blog post, we will give you an update about their efforts that we feel complements Givewell’s report. You can find more general information about DtWI on our website. In our opinion, DtWI continues to be a very promising charity and could be one the most effective charities in the world.

Recent Scientific findings that relate to DtWI’s effectiveness

New findings on whether deworming improves health and cognition

DtWI has traditionally focused on deworming programs in India, where soil-transmitted intestinal worms (soil-transmitted intestinal helminths (STH)) are very common and there is almost no schistosomiasis, which is generally considered to be more harmful. The main STH parasitic worms that infect people are the roundworm (Ascaris lumbricoides), the whipworm (Trichuris trichiura) and hookworms (Necator americanus and Ancylostoma duodenale).1 However, recently DtWI has expanded their deworming program into Africa, namely Kenya and Ethiopia, where schistosomiasis is common and where they help with combination deworming programs against STH and schistosomiasis (we have previously reported on how location matters for deworming [insert link to Eliz post]). Moreover, DtWI is currently thinking about expanding into other African countries such as Nigeria, Namibia or South Africa.2 Hence we will focus our review mainly on new research findings on the effects of only treating STH and refer to our previous update on the Schistosomiasis Control Initiative for new findings relating to combination deworming programs treating STH and schistosomiasis [insert link].

Effects of deworming for treating soil-transmitted intestinal worms on health

A recent Cochrane review summarized studies looking at the effects of deworming drugs for treating soil‐transmitted intestinal worms on nutrition and school performance3. They suggest that deworming may increase the weight of children by over half a kilo and increase haemoglobin levels. It is possible that cognition is improved, but this is based on a few low-quality trials, and Givewell argues that they should have included another trial. Crucially, all of the evidence comes from small trials studying children known to be infected with worms (by screening). In contrast, without prior screening they conclude that it is unclear whether mass deworming of STH is has an effect on weight, height, school attendance, or school performance; and that it may have little or no effect on haemoglobin or cognition. This study has been criticized by Poverty Action4,5 and a rebuttal of that criticism has also been published6. We generally believe with this rebuttal and that the inferences drawn in the Cochrane review are generally valid.

Moreover, a recent analysis of DEVTA, a large scale cluster-randomized trial from 1999-2004 with 1 million lightly infected Indian children from rural areas7, found weight, height, and haemoglobin were not significantly improved by mass deworming. They furthermore found that in this lightly infected population reduction in mortality could be anywhere from no reduction to 10% reduction in mortality (the overall mortality was 2·52% and 2·65% in the treatment and the control group respectively). It could however be more likely that deworming affects mortality in other, more heavily infected, populations. This trial also had a potential confounder: some children with obvious worms in the control group received treatment8. We believe this is a minor confounder and does not jeopardize the main conclusion drawn from this trial.

However, generally, there is agreement, even among the authors of the Cochrane review and the large DEVTA trial that did not find strong evidence for health benefits on mass deworming 9,10 that children who were screened for worms and test positive should be dewormed and that, in principle, deworming drugs for STHs have good, reasonably strong effects on health, which is in line with our biological understanding of the parasitic worms. So the question is: if there is consensus that the deworming works in principle, then why don't we see reasonably strong effects of mass deworming in the Cochrane meta-analyses on mass deworming and the very large DEVTA trial? There are some sensible explanations:

- The large DEVTA trial, which was conducted between 1999 and 2004, was confounded (see above) and/or conducted suboptimally, since it did not include integrated measures to reduce infection such as hygiene promotion (which is now considered to be best practice for deworming interventions), or it did not deworm frequently enough.

- The true effect size of mass deworming on populations with all kinds of infection intensities and prevalence is underestimated because the samples studied had relatively low worm burden.

- The trial was not adequately powered to pick up a relatively small effect size on health measures (in fact, the large trial was no better powered than several previous studies to pick up effects on health indicators, but only highly powered to pick up effects on mortality11)

Crucially, screening followed by treatment of those children testing positive for worms is far less practical and more costly than mass treatment of infected and uninfected children without diagnostic testing12. In the light of this cost-benefit analysis for screening versus mass treatment, the case for mass deworming is still strong, but one might suggest that it is better to focus more on more heavily infected populations and improve trials. Because DtWI provides technical assistance and evaluation of whether an area should be dewormed based among other whether the local worm burden is sufficiently high, they have probably improved the effectiveness of mass deworming programmes in the more recent past.

Effects of deworming for treating soil-transmitted intestinal worms on cognition

A recent reanalysis of data from a cluster randomised trial compared the literary and numeracy test scores of children 7-8 years after mass deworming for STH to the scores of a control population which had not undergone mass deworming during this time period13. The author found improved test scores in those treated with deworming, and concluded that this strengthens the evidence for cognitive benefits for mass deworming in areas of high worm prevalence. Even though this analysis is not perfect (we have reported about this previously), we do believe that the analysis is valid and we support its conclusion.

Another recent paper14 looked at deworming spillovers during early childhood and suggests that there are improvements in cognitive performance equivalent to between 0.5 and 0.8 years of schooling. However, this paper looked at combination deworming. Givewell conducted a reanalysis of this data looking at the effects of STH by excluding all the schools that received praziquantel against schistosomiasis. They find that not all but many of the results still hold15, which means that DtWI’s case of only deworming for STHs in India is still strong with regards to improvement of school performance.

Does deworming against STH increase malaria intensity or prevalence?

We have previously written about how mass drug administration against Schistosomiasis might help reduce Malaria. However, with STHs the case is very different. Researchers have long been aware of the fact that worms significantly impact malaria16. Increasingly, STH - Malaria co-infections have been the focus of investigation and some scientists have become worried that certain STHs actually protect against malaria. There are several reasons to believe that certain intensities of some STHs actually protect people from malaria and thus there is a worry that deworming might make people more susceptible to malaria. There are several reasons for why one could assume this. The default condition of the mammalian ancestral immune system was to be parasitized by gastrointestinal worms (schistosomiasis is not a gastrointestinal worm)17. Malaria is one the strongest known selective force on the human genome18. Based on our knowledge about the human immune system, it is plausible to assume that malaria and helminths interact19. There are at least 20 studies that examine interactions between malaria and worms in humans (for a recent review, see 20).

One recent review concludes that that some worms, notably Ascaris, are associated with protection from severe complications of malaria and that others, notably hookworm, lead to increased malaria incidence or prevalence21. Other factors might include the worm infection intensity, as well as age22 on the outcome of co-infections23 (age is potentially a very relevant factor for DtWI, which mostly deworms school age children, who are also more vulnerable to malaria, but the literature does not currently have a consensus on this topic24). A recent paper25 has even suggested that mass drug administration should administer both ivermectin, an antimalarial drug, and albendazole, which is used for deworming, in order to maximize effects against STHs and malaria.

To what extent is the interaction between Malaria and very specific worms relevant to DtWI? In the past, DtWI has primarily operated in India and has only recently expanded to Africa (Kenya). Treatment against schistosomiasis with praziquantel has been suggested to decrease the incidence of malaria26. However, in India, schistosomiasis is not present but STHs such as Ascaris and hookworm are. In some of the Indian states that DtWI operates in, Ascaris (which has been hypothesized to decrease malaria susceptibility) is more prevalent and intense than hookworm (which has been hypothesized to increase malaria susceptibility)27,28. Moreover, about 95% of Indians reside in areas where malaria is endemic29. Thus, there is a case to be made that deworming could increase the malaria burden, but due to the complex interactions between worm-load, the kind of worms, prevalences, and reduction, it is unclear whether t DtWI STH deworming has increased or decreased malaria incidences, severity and morbidity. Further research is needed to address this question.

However, some researchers caution30:

“Although it is tempting to rush to the conclusion that deworming patients would reduce malaria [due to Hookworm and schistosomiasis], it still seems wise to be attentive to the potential scenario of an increase of severe malaria [due to protective effects of Ascaris]. Monitoring the incidence of malaria and severe malaria before and after vertical de-worming campaigns seems a minimum test to make sure there is a better understanding of what is going on at a population level”.

Others write31:

“The risk that entire populations may have an increased susceptibility to Plasmodium should invite study regarding the possible epidemiological relevance of helminth infections and the impact of controlling them on malaria incidence. The presence of helminth infections could represent a much more important challenge for public health than previously recognized.”

This is interesting in the light of the large scale DEVTA trial with 1 million school children mentioned above32, which did not provide significant evidence of an effect of deworming on survival (mortality RR 0·95, 95% CI 0·89–1·02), which could be due to increased malaria incidences. The confidence interval (0·89–1·02) of this trial does not exclude a mortality reduction of about 10%, but it also does not exclude a very slight increase of mortality. One can also not rule out that positive (e.g. hookworm related) and negative (e.g. Ascaris related) malaria interactions have cancelled out. More research is needed to address this complex issue. Update August 2015: A recent randomized trial suggests that deworming with albendazole does not increase malaria incidence among children 33.

Independent of whether deworming does indeed increases malaria, the topic of this disease interaction was superficially treated in a recent paper34, which has a DtWI Director as the first author. The paper merely states that deworming may also strengthen the immunological response to other infections, such as malaria, whereas the extant literature suggests that the opposite could also be true (see above). Especially in the light of the fact that DtWI is currently seeking additional funds mostly for research, this omission has decreased our confidence in DtWI.

Is Givewell’s concern that they are deworming twice annually justified?

In their most recent report Givewell has been concerned that some of the deworming DtWI has initiated is redundant, because India runs an existing program to treat lymphatic filariasis (LF) where the same drug used to treat STH is sometimes used to treat LF, 35,36. In at least one case, both ran a deworming round within two months. Of course, deworming programmes would ideally be coordinated so as to optimally spread it over the year. However, increasing the number of deworming rounds is probably beneficial and in the following section we present several studies that show that more frequent deworming may be beneficial.

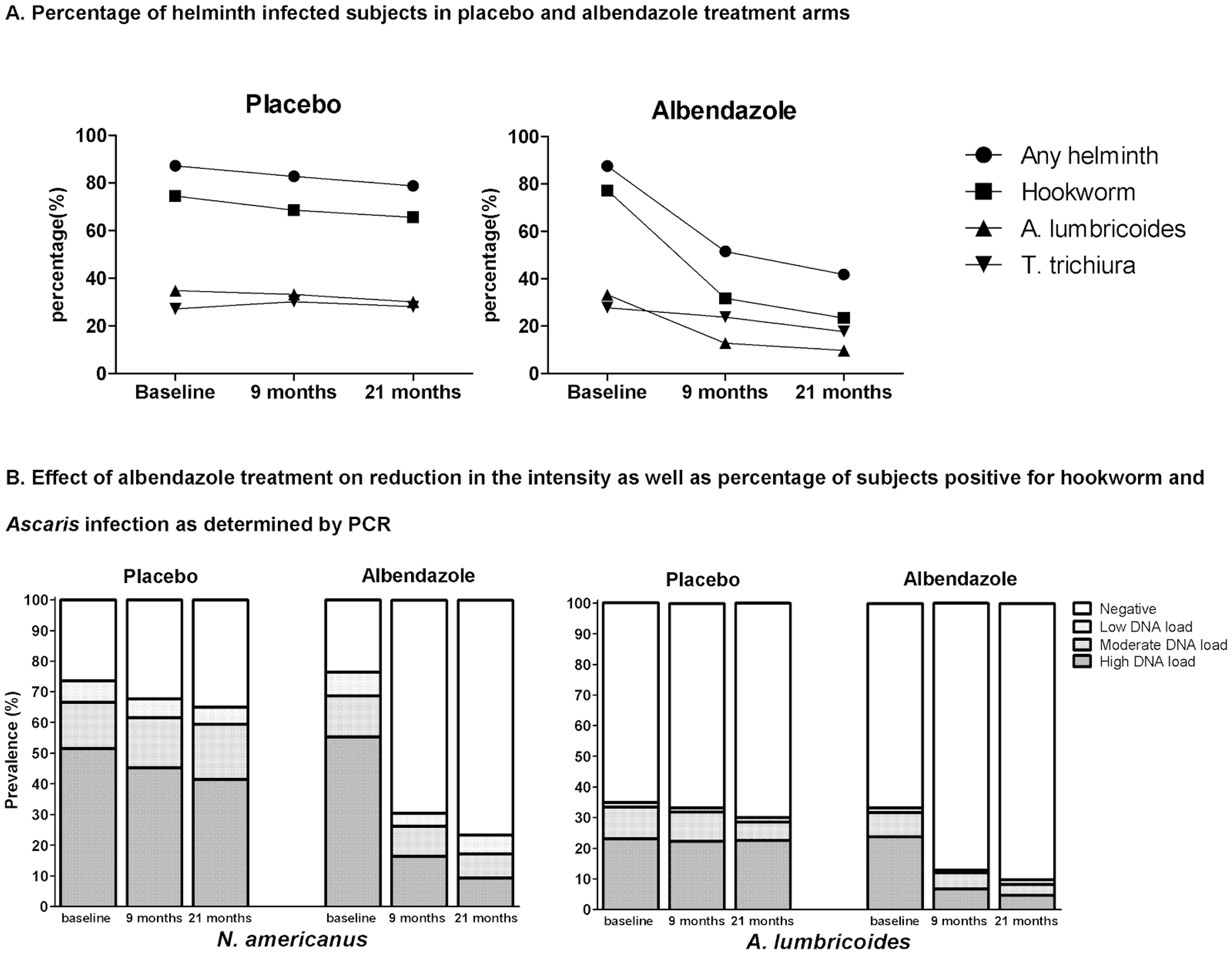

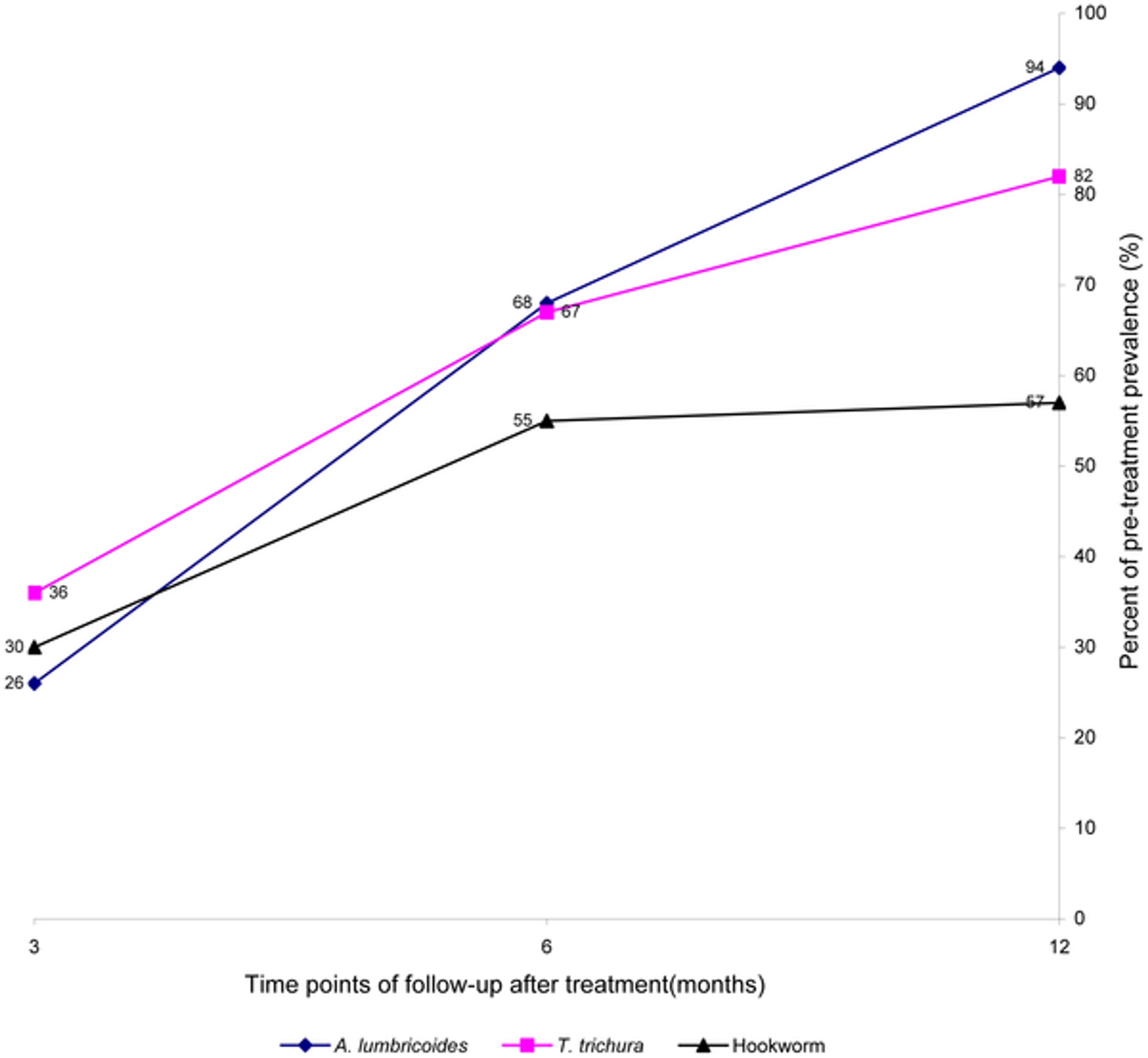

A recent review showed that in endemic areas where the prevalence of STH infections is above 10%, reinfections occur rapidly after treatment (see Figure 1A, B and C), particularly for Ascaris and whipworm and biannual treatment might be indicated against Ascaris and whipworm and at least one treatment per year against hookworm37.

Figure 1A and 1B

Figure 1C**: Summary of the rapidity of re-acquiring soil-transmitted helminth (STH) infections after treatment**

**Notes:**6 months posttreatment, the prevalence of all three worm infections reached or exceeded half the initial level; and at 12 months posttreatment follow-up, the prevalence of Ascaris_ lumbricoides_and T. trichiura usually returned to levels close to the initial pretreatment, while levels of hookworm reinfection continued to fluctuate at about half pretreatment level. Figure taken from38

Another recent study showed similarly rapid re-infection with after 97% of people were cured of Ascaris, the prevalence 6 months post-treatment was back to 83.8%39. And a further recent trial found that in a community where STH are highly endemic, an extremely intensive anthelmintic treatment, which was 3 monthly albendazole administration for 21 months over two years, is safe and leads to a reduction in STH40.

The authors of the review cited above suggest that more intense treatment is likely to further impact on morbidity, but might bear the risk of drug resistance development.

Drug resistance seems to a be a more general concern as it is of yet uncertain whether the reports on reduced efficacy in hookworms represent genuine cases of genetic resistance or whether they simply reflect reduced drug efficacy41.

Finally, there is the question of whether multiple treatments per year are not only effective, but also cost effective. We cannot currently say much about this with complete certainty. One could imagine a case where the the first of a yearly treatment causes a higher reduction in worm load than the second and thus one should do deworming annually. However, our best guess is that multiple treatments are cost-effective. This is because reinfection is often rapid and so treatment after only 3 months seems to have benefits that are not substantially less effective at driving down infection prevalence as treatment after 1 year. The cost for DtWI for executing their deworming programmes seem to be to a large degree upfront costs to get the program running, and we think the marginal cost of having a deworming program more frequently per year vs. just annually is probably low. In sum, we believe that several treatments per year are both effective and cost-effective and DtWI might investigate this possibility further.

Updates on Room for additional funding

DtWI estimates that total cost per child dewormed is about $0.30-$0.40 depending on the country, which is very cost-effective. However, DtWI does not currently execute deworming campaigns directly, but advocates mass deworming and assists local governments to undertake deworming interventions.

The recent Givewell report on DtWI estimates that DtWI has room for $1.3 million of additional funding to support its activities in 2015 and 2016. At a recent meeting Givewell has stated that they hope that they can receive roughly $750,000 in 2014 from Givewell donations42, leaving a funding gap of a relatively small amount of $550,000. In Givewell’s most recent Room for more funding estimations43, they state that December 2014 to March 2015 DtWI has received an additional $660,000 through Givewell.

However, Givewell also states that unrestricted funds have and will continue to allow DtWI to be more strategic in its scale-up.

We agree and have recently argued that there is much more room for funding for deworming organisation such as SCI. DtWI is in a similar position to SCI, in that it could use a lot more resources to scale up its operations and leverage its already existing expertise in order to help tackle the big problem of parasitic infections.

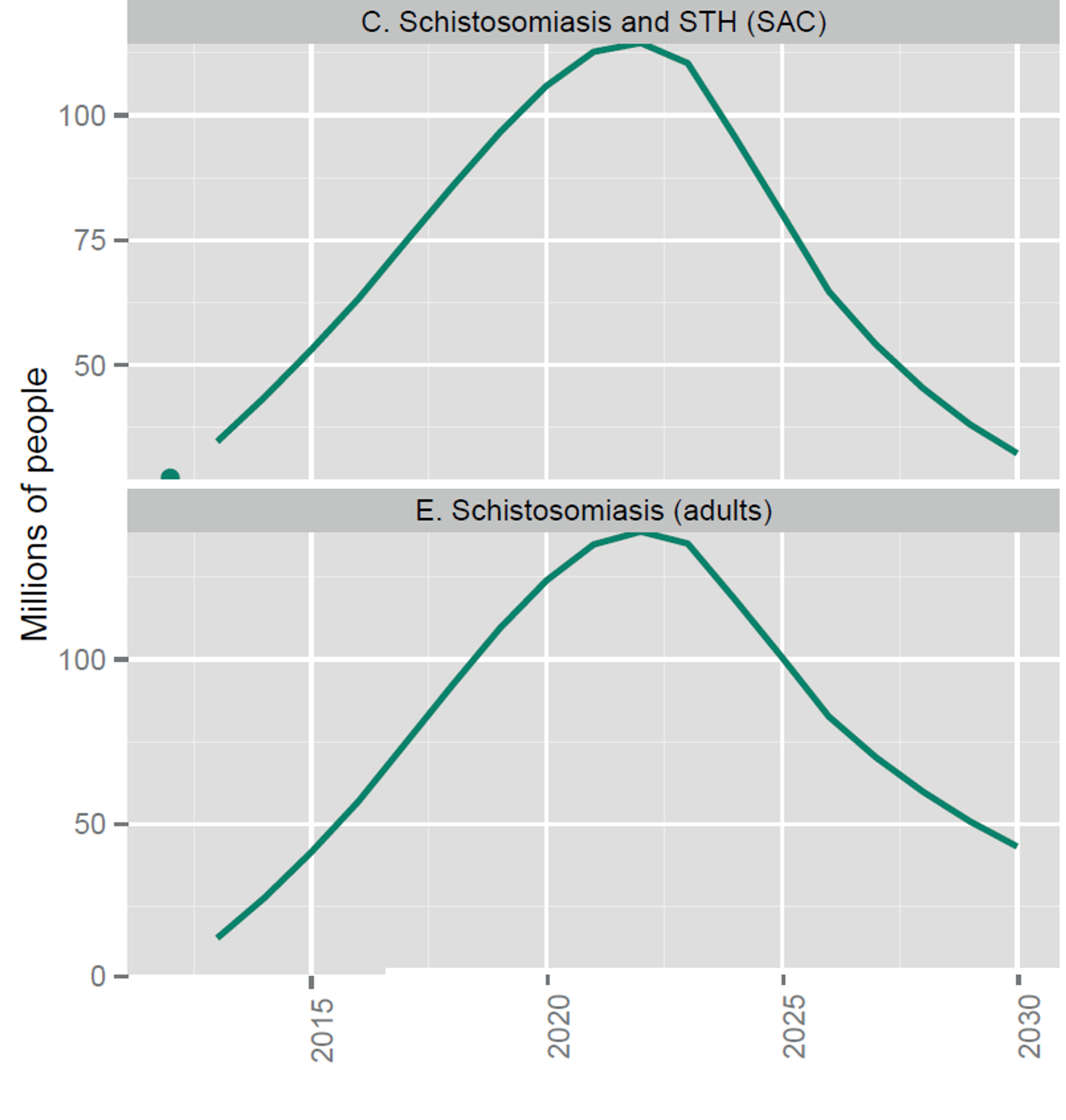

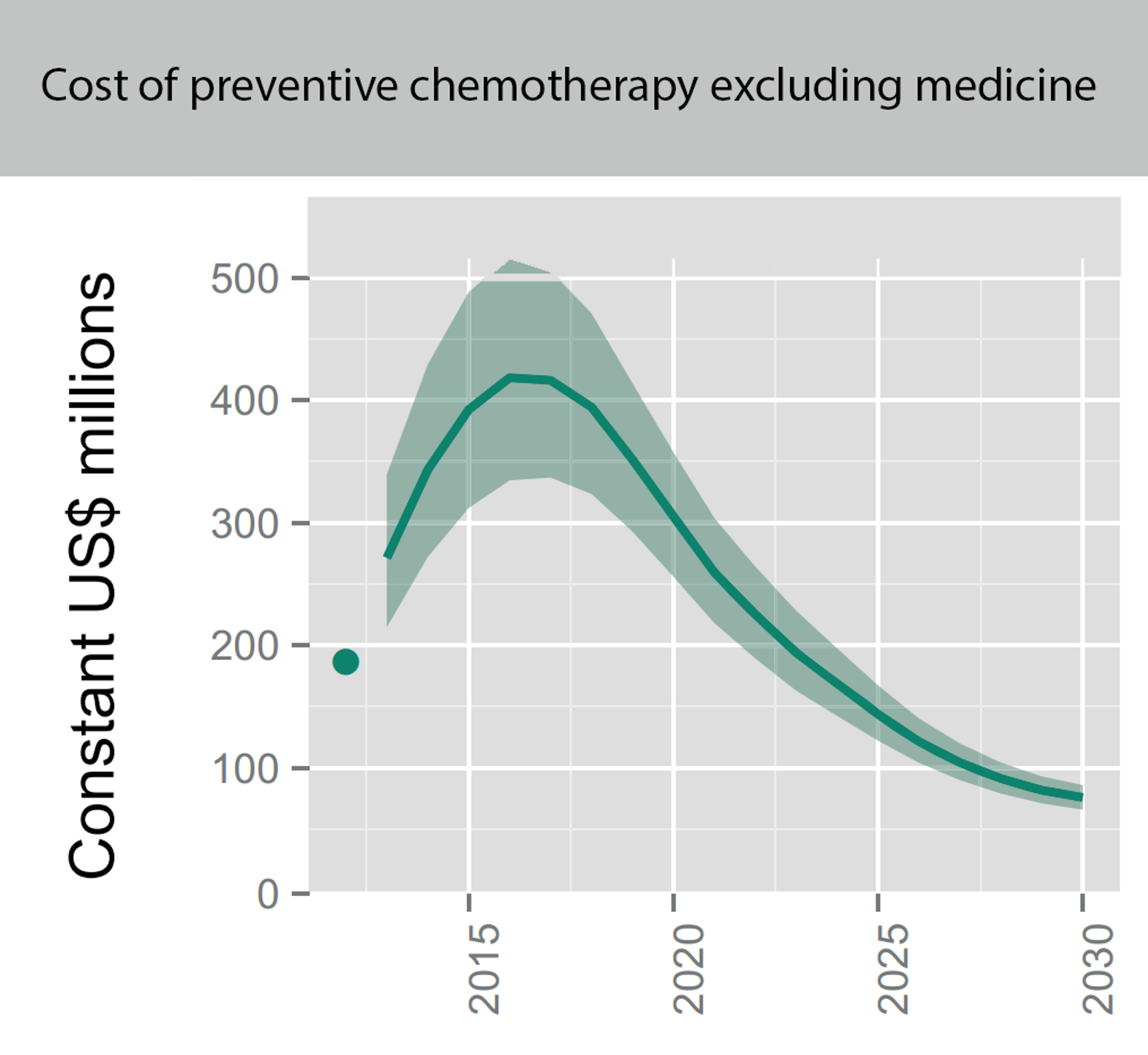

As the number of people who are targeted to receive deworming rises (see Figure 2), DtWI could probably scale up and strengthen its efforts in the countries they currently operate in and expand to new countries. A recent report by the World Health organisation estimates that the overall costs for all kinds of preventive chemotherapy in the coming year are in the hundreds of millions (see Figure 3; see Figure 4 for a split between the costs of Schistosomiasis and STH). As DtWI now also operates in Kenya, the calculations made for SCI (insert link to SCI report) could also apply to DtWI’s operations in Africa. For their continuing work in India, a lower-middle income country, the following calculations already take into account that India completely covers the cost of distributing the donated medicines using their own resources and thus only needs technical assistance and nudging to implement deworming programs.

A recent WHO report44 on NTDs highlights the importance of not neglecting lower-middle countries such a India:

“Until relatively recently, the highest number of people affected by NTDs lived in low income countries. As their economies grew, some were classified as middle-income countries. However, the health and welfare benefits of economic growth have not reached everyone. [...] most (about 65%) of the people requiring treatment for NTDs live in middle-income countries. Indeed, it is even the case that most of the people requiring but not receiving treatment for NTDs are in middle-income countries. Figure 5 shows that the gap between the number of people requiring preventive chemotherapy and the number of people receiving preventive chemotherapy is largest for those middle-income countries – specifically lower-middle-income countries [such as India].”

Thus, it is very much conceivable that DtWI, with their unique expertise in India, might play a substantial part implementing such future deworming programs and thus require substantially more funds. This could be subject to change if bigger agencies such as USAID recognize the cost-effectiveness of interventions targeting NTDs.

Fig. 2: Number of people targeted for coverage with integrated preventive chemotherapy, selected NTDs (from recent WHO report45 on NTDs). Note that the upper graph’s x-axis starts 25 Million.

Figure notes: school-age children; STH, soil-transmitted helminthiases.

Notes: The dots indicate the number of people treated in 2012; the solid lines are targets not forecasts. Targets assume integrated delivery of preventive chemotherapy for LF and onchocerciasis in Africa, schistosomiasis and STH among school-age children, and LF and STH outside Africa. Pending further evidence, they do not yet assume further integration of LF and onchocerciasis in Africa with schistosomiasis and STH.

Fig. 3: Figure showing the overall projected costs of all preventive chemotherapy (i.e. mass drug administration against NTDs including schistosomiasis and soil transmitted helminths) in the coming years. This excludes medicine prices, which are donated by the pharmaceutical companies. Figure adapted from (Fig. 2.4 Investment targets for universal coverage against NTDs from recent WHO report46 on NTDs).

Fig. 4: Figure showing the projected costs of preventive chemotherapy against schistosomiasis (upper panel) and soil transmitted helminths (lower panel) in the coming years. This excludes medicine prices, which are donated by the pharmaceutical companies. Figure adapted from a recent WHO report47 on NTDs.

Notes: Shaded areas reflect the range determined by low and high values of the unit cost benchmarks; they do not reflect uncertainty about future rates of scale-up and scale-down of interventions. The dots in 2012 are actual numbers reported (when available) multiplied by the unit cost benchmarks, which is the approximate cost of delivering one treatment; these are not actual expenditures, but can be thought of as a benchmark for actual expenditures. All numbers expressed in US$ are constant (real) US$, adjusted to reflect purchasing power in the United States of America in 2015.

Figure 5

Notes: World Bank classifies India as a lower-middle income country (more than US$ 1045 but less than US$ 4125 GNI per capita), while Kenya is a low income country (of US$ 1045 or less). The middle-income group includes both lower-middle-income and upper-middle-income countries. Income groups are held constant across the period of analysis. The dark solid line is the number of preventive chemotherapy treatments required for populations at risk of infection and the light dotted line is the number of treatments delivered. The distance between those lines is the coverage gap. The period 2013–2015 (light solid line) is based on an assumption of linear scale-up from actual coverage reported in 2012 towards 2020 targets; these are targets, not forecasts.

The WHO further states:

“The commitment of foreign donors and community volunteers to NTD control will continue to be important in scaling up access to those products that are available. However, it is unlikely that they can mobilize resources at the scale implied by universal coverage against NTDs. Universal coverage against NTDs will fail if it fails to mobilize domestic investment.”

Figure 6

The case for funding scientific evaluation

DtWI plans to spend $230,000 on staff to support evaluation of DtWI’s work in Kenya. Givewell reports48 that this work is primarily funded by CIFF. However, Givewell sees room for more funding:

“DtWI believes that additional resources can improved significantly the quality of the analysis done regarding the cost effectiveness of breaking transmission. One idea that DtWI has investigated is the possibility of distributing bednets along with deworming pills in schools as an alternative distribution mechanism to national net distributions. Another is including hand-washing educational programming alongside deworming days.”

As schistosomiasis related illness is more severe, we believe it is possible for DtWI to expand out into schistosomiasis endemic African countries such as Kenya. This might have a better cost effectiveness than programmes in STHs endemic countries such as India. We also commend the intent to execute and study more comprehensive interventions that treat multiple diseases, as it is generally acknowledged among researchers that WASH (Water, Sanitation, Hygiene) interventions play an integral part to prevent rapid reinfection49.

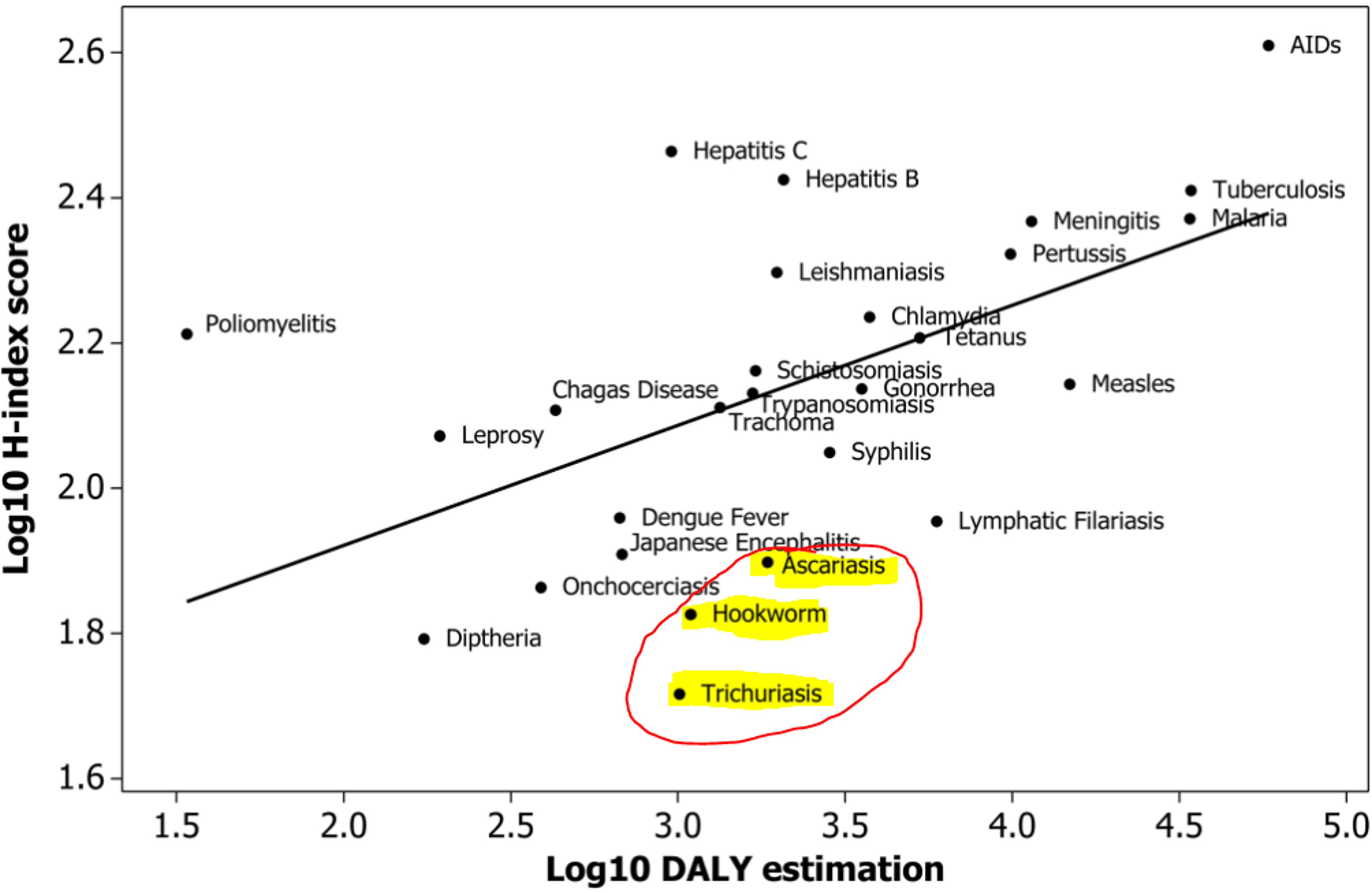

DtWI is planning to spend a large part of their budget - $500,000 of 1.3 million - on evaluation of new evidence-based programs that improve deworming operations50. We are not entirely clear of exactly what of programs DtWI are trying to study, but given its good track-record in research, we think that this is laudable. Moreover, it might be important to study STHs because they are particularly understudied: Figure 7 plots the scientific engagement with a particular disease against the overall burden of a disease51. Figure 7 can easily be interpreted: a disease such as HIV might have a high overall disease burden, but also be focus of intensive scientific investigation, and thus it will be plotted above the line. Diseases that are very close to or on the line, receive scientific attention commensurate to their disease burden. Other diseases, however, which fall under the line, arguably receive too little scientific attention relative to their disease burden and deserve further attention from the scientific community. This measure is of course only a proxy for the degree of scientific engagement and has weaknesses (see discussion of52), however, citations are generally considered to be a good measure of engagement with a certain research area. All STHs that DtWI treats in India are very far under the line (marked in yellow and circled in red) and so are probably understudied. Thus, investment in the study of such disease might be a low hanging fruit with high returns on investment.

Figure 7: Relationship between burden of disease in log10-transformed Disability-adjusted-life-years (DALYs) and H-index scores. Figure adapted from: doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0019558.g003

Updates on Fundraising activities

DtWI has been very successful at receiving funding from governmental and non-governmental organisations. In 2014, CIFF, a major foundation that had supported DtWI's programs in Kenya, agreed to a 6-year, $17.7 million grant to support DtWI's expansion to additional states in India and technical assistance to the Government of India for a national deworming program53.

DtWI’s Executive Director has reported that they are currently in conversations with donors to close a funding gap for their Dispensers for Safe waters project, which leads us to believe that they are actively seeking out additional funds from private donors and foundations. 54

Updates on Expertise

Recently, DtWI plans to hire more staff for their operations. In their budget they plan to spend $50,000 to hire a senior epidemiologist55. We believe that it reflects well on DtWI that they continue to expand their team with the needed expertise.

Updates on DtWI’s Operations

DtWI is part of Evidence Action. Evidence action includes not only DtWI, but also a program called Dispensers for Safe Water (DSW). One issue in terms of donation with this is that even though one can currently donate to DtWI directly on Evidence Actions website, Givewell believes56 that donations might indirectly support the DSW project as well and that realistically one cannot currently donate only to DtWI. There are two problems with this. First, in order to estimate DtWI would require two separate cost-effectiveness analyses that would have to be averaged, which is hard. Secondly, and perhaps more importantly, the evidence does not currently suggest that interventions to reduce diarrhea by improving water quality through chlorination in developing world are effective, as diarrhea is endemic and hygiene is poor57. However, since Evidence Action projects to spend a $10.1m of its total budget of $17.2 million on DtWI58, the lower bound for its effectiveness, assuming that its other projects are entirely ineffective, is just its DtWI’s effectiveness multiplied by .6 (=10.1/17.2), and a reduction of DtWI’s effectiveness by 40% would still mean it is very effective as compared to other health interventions. This relies on the assumption that marginal donations to DtWI would be shared equally between DtWI and Dispensers for Safe Water (50-50 split).

In the past DtWI has been criticised by Givewell over their monitoring and evaluation processes. In late 2014, they developed a comprehensive strategy to improve on this issue. Their proposal59 states that DtWI has now started a competitive request for proposals (RfP) process to identify a professional survey organization to provide independent monitors. Their RfP has a good set of requirements to ensure that the data quality is good. We believe that this is a very good way of addressing Givewell’s criticism. Moreover, they have outlined a strategy for quality assurance of their training programs of their health workers, which Givewell had previously believed to be poor. Now, DtWI will assess training quality through a variety of means. For instance: there will be a pre and post test checkup, with questionnaires administered by DtWI staff checking key messages about deworming, at both the district level and the block level. They have also improved on their strategy to increase the quality of government reported data, by improving forms, greater integration with existing school health reporting structures and forms, and cross validation of data to check the veracity of reported numbers in the whole school.

DtWI’s recent conversation with Givewell

DtWI had a recent conversation with Givewell60. In this conversation they gave a detailed update on their operation and we will highlight only a select few points that are relevant to their effectiveness.

In India, they plan to provide only “light-touch” technical assistance in some Indian states, where assistance would be focused on a more limited set of deworming components, based on state needs. This seems to be a very effective use of their resources, because DtWI would leverage governments to do the actual work themselves. Moreover, during the national deworming day they have assisted governments with media health campaigns (TV and radio spots about deworming), which we believe could be very effective (insert link to Development Media Initiative blog post).

In Ethiopia, DtWI reports that they have recently partnered with the Schistosomiasis Control Initiative (insert link) to provide technical assistance to the Ethiopian Federal Ministry of Health, which plans to implement a large scale deworming program. We think it’s a very good that DtWI continues to establish partnerships with excellent organisations such as Schistosomiasis Control Initiative and that they continue to expand into African countries, where Schistosomiasis is more prevalent.

In Vietnam, DtWI assists with an integrated deworming, hygiene education and sanitation program as well as the scientific evaluation of such programs. There seems to be a consensus in the scientific literature that Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) programs are needed in conjunction with deworming in order to slow down reinfection rates and that these programs are understudied.

This is in line with Givewell’s evaluation of the Deworm the World Initiative as a strong organization in terms of track record, evidence based self-evaluation, clear communication with independent evaluators such as Givewell, and high transparency61. Our main disappointment was their recent review of one of the DtWI Directors which we think treated the topic of malaria-STHs interactions, which could potentially be seen as problematic for DtWI’s operations, in a superficial manner.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Ben Kuhn, Gregory Lewis and some anonymous reviewers for valuable comments and edits on this manuscript.